Distilling the Lessons of a 100-Year-Old Family Business into a New Pursuit

I grew up working in our fifth-generation, Pacific Northwest-based family business. I spent my summers working on our legacy timberlands and for our beer and wine distributorship. During those early years, I recognized the importance of working hard and following your dreams.

After I graduated from college, I went to work for our beer and wine distribution business for a year before working for our investment company, managing our commercial real estate and timberlands portfolio. I have served in several additional roles for the family business, including board member for our investment company, family council chair, and, currently, as annual shareholder meeting chair. At the end of 2014, I made the decision to leave the family business. I was ready to venture out and create my own successes and failures and to build something myself. It was time.

In 2015, I partnered with my brother-in-law to start Pursuit Distilling Company. We are a 100 percent grain-to-glass distillery located in Enumclaw, Washington. We produce several brands of spirits, including Suspect flavored whiskey, vodka, gin, single malts, whiskey, and bourbon. We are currently distributed throughout Washington State and Oregon.

We’re a start-up company, and every day there’s a new mountain to climb, but our roots run deep. We are continually innovating and thinking creatively to differentiate our brand in this competitive marketplace. As we move ahead to leave our own legacy, our company reflects the lessons, values and long-term timeline I learned as a fourth-generation steward of a family business.

Hard Work

My great-grandfather was a pioneer in the timber industry. He was known to travel up and down the I-5 corridor visiting his current timber holdings and scouting out new timber tracks. He would pack sack lunches for the entire week on the road and would fill gas cans from his logging mill sites, storing the gas cans in the back of his car as he drove (safety priorities were clearly a bit different in those days). He was a frugal man and valued saving pennies where he could. His hard work, his pioneer spirit, and his work ethic have been the foundation of our family enterprise for almost 100 years.

That work ethic was ingrained early in our family, so I’ve never been afraid of hard work. That’s a good thing because there are no shortcuts in owning and operating a start-up company. I recently joked with someone that, in retrospect, the 50-60-hour work weeks I spent working for my family enterprise were a breeze compared to my current reality. Those days are gone. I work pretty much every day, and every day brings a new challenge. It’s a crazy ride, but I am excited and blessed to be on this road.

I currently manage marketing, sales, legal, distribution agreements, payroll, accounting, and, until recently, HR for Pursuit. I'm kind of the quarterback who just keeps the team moving down the field. Wearing a lot of hats has been a challenge, but growing up in the family business, I learned early the value of hard work. If there were a ditch-digging competition to see who could dig the most ditches in an hour or the entire day, I believe I would win. I just would never quit digging, and I would do it with a smile on my face.

Long-term Planning Horizons

We founded Pursuit Distilling with a 50-year business plan. I was 35 when we started the company, and I hope to be around at 85 knowing that my business will be, too. We’re in it for the long haul.

And it’s a good thing we are because distilling and aging spirits takes time and patience. Spirits have to sit in a barrel for at least four years to have any kind of credibility in the marketplace. That time in the barrel confers the Bottled-in-Bond designation, which can offer a rewarding payoff. For example, a 53-gallon New American Oak barrel of spirits costs us about $1k to produce. This cost includes the barrel, distillate inside the barrel, labor, glass, taxes, and a few other initial costs. After four years, that barrel—depending on quality and price point—is worth between $10k and $12k. So, patience is the key.

When you have a long-term investment horizon, you just know it will all work out. I always tell people, "Thank goodness I came from timber. Timber takes 50 years to mature and to get your return. If I can get a return back within 10 years that is a home run."

Stewardship

Though we’re a startup, we operate with a stewardship mentality. I tell our employees that everything we’re doing at Pursuit was made possible by my great-grandfather. His initial labor really provided our family the resources to allow me to go and do something that I love. It’s my responsibility to preserve that gift and carry it on to the next generation. I want my kids, who are young now, to have the opportunity to join this business—if they wish.

My ability to steward my own business relies on my connection to the key learnings of the family enterprise. I know the trove of wisdom that exists in our 100-years of business, and I capitalize on reaching out and connecting with my dad, my cousins, and my uncle for the good of my business, tapping them as resources to help navigate starting and owning the distillery.

These deep connections have been so rewarding as I forge my own path. My family members are my biggest cheerleaders. Their support is essential in the daily grind of startup life because there is no question that it’s easy to feel beaten down in the relentless pace of launching a new business. When a family member reaches out to me and is fired up because they’ve seen our product on a shelf somewhere, or because they have enjoyed a delicious cocktail from an establishment using our products, that brings a huge smile to my face.

Looking Back Encourages Me to Look Ahead

I know that all the lessons of the years I spent deeply involved in leading our family enterprise will continue to help shape my own business. It was a leap to step out on my own, but I did so from a very solid foundation.

My goal for Pursuit Distilling is lofty. I want Pursuit to be a world-class distillery, creating products that are shared around the world. It might sound crazy, but with a 50-year planning horizon, I’d like to think we can get there.

I also hope that Pursuit will continue to provide good jobs for people and making an impact in our communities for years to come. One thing I've always appreciated about coming from a family business is the honor that exists in taking care of families. We feel lucky to be able to provide our employees with a career and benefits, and we take that responsibility seriously. My hope is that in 50 years, I’ll be able to look out and see faces of people who have been with us for decades. That would be a dream.

I know it will take much more hard work to realize my hopes for our company, but that doesn’t scare me. I’m fueled by passion for this venture and by the deep sense of hospitality that really underlies this company. Sharing a great beverage, in my mind, is really about coming together, and I want everyone who enters our tasting rooms, drinks our products, or engages with us in any way, to feel that sense of hospitality that grounds us.

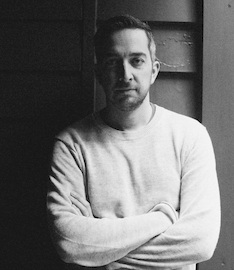

Sam Agnew is CEO and Owner of Pursuit Distilling Company.

Evergreen Teams Gather to Connect and Learn

Since 2013, Tugboat Institute has been providing opportunities for CEOs and Presidents of Evergreen® companies to come together to build trusted relationships, share best practices, and celebrate. Last week, we innovated that model by inviting members to immerse their leadership teams in the Tugboat experience.

The inaugural Tugboat Institute Gathering of Teams took place in Dallas, Texas over two-and-a-half days and brought to life the Evergreen 7Ps™ for attendees through “best-of” Tugboat Institute talks, workshops, and evening celebration.

As curators of this experience, our goal was to inspire, to create community across hundreds of Evergreen executives and team members, to share best practices, and to provide a deeper understanding of Evergreen values and practices. That sharing was evident on Tuesday evening, when attendees gathered for an opening experience led by artist Phil Hansen, who took the group through a drawing exercise that included connecting with other table members. From the outset, the openness and authenticity of everyone set the tone for the gathering and established early camaraderie.

After that festive evening, the talks on Wednesday provided insight into the Evergreen path and inspiration for continued commitment to Evergreen principles. Tugboat Institute Founder and CEO Dave Whorton led off with a deep dive into the contrast between the current venture capital Get-Big-Fast model and the Evergreen path, highlighting the long-term benefit of Evergreen values to employees, founders, customers, and communities. After Dave’s talk, seven members and thought leaders offered stories and best practices covering every one of the Evergreen 7Ps, while exemplifying the deeply held values and personal integrity that have come to define our community.

These authentic conversations were deepened through an afternoon workshop on Wednesday, which brought attendees together by functional role, moderated by experts with deep experience in each functional area. Participants in this session got to know one another, shared their own companies’ best practices, and had the opportunity to engage in an active Q&A session, led by the moderator. While many of those present had attended workshops and conferences around their functional role in the past, there was a strong sense expressed that this was different—that the content was more relevant and meaningful by the value-alignment among attendees and their companies.

As is the Tugboat Institute tradition, an evening celebration brought everyone together on Wednesday night. Attendees shared great food, drink, and company against the backdrop of exhibits in the Frontiers of Flight Museum, beneath the full-sized model of the Wright Flyer—an enduring symbol of Pragmatic Innovation.

On Thursday morning, an additional twelve members and thought leaders gave talks and participated in two panels. Our team was prepared to see the positive, energizing impact of these inspiring speakers and their messages—ranging from deeply personal learning journeys to tactical expertise—on attendees both Wednesday and Thursday morning. Despite that expectation, the reality of seeing attendees absorb the power and differentiation of the Evergreen path, many for the first time, far surpassed our hopes. It was incredibly gratifying to overhear the buzz of conversations about the speakers and observe new friends discussing the many topics.

The event concluded on Thursday afternoon with team workshops, in which our members gathered with their teammates and families to share their experiences and take-aways, reflect, and plan how to bring the best ideas into their own companies and lives.

We are incredibly grateful to members and teams who leaned into this inaugural event, diving into learning and new relationships with the generosity and wisdom that characterizes Evergreen leaders and companies. It was our honor to host those who are so clearly committed to growing thriving Evergreen businesses that will continue to provide benefit for employees, customers, suppliers, owners, families, communities, and the world on a long-term horizon. We look forward to continuing to grow this tribe and learn together.

Diana Price is Content Manager at Tugboat Institute.

Raising the Roof in the Housing Development Market

Our Evergreen® business, Roundhouse, develops and operates multi-family housing in four Western states. Historically, ours has been an extremely commoditized, financially driven industry. The goal for most developers in our space is to either provide a high volume of low-cost housing or—largely in coastal cities— high margin luxury developments. In both scenarios, most pursue short-term business plans that involve quickly selling projects upon completion in order to extract the highest-possible time-weighted return for investors.

We sit between the production developers and the luxury developers, focused on the middle market. We develop communities for residents who want a high-quality living experience. In our view this means a beautifully designed, healthy, environmentally sensitive environment that functionally improves their lives. Our approach to how we develop and manage our properties makes us an outlier in an industry built to serve investors first and residents second.

If you look at the websites of developers and investors—almost without exception—you’ll see numbers first: X-thousand apartments under management or X-billions of dollars of assets under management. The reason: they view their capital partners as their primary customers.

We think there's a better way—an approach that serves residents, the communities in which we build, and the environment while still producing a reasonable profit that allows us to grow and positively impact additional families.

We subscribe to the philosophy that when you make a good investment you should hold it forever. For that idea to be viable in our industry, our projects need to be durable, operate efficiently, and be timeliness in their identity. This standard requires that we spend more money upfront on materials and building systems that reduce the overall cost of operating and maintaining our buildings over a long period of time. This investment creates a durable stream of cash flows that can be reinvested into other successful projects. If we’re effective in our market selection in the face of trends such as climate change and urbanization, among others, the financial return will outpace our benchmark over time. It’s obvious to us that a long-term approach to investing produces a better result than short term profit-taking, and we’ve structured our business entirely around this concept.

Our long-term view is reflected in the choices that we make to construct high-quality, durable, environmentally sustainable buildings. An example would be the use of centralized boilers in our buildings. The additional up-front cost (in a hypothetical 200-unit apartment building) for this system versus installing individual water heaters may be $500,000 or more. If your business plan is to immediately sell the building upon completion, you would never incur this cost. But, if your business plan is to own the building for 30 years, you will save a multiple of that in energy costs and replacements. A single boiler may last for 30 years, whereas individual water heaters will need to be swapped out after 10 years (at which point we would potentially be dumping 200 water heaters in the local landfill.) This is just one of many choices we make that stems from our core values.

The second significant differentiator in our model is that we prioritize the resident as the primary customer and focus everything we do around providing them with a high-quality living experience. An important way in which we do so is by managing all property services ourselves. When we founded the company, we contracted with third parties to provide many services, but we found the service level provided did not equal the care and thoughtfulness that went into the development, design, and construction of the buildings. That was unacceptable to us, so we integrated property services into our core platform.

Now, we self-perform all maintenance, leasing, marketing, and resident retention. By integrating these services into our model, we ensure that every team member a resident comes into contact within our community is aligned with our values and our commitment to putting residents first. The quality of the service and the personal communication meets our company standards. Whether these are simple interactions with our maintenance staff or relationships that develop through community initiatives or events that we coordinate on behalf of the residents, the fact that we are managing the services of the properties that we build creates connection between our residents, our employees, and the cities and neighborhoods in which we build.

We also recognize that in order for our employees to serve residents in this way, we need to be equally committed to our team’s well-being. This commitment is another way we veer from industry norms. The property management industry has extremely high turnover because many of the jobs involve customer service and can be very demanding. As a result, employees are treated as expendable. We are attempting to flip that model by creating an environment that inspires our employees to come to work every day, aligned with the same mission that we pursue as developers and owners. Because we know that when our employees have a great experience, that positivity is passed along to the residents of the building and the wider community.

The design of our communities also reflects our commitment to putting residents’ quality of life first. For instance, one of our early projects, Blackbirds, in Los Angeles, connected 18 residences by way of a living street, which is based on the Dutch concept known as a "Woonerf." The area is meant to prioritize pedestrian uses over auto uses and includes beautifully landscaped community gathering spaces such as shared garden and resident mailboxes. The street created an open space for residents to play and gather, encouraging casual interaction and connection with neighbors and was a reflection one of our core values: belonging.

All of the innovations that set us apart in our industry reflect another of our core values—our Pioneering Spirit. This key driver compels us to continue to innovate, challenge the status quo, take risks, and identify emerging trends. When we do, we learn and grow to provide more for our customers—the current and future residents of our developments.

Casey Lynch is CEO and Co-Founder of Roundhouse.

Serving Dentists, Not Private Equity Investors

When I graduated from dental school in 1999, I operated a practice as an affiliate of a large dental support organization (DSO)—a company that provides business management and support to a network of dental practices. At the time, it was a relatively small, private company, driven by the entrepreneurial founder. His ambition and passion, combined with my love for dentistry, fueled my professional drive, and I soon grew the most productive and profitable practice in the organization.

As I developed my practice, the founder became a mentor to me, and I ultimately took on operational responsibilities for the DSO, becoming more involved in the corporate side of the business. My experience growing my own practice allowed me to contribute in meaningful ways to the development of patient-focused systems, trainings, and processes to support doctors, and it was really fulfilling. I loved that work and the company.

Unfortunately, I would see the inspiring culture, innovation, and profitability of that company incrementally eroded through a series of private equity (PE) transactions, which ultimately resulted in my decision to leave and found my own DSO, SOHDental, in 2017. As I grow my company, I am very aware of how my model for acquisition and management stands in contrast to the transactional and often contemptible practices of the PE approach. Here are a few key Evergreen® differentiators that drive my company.

Honor Company Culture and Founding Values

My goal when I acquire a new practice into SOHDental is to understand what that doctor is passionate about and then determine how we can support that passion on the administrative side so they can focus on patient care. Ideally, patients will never realize that there was a change in ownership. I want it to be seamless. We don't rebrand any of the offices, and we don't get between the patient and doctors. We believe that the doctors know their patients best.

My commitment to this approach was shaped by observing what can happen during a PE roll-up, when the goal of an acquisition is growth and economic gain. When you have recent business school graduates overseeing a dental office, conflict arises between their financially driven, metrics-based, transactional approach, where the focus is on quarterly budgets and sales earnings, and a practice culture of clinical excellence, lifetime patient care, and doctor-led philosophy. When management starts overriding what the doctors do while disregarding their passion and expertise, doctors are unhappy, patient care suffers, and culture is eroded. I saw this play out in hundreds of practices over my years in a PE-backed DSO.

Create Efficiency, Not Unnecessary Bureaucracy

When we acquire a practice, we understand that there are metrics and reporting that make sense to request to help a practice recognize what services their patients value, how they can improve communication, and steps they can take to serve patients better. We help develop processes and systems that can standardize the collection and reporting of this information. The goal of these efforts is to improve the quality of doctors’ time with their patients and the level of care provided.

What we don’t do is burden practices with becoming expert in financial reporting and enforce protocols and policies that force clinicians to spend undue time jumping through hoops. I saw what happens when private equity management demands layers of protocols and policies that allow them to centralize and scale. In my experience, the resulting bureaucracy and related documentation meant that doctors and administrative staff devoted hours to tracking and reporting that should have been spent on patient care and training.

The entire orientation of the DSO and the practice changes when the prescribed, common language becomes metrics. It’s no longer about relationships—between doctor and patient and between our operations team and the practices in our group. Instead, the verbiage is financial and transactional.

Better, Not Bigger

Every year, the DSO industry publishes a top-10 list of the biggest dental support organizations in the country. My former firm is always toward the top of that list. My goal: To never make that list. I don’t want to be the biggest—I want to be the best. For me, that means adding one doctor, one practice at a time. And because I don’t have private equity breathing down my neck, I can choose to grow when I know I have the systems and the people in place to deliver on my promise to that next practice to support them and their passion so they can focus on their patients.

And while the scale of these big organizations may seem impressive, I’ve seen the underbelly of that push to grow. I’ve seen the broken promise of management support that occurs when a practice is purchased to meet a quarterly growth goal without anybody on the operational side to actually support that practice for the next year or two. Because, from the PE perspective, it’s easier to buy 50 offices in a year than it is to train 50 good operational people to support those offices. This focus on growth at all costs, while it makes sense from an investment perspective, takes an incredible toll on the culture of each practice.

It’s also not a profitable model. When growth exceeds operational infrastructure and the practices don’t have the support they were promised, it stands to reason that there will be some practices that struggle. If it’s a very large DSO, there could be a significant number of failing practices. When that happens, the logical step would be to stop acquiring new businesses and focus time and resources on those that are struggling. But according to the PE world, just like in many industries, timing and perception is everything, the more and the bigger the offices in the organization, the more revenue the company generates. You go as fast as you can buying as many practices as you can, so that it looks like growth on paper when you sell it. And that’s okay because the PE partner will be gone in five years and the next PE owner will be dealing with the low-performing office. I saw that play out, and it wasn’t pretty.

Learning as I Go

My now 20 years in the DSO industry—first in a thriving, private organization and then through various versions of a PE-backed company—have taught me a lot of lessons about both the value and potential benefits of the service we offer and how this model can be twisted to erode the very practices we’re meant to serve. Having founded my own company, I’m looking forward to developing an Evergreen model in this space that is people-centric at its core. Because our business is really about relationships—between our support center and the practices we serve and between doctors and patients. I know we can build a group that is focused on these relationships and on supporting the office and team to truly make their jobs easier. My entire team knows this is our goal. Each time I buy a practice, I tell everybody in the support center: "It's not about you. It's about them and how we can support them."

Samson Liu is Founder and CEO of SOHDental.

Redefining Home Care with the Enterprise Model

I founded our Evergreen® company, Assistance Home Care, to provide families comfort in what for many is a very vulnerable time. Opening your door to home health care professionals and trusting strangers to step into your home and provide assistance can be difficult, but it’s an essential service for those who require in-home care.

My wife, Sally, was her mom's caregiver for five years while raising our three small children, and we saw how vital in-home care was for my mother-in-law. My father-in-law, who was in his eighties at the time, would have struggled to care for his wife without Sally’s help. As a very proud and private man, it also would have been very difficult for him to open his door to a stranger to provide the assistance he needed.

Having observed the reality of caregiving within our family, I was intrigued by the idea of creating a home care company that could offer someone like my father-in-law the assistance he needed with a level of comfort and trust that would allow him to open the door and receive help.

Beyond that family insight and my entrepreneurial drive to provide a solution for what I recognized as a significant challenge facing many families, I came to the home care industry with no prior experience. My prior twenty-year career was with Enterprise Holdings, moving up the ranks of the company to lead the truck rental division at corporate headquarters in St. Louis. So, while my experience in home health care was limited, I had learned valuable lessons in operating and leading in a purpose-driven Evergreen company. Key among those learnings was the essential philosophy upon which Jack Taylor founded Enterprise: “Take care of your customers and your employees first, and the profits will follow.”

It was with that simple, powerful foundation that I set about building Assistance Home Care. As I developed the business plan for the company, I recognized that there was an opportunity for Pragmatic Innovation in the industry that would help us serve customers and employees better. As we have grown our business, we have implemented several significant innovations that differentiate us and, I believe, have led to our success. These pillars of our company structure and values all reflect lessons and practices learned in my years at Enterprise.

Neighborhood Branch Locations

Most of our competitors in St. Louis have one location, from which they service the entire St. Louis area. We currently have four locations, with two more slated to open in the next six months, which will provide six locations in St. Louis, which is unheard of in the area.

Our branch structure reflects the Enterprise model, which was developed with the theory that if any one location got too busy, it would no longer provide the highest level of service. When one of our branches reaches this level, a new location is opened 15-30 minutes away, ensuring the high standard of customer care and, importantly, providing new leadership opportunities for employees to go out and grow great local relationships and serve more customers. Employees know that their hard work and their success allows for continued growth and that they benefit from their ability to grow the bottom line in this way.

My decision to develop branch locations allows us to serve as a community resource. Our customers and our referral partners view us as neighbors and recognize that we understand their unique community. It means a lot to a customer if their caregiver is local to their neighborhood—they feel a greater sense of comfort and familiarity, which improves their experience.

To respond to this preference, we recruit locally, and our branch structure serves as a billboard. We’re able to leverage the signage on our multiple locations, so potential employees and potential customers see our name every single day. That strategy allows us to remain top-of-mind, which is key because home care is something you don’t generally think about until there's an event that makes it necessary. When that happens, we want people to have us in mind.

The branch structure also allows us to support another key learning from my Enterprise years: If you don't have happy employees, you'll never have happy customers. The branch structure is a key factor in our ability to serve our employees. Recruiting locally means that our employees generally work within their own neighborhoods, so their commute time (and related stress and expenses) is limited and they are able to spend more time with their families.

Customer Experience First

We find that we spend time re-framing priorities for many of our Care Professionals (Care Pros as we call them) when they join our team. The reality is that many of our caregivers have previous experience in a nursing home environment or even a hospital environment, where they're serving anywhere from eight to 20 residents at one time. In this environment, they have been taught to accomplish set tasks on a set schedule, with the patient’s individual needs and preferences second. They're programmed to walk in that room, complete the task, and move on to the next patient.

We do things much differently. Our Care Pros are trained to put the client’s needs and preferences first. It’s not about sticking to a schedule for the sake of checking a box on a task sheet. We’re caring for human beings in their own homes, and they should feel comfortable and autonomous to the greatest extent possible, within the boundaries of safety, of course.

Our commitment to putting customers first serves as the gating factor in our Paced Growth strategy. We will only grow as fast as we can develop a qualified, expert care team to serve customers to our standards. We’re not interested in growing for growth’s sake. Our motivation to expand is to be able to provide additional hours of quality service because when we do that, we are serving people who need assistance and giving those hours back to the families who need that support.

A Clear Career Path for Employees

The Enterprise model of employee training and development offers a clear path to promotion and leadership. As I developed our business model, I integrated this approach. Each of our branches essentially has a manager, an assistant manager, and a management trainee. Management trainees are generally required to have a college degree and meet a variety of criteria that ensure they come to us with the skills and values we need on the team—and perhaps most important—a commitment to serve others. We also offer our Care Pros the opportunity to step into management through our Care Coordination Team, which places them in a leadership role managing other Care Pros, coordinating schedules, and managing relationships with our clients. We believe that committing to offer our employees this clear path for advancement helps us recruit the best talent and ensures we are always growing and learning as an organization.

Family Earns their Place

In my years working at Enterprise, I traveled frequently on behalf of the company, and I often found myself returning home to St. Louis on the final flight of the day, landing around 11 p.m. I still remember walking through the quiet airport late at night and seeing Chrissy Taylor, granddaughter of the company’s founder, sitting at the Enterprise rental counter in the airport, covering the late-night shift. Chrissy now serves as President and Chief Operating Officer of Enterprise Holdings, but she was not handed that position—she earned every promotion and reached up through the ranks from a humble beginning.

I have three children. My oldest graduated from college last year with a degree in health science. She interned in the office when she was in college, and when she graduated, she joined our company as a management trainee and has since been promoted to assistant manager. My older son, a senior in college, has also interned with us. I’m happy to have my children serve our company if that’s their choice. But they know that if they want to be successful in our company, they will have to work twice as hard as anybody else and demonstrate to the entire team that they're worthy of any advancement opportunities that become available.

As I look to the future, I am excited for the opportunity to continue to grow our company and serve more families. As I do, I continue to be grateful for my years at Enterprise. Enterprise always says that they will teach you how to run your own successful business, and, in my case, they did just that. I don’t think there’s a question that our company would not be as successful as we are, had I not learned so many key lessons from my time at Enterprise. Most important, still, that simple premise that if you take great care of your customers and your employees, the bottom line will take care of itself. That remains at the core of what I do every day.

Allen Serfas is President of Assistance Home Care.

Evergreen Companies are the Bright Lights of Capitalism

Dear Evergreen Journal readers,

Happy New Year!

Over the past year, there has been a growing call for companies to embrace the idea of running their businesses for all stakeholders, not just shareholders. In August, this idea was brought to the fore when the Business Roundtable announced a new Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation, signed by 181 CEOs who committed to lead their companies for the benefit of all stakeholders—customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and shareholders.

The new statement further fueled the discussion around the role of purpose in business and, more generally, of companies in society. While there is no shortage of examples of companies that take a mercenary approach to wealth generation and would benefit from a primer on purpose, I have to say that is not our experience at Tugboat Institute.

The Evergreen® businesses and leaders that comprise membership of Tugboat Institute adhere to a Purpose-driven, values-based definition of business success. Evergreen leaders believe in the power of People First. They trust that by being of service to their employees, their teams will, in turn, be of long-term service to their customers, their suppliers, and their communities, building companies that will add significant, long-term value and make a difference in the world.

In 2019, we had the opportunity to visit five Evergreen exemplars, members of our tribe who generously opened their companies to their Tugboat peers to share best practices and connect. Our visits to Radio Flyer in Chicago last spring and to Balsam Brands, SmugMug + Flickr, The Bi-Rite Family of Businesses, and the San Francisco 49ers in Silicon Valley last fall once again confirmed what I have been learning over the past eight years about these extraordinary Evergreen companies and their leaders—and the contrast they represent to mainstream business commentary.

These are companies that care deeply about their employees, investing in training and development, rewarding them fairly, and striving to ensure a comfortable retirement that doesn’t require winning the stock option lottery or a second job late in life. They are actively involved in intentionally creating good jobs in their local areas, bettering their communities, and supporting impactful philanthropic efforts.

Rather than being run for the benefit of the shareholders’ bank accounts, Evergreen companies are being operated for the benefit of the shareholders’ values. Often, in an Evergreen company, the CEO is also the owner, or, in some cases, the owners are a small group of individuals and employees. Ownership is not represented by a hypothetical, blank-faced group of hedge fund professionals, day traders, or racks of robot computers running trading algorithms, moving in and out of ownership at a drop of a hat.

In Evergreen companies, managers make decisions that reflect the owner’s values. This can mean foregoing distributions of profits/dividends to protect the company in a downturn, investing in long-term projects, letting the business slow down to absorb recent growth, and avoiding knee-jerk layoffs to meet quarterly projections—all things that the majority of public company investors have little tolerance for or consider lack of managerial discipline. Facing a penny-a-share-miss, even the best public companies are tempted to lay people off to “make the quarter,” potentially harming the company’s culture and employee trust for years and years. Unbelievable but true.

Evergreen leaders also understand that while not their purpose, profit is the most-accurate measure of customer value delivered, the fuel of future growth, and the protector of company viability and survival. Many owners of Evergreen companies share a portion of the company’s profits with their employees through a number of creative profit sharing plans, share a portion with our government through taxes, use some to pay down debt (if they have any), and reinvest the remainder back into growth and Pragmatic Innovation projects that will fuel the company’s continued relevance to customers and its future success. And, some Evergreen companies allocate a specified share of annual profits to charitable causes.

For many, the Evergreen mindset leads owners to defer personal financial gratification for a long time—in some cases, beyond their lifetimes. Why? Because their Purpose and their people are more important than a yacht, a private jet, or a mansion. These leaders want to see their companies and their values survive and thrive for a hundred years or more. That said, if the byproduct of being a great Evergreen company is significant wealth generation for the owners, then that hard-earned financial success is something to celebrate, and, ideally, a motivation for other entrepreneurs to take the Evergreen path.

For all of these reasons, I continue to believe that Evergreen companies represent capitalism at its best and deserve greater appreciation and recognition. Knowing what I know about Evergreen leaders, I look ahead to 2020 with optimism and enthusiasm, regardless of what happens in our capital markets.

I hope you will continue to read Evergreen Journal each week to meet these leaders and companies and learn from their experiences. May the positive example of business that they represent serve to inspire you and provide a welcome, alternative perspective on business success in the year ahead.

With Gratitude,

Dave Whorton

Founder & CEO, Tugboat Institute

Just Do It. Sit There.

As Evergreen leaders, I would guess that many of us set pretty high expectations for ourselves—in business and in our personal lives. I know I do – often to the point of being harder on myself than is productive. I am generally trying to get a lot done and, justified or not, I often feel like I need to do more just to keep up.

I was introduced to meditation in college by a happenstance flyer advertising a lecture by a visiting Japanese monk. I decided to give it a try. Since that time, I have found that meditation offers a way to practice pausing just a moment more before saying or doing the next thing. At my best, I can experience some of my thoughts and emotions without letting them immediately drive my actions. My goal is to meditate each workday, and the practice continues to help me find clarity and reduce stress.

While it may seem counterintuitive (meditation sounds like a something that happens very much in your head) the practice allows me to focus on acting and doing rather than ruminating. My practice is most informed by the Japanese Zen approach to mediation, which in my understanding is focused on paying attention to my breath and my body (rather than on a mantra or a visualization, for instance). I have found that this seemingly simple commitment to sitting for a few moments each morning before I go to work –just breathing in and out—is a ritual that positively informs my day.

As a side note, I don’t consider myself a Buddhist. I don’t find a conflict between this practice and my religious beliefs. Rather, I view it as a tool that enhances the way I approach life more generally, including my own religion.

In my personal practice, I sit first thing in the morning, before I look at my phone or do any type of work. While I would ideally sit for twenty minutes or more, often that is just not possible given the varied demands of a job and a family and perhaps a late wake-up or two. The commitment I’ve made to myself is that I will sit every workday for at least one minute. Often, I sit for more, but every day I know I can find at least sixty seconds. For me, this acts as a kind of placeholder, and it has helped me stay committed to the routine. Sitting on a meditation cushion, or some days just on the edge of the bed, I count my breaths, breathing evenly in and out ten times. Then I repeat. Most days I set a timer, some days it’s just 10 breaths (one minute) and I need to go. That’s it. It’s just sitting, breathing in and out, and doing my best to observe what's happening as I do that.

Many people think they are not good at meditation because their thoughts wander. The truth is, everyone’s thoughts wander—it’s just what thoughts do. The question is, when you notice that you are thinking about that upcoming meeting or the way you spoke to your employee yesterday, can you make the choice to let that thought rest, and bring your attention back to your breath or your body? Even if just for a moment. The thoughts will come again—they always do. It’s primarily a matter of returning when you notice.

While the focus on breath may seem a lesson in concentration and focus, the gift, for me, is the practice in letting the thoughts go. I think most of us operate in this almost ceaseless chain of thoughts and reaction, but if we can practice letting those thought-chains rest before we take action, perhaps that action can be more proactive and more intentional.

Though I’m not always aware when it happens, I know that this practice is translated into my workday. For instance, I may have an interaction with someone who says something that makes me feel an emotion and triggers a chain of thoughts, which, in turn, trigger a reaction. If I am able to observe and recognize that process and intentionally drop that chain of thoughts, I have created a bit of space to gain perspective. I can step back, for just a moment, and recognize the pattern. Instead of reacting, I can gain control of those thoughts. I can manage them instead of letting them manage me.

As a leader in my company, I think this ability to pause and take intentional action is a benefit. We can all get caught up in the frenetic pace of our roles—responding to emails and customers and internal issues—and can find ourselves surfing the wave of reactivity. To the extent that meditation can help me notice thoughts, sit with them, and avoid reacting, it can be a powerful tool. If someone comes into my office with a fire to put out, maybe I’m a little less likely to catch that fire. Instead of reacting right away to put it out, I might be able to wait a beat and then empower that person to put it out themselves. Note that this is not about sitting back and doing nothing. Rather, it’s about accessing the clarity to intentionally make effective decisions. I believe it allows for a more agile approach to the demands of business.

If you are interested in the science and psychology behind meditation from a Western point of view, I recommend Why Buddhism is True by Robert Wright. If you are interested in the Eastern, spiritual basis of this practice, I suggest Zen Mind Beginner Mind, by Shunryu Suzuki. Like many mind-body practices, meditation can be a tool to help you engage more effectively as a leader and provide you space for reflection. It’s not a panacea, but, in my life, the simple act of sitting still and breathing in and out continues to offer welcome benefit.

Ari Blum is President of Catalyst Real Estate.

One of the Best Restaurants in the World Puts People First

My grandfather, who founded Canlis, the 70-year-old fine-dining restaurant my brother and I now lead in Seattle, was known to wear a cape. And a lot of jewelry. He was an egomaniac who ran the restaurant much in the model of celebrity chefs that pop-culture has elevated today. He was a rabid perfectionist. He would have made for great reality television, our grandfather. Eccentricities and ego aside, his drive and innovations in fine dining built a restaurant that came to be recognized as one of the best in the world.

My parents, who took over the company in 1977, ran it with a different set of values. They cared less about ego and perfection and instead prioritized hospitality and family, community and philanthropy. They wanted everyone to feel welcome. Their approach guided the restaurant for 30 years, building on the reputation my grandfather established, garnering awards, and maintaining the restaurant’s place among the finest restaurants in the world.

It’s that restaurant that my brother, Mark, and I grew up in. It was a fine-dining, gorgeous restaurant that was all about people.

When my brother and I stepped in to lead Canlis in 2007, we did so against the backdrop of a rapid evolution in fine dining. Propelled by the advent and popularity of food television, chefs had become celebrities, and food and restaurant culture had become a pop culture phenomenon. Central to that culture was the image of the shouting, screaming, egotistical chef that my grandfather epitomized. The drama made for must-watch television, and the story that began to be told about fine dining kitchens was that they were toxic places of abuse, unfairness, and neglect. And the reality was, some great kitchens were run in this way. And often it was those great kitchens that got a lot of attention.

This was the landscape Mark and I entered as third-generation stewards of the family business. We knew that we needed to evolve the restaurant to compete in this new era of increasingly educated diners and elevated food culture, or we wouldn't survive. We had a decision to make: were we going to follow the model of other world-class restaurants that generally put product before culture, often fueling this negative, destructive culture that was being glorified? Or, were we going to try to be something else?

We had the benefit of the two models that came before us: our grandfather’s and our parents’. When we put our heads together, the question we asked was: "What if we could do both?" We didn't have a model for that among the world's great restaurants. We had not met a restaurant that shared our vision: to become one of the best restaurants in the world not in spite of caring for people but because we cared for people. We set out to forge the path.

Twelve years later, as we enter our seventieth year, we’re a happy anomaly. We are a thriving third-generation business, a restaurant that has defied the odds in longevity, and we believe the reason is our decision to take the best of both generations and create a new model for restaurant culture.

Our mission: To inspire all people to turn toward one another. That's an unusual mission statement for a fine dining restaurant. But we have lofty goals.

We want to help guide the industry, and in turn businesses across the country, to realize that caring about people is not a weakness. In fact, we believe that caring about people is a competitive advantage. That's the strategy we feel will allow us to become the best restaurant in America. And that's exciting for us because if we become the best, people will care about what we have to say. People will look to our model as they build their own businesses.

We have built several significant pillars to support our model, allowing us to bring together a value-aligned team, educate and empower that team to support our goal of being the best restaurant, and, ultimately, help transform restaurant culture.

Building a Value-Aligned Team

We ask people one question in our interview: “How will working at Canlis help you become who you want to become? Not what you want to become, but who.” The question surprises people. They're ready for us to grill them on their experience and their knowledge. But we believe the only person who really knows if this is the right job and if they will be the right fit for Canlis, is the person themselves. After the initial interview, we ask them to come work a shift at the restaurant, and they see how hard it is. After their shift, we sit down with them, and we say, "Now you know who we are. You've seen how it works. Are you the right person for the job?” We ask them to go home and talk to their partner or their kids or their parents, to consider if this job fits their vision for their life and to make a good decision. After that, only about 25 percent of applicants come back and say, “I want this job.”

The result: we build a phenomenal team of people with an aligned mission, direction, and purpose who really care about what we're doing. They understand the intensity of the work, and they still choose it and us.

Investing and Educating

We have 120 employees right now, and our hope is that every one of them leaves Canlis with a degree in running a business differently. All of our middle managers go through a year-long program we call Canlis University, designed to essentially offer a graduate degree in Canlis' management style. We teach them how to read a P&L, how to write a business plan, and how to create a mission statement—all tools they can use with us and in a future job.

Why invest in educating current employees for their next job? We know our employees are not going to stay here forever. We want to prepare them for the rest of their career. We know that if we do this, two things happen: first, when employees understand our investment in them today, they are inspired to give so much more; second, if and when they move on, they will bring our People First approach to the next restaurant they step into and help transform restaurant industry culture. It’s win-win.

Celebrating the Exit

When we hire an employee, we say, "We want to be a part of your exit.” People are often shocked by this. In the restaurant industry, there's a culture of betrayal if you leave and go work somewhere else, and there are a lot of burnt bridges as result. We think that’s unnecessary.

If Canlis is no longer the place that's helping a person become who he or she wants to be (again, who, not what), that person is no longer the right fit for our team. When that happens, we want to work together to find the perfect place for that person to land. We have an incredible network of connections in the industry, and we want to help deliver the employee to the next best place. We love the process of serving people in this way. And, when that person finds the next place, we throw a party to celebrate. We treat it like graduation day, and we hope he or she will carry the culture and lessons of their time with us forward.

What we’ve discovered as we’ve embraced this approach is that when we're investing in how people leave our restaurant they actually stay longer and they're more committed when they’re here. In addition, we’ve created an incredible alumni network of people who love our culture and believe in what we do. We are building bridges rather than burning them, and we are sharing that positive culture with the wider restaurant world.

The Big Picture

I sincerely believe that choosing to run Canlis the way we have, by putting People First, promotes longevity, provides a competitive advantage, and makes it a hell of a lot more fun to go to work in the morning.

On a larger scale, we believe the work we are doing in our own business can help improve our industry. There is a lot that’s broken in restaurant culture today. Food industry employees suffer from some of the highest rates of addiction, depression, and suicide. The irony is that we're supposed to be an industry that fills people up. The word restaurant comes from the Latin word for restoration. People come to our restaurants to be restored. And yet, we ourselves are the ones in most need of restoring as an industry. There's a sadness in that, and we want to help change that reality.

Ultimately, the magic of the dining room table is that it brings people together. It puts us across from one another, and it forces us to be eye-to-eye. There’s magic in breaking bread and drinking wine together and in what can happen relationally at a table. We all know how special that moment can be. We are grateful to play in some small part in turning people toward one another—at the table and in our business.

Brian Canlis is President and co-owner of Canlis.

Virtual (Assistant) Breakthrough

Toward the end of 2018, I hit a breaking point. Sales at our Evergreen® business, Life’s Abundance, were up about 20 percent over the previous year, and our profit was at an all-time high. But I was in big trouble.

Since joining the company in an IT role in 1999, I had consistently reinvented systems for managing my time as I took on new responsibilities and the demands on my time increased. I had done all the standard things to cope—I had delegated responsibilities; I had someone managing my calendar; I had a travel agent booking my travel; I had project managers handling many key initiatives in the company. Now, though, I found that I didn’t have any more tricks left up my sleeve to free up the time I needed to continue to manage the company in the way I knew I should into the future. Something had to give.

It was at this point that I had a conversation with a friend that changed everything. I had been describing to him that email was killing me. I had 900 emails in my inbox. I was drowning. His response: "You need a virtual assistant." He described the role to me—a professional who works remotely to deliver administrative support, handling a wide range of personal and work-related tasks online, including email management.

It hadn’t occurred to me that I might actually be at the point where I needed to hire someone to take over my email. That had always felt too sensitive, and I couldn’t imagine how someone else would be able to prioritize and filter for me. But I was ready to try anything.

So, inspired by desperation, I began to look into virtual assistant services. My search led me to a company that matches executives, exclusively, with virtual assistants. When I asked about email, they said, “of course we can manage that for you.” I was in—almost. First, I had to justify making the investment. I think, as business owners and leaders, sometimes the last person we invest in is ourselves. But, as I considered the other services that I was willing to spend money on, I realized this investment was as least as important.

I said yes to the possibility of time, and I entered into a matching process that included extensive interviews covering my management style, my personality type, and the scope of work required. I was informed that the assistant had also been thoroughly vetted—extensive background checks, professional references, and personality evaluations had already been conducted to ensure she was highly qualified and could be trusted to manage the most sensitive professional and personal information. The rigorous process resulted in a perfect match. I felt comfortable and aligned with my assistant, Jennifer, from the beginning.

I realized quickly how essential that sense of comfort and trust was because, once matched, the next step required a significant leap of faith. I had to provide my credit card numbers, my driver's license number, my social security number, my passport information, my global traveler information, and login information for all of the websites that she would need to access—and I had to provide the same for information for my wife and my son.

I know. It was scary. But the reality is that if I really wanted someone to manage tasks that were robbing me of valuable hours, I had to provide the tools for her to do that. I also gave her access to my personal and work email.

Over the next 30 days, working 20 hours per week, Jennifer reviewed all of my emails, and, through communication with me as she did so, was able to understand a lot about me and about the company to begin to filter and respond to mail. During days 31 to day 90, we focused in on more nuanced work style and preferences—she learned how much time I like between meetings and my communication style, among other topics. By the end of 90 days she was truly functioning as an extension of me: she was proactively managing my work and personal email and calendars, booking all travel, and managing personal projects like home repairs.

I realized just how much Jennifer had transformed my life during a work trip at about this time. Up to that point, getting on a plane meant I automatically turned to email with the goal of knocking out a few hours of work during the flight. This time, I turned on my computer and stopped: I had no email to respond to. It was like the first day of summer vacation: I felt like I should have homework to do, but instead I had free time. It was an incredible.

And while the email management is a huge piece of what makes this service so valuable, I think that the real differentiator in this investment is that because of her extensive experiences assisting C-level executives, Jennifer is qualified to be an extension of me. For instance, if I have a product idea and I want to research, what might take me one to two hours of online time just getting to the sources and filtering the background, I can turn that task over to Jennifer, who does the research and creates an executive summary that takes me five minutes to read.

My onsite assistant continues to provide me administrative support at our office—handling professional tasks that require an in-person presence onsite. The two positions complement one another and are clearly defined. This dynamic provides an important buffer between staff and sensitive information, protecting my onsite assistant from the burden of knowledge and ultimately having to be an island. A virtual assistant is entirely unencumbered by office politics.

As leaders of Evergreen companies, our time is the most important asset. Investing in someone who can help us optimize that asset just makes sense. If I had any doubt about the impact of hiring Jennifer, a recent conversation with my marketing director confirmed that I had made the right choice. She said to me, "I don't know if you realize this, Lester, but Jennifer has really been a game-changer for me. You have no idea what life was like the couple of months before she came on board. You were so overwhelmed, and we couldn't get stuff done. Now, I don't have to think about how I’m going to track you down if I need an answer because I get a response immediately from you or from Jennifer, and the company is able to move along a lot faster. We feel like we have our leader back."

Her comment hit home because I know she’s right: this gift of time and efficiency has also allowed me to lead again—to focus on larger, more strategic goals. As an example of this, I have a couple of new products that I had been wanting to launch for a couple of years, and I just couldn't find time to move these projects forward. I was actually able to hand the projects off to Jennifer and say, "Can you get this kick started for me?" Now we're going to have two new products come to market in the next six months that would have still been on the shelf if she wasn't around.

The benefit to my work life and my business continues to grow, but the fact that she handles both personal and professional projects is the real hack—the thing that buys the time back. Being able to off-load personal tasks has allowed me spend time on what matters—at home and at work. If I spend two hours communicating with a power-washing service to take care of my roof, that’s two hours I don’t have to focus on my business or spend quality time with my family. There is no reason for me to be devoting time to that task, which someone else can handle from start to finish. And our lives are filled with tasks like that, tedious but necessary.

At the end of the day, the biggest benefit to me is that I feel re-energized and unburdened. I didn't realize how much pressure I was under until some of that stuff was lifted off of me. I am able to be a lot more visionary. I don't get bogged down with stuff like I used to, and nothing falls through the cracks. My team has their leader back.

Lester Thornhill is CEO of Life’s Abundance.

Constructing a Foundation of Trust

The foundation of our Evergreen® company, cookline, is trust. It is the most essential ingredient in our success, and the thing that sets us apart in our industry. We are general contractors devoted solely to building restaurants in the San Francisco area, working with restaurateurs to create high-quality, beautiful spaces that reflect their vision and provide the greatest opportunity for success in a notoriously tough industry and city.

An unconventional upbringing and path brought me here. In 1971, my parents joined a group of about 300 like-minded people living in San Francisco who had a dream of living off the land and building a community on shared values of non-violence and respect for the environment. I was born on a commune in Tennessee and lived there until I reversed my parents’ steps and moved West to California after I graduated from high school.

The pillars of the commune were trust and food—we lived sustainably on the land, growing our own food and trading with local farmers for other goods. Nobody used money. The success of the community was completely dependent on members helping one another.

Many of my most vibrant childhood memories revolve around food—eating my mother’s bread fresh from the oven after school, hours spent cleaning and preserving strawberries received in trade from our Amish neighbors, learning to cook and making meals for friends and family.

I absorbed and embraced a respect for and joy in food and in the community that sharing food creates.

This early connection to food and community led me to restaurant work in California at age 19. Over the next 10 years, I worked my way up through the ranks of restaurant management, beginning with an entry-level kitchen position at San Francisco’s iconic Boulevard and ultimately serving as project manager for bakery chain La Boulangerie, as that business expanded rapidly throughout the Bay Area.

Those years taught me many lessons in Perseverance and essential management skills. I was fueled through those often-grueling days by my love for the tight-knit restaurant community in San Francisco. Here was a community—like the one that had raised me—that was focused on food, trust, and perseverance, and where people helped one another and supported each other’s businesses and their neighborhoods. Finding my place in that community was a homecoming.

From my early years in the restaurant industry, I had a clear sense that I wanted to have my own business. At first, my dream was to open a restaurant, but when I was appointed Project Manager at La Boulangerie and worked closely with the general contractor hired to build out new locations, I saw the opportunity for a different path.

Observing the manner in which the contractor conducted business with his clients—all restaurants—revealed a disturbing lack of trust and transparency in those relationships. I was blatantly lied to during my time managing the La Boulangerie project, and the lack of customer service generally was non-existent. The contractor’s single priority was his bottom line, and the customer’s needs and budget were often ignored. Change order fees were huge, and job costs were routinely 20-30 percent higher than the initial bid. There was a complete lack of understanding of the razor-thin margins with which restaurants operate and the precarious financial position of these businesses in such a competitive market.

I knew then that I could create a different, better model of a general contracting business that would serve the unique needs of the restaurant community. I knew that restaurants count pennies to make it, and the failure rate is staggeringly high. I wanted restaurateurs to have every opportunity for success, and I wanted the unique trust that exists within the San Francisco restaurateur community to extend to the contractor charged with building their businesses. I wanted to create a new relationship model. This was something that I could do—and do well.

With this goal in mind, I spent two years working for a general contractor to learn as much as I could about the construction field. In those two years I further experienced the frustration and the financial cost of this ongoing misalignment and tension between contractor and restaurateur. I also observed the fact that the contractor I was working for, a man who was building a company around the restaurant construction, did not actually eat at the restaurants he built. He didn’t support the community from which he made his living.

In 2014, I co-founded cookline to offer a different approach, to serve the restaurant community I love so much and understand well. I wanted to not only help the restaurateurs create the spaces they envisioned, but I was also committed to establishing relationships built on trust and integrating myself into the community of clients I served.

Today, we focus every day on being transparent and honest with our clients—and saving them money—while delivering quality workmanship. We strive to value engineer and follow through to the end to create a positive relationship with the client. We watch out for our clients’ bottom lines by collaborating with designers and subcontractors throughout the construction process, seeking out lower- cost alternate materials, suggesting design changes that will be less expensive, and always focusing on the schedule to find efficiencies. The result of this hyper-focus on client experience and cost has allowed us to give money back to every single client.

Through these commitments, we have developed trust in an industry more commonly committed to their own profit. When our clients open a new restaurant feeling great about the space and without an undue financial burden, we hope we are offering them the best opportunity for success. That matters to us.

But our commitment to the restaurant community goes a bit further. Our engagement with the restaurants we build does not end when we hand over the keys to the space. We eat at our clients’ establishments; we purchase gift certificates for our employees so that they can also dine at the businesses they help bring to life; our weekly company happy hours are catered by our clients. I’ve attended a client’s wedding and have developed meaningful, lasting friendships with people who were my clients first.

In my mind, as I dreamt of creating a business in the restaurant industry, the goal was always to make a difference in the tight-knit community that I loved. Now, as I strive to transform the relationships and services in our niche of restaurant construction, I feel I’m doing just that. Our clients feed our community, and we are able to help them deliver that magic of a shared meal, and hopefully given them a better chance of long-term success based upon our quality work.

I wouldn’t be where I am today had my path not started where it did or travelled the unconventional route it took. I feel that I have now come full circle—from my childhood on the commune, where trust and food were the focus of our lives, I am now building restaurants that are the heart of their communities.

Levi Hunt is Co-Founder of cookline.