How Anthropology Can Help Evergreen Executives

Anthropology looks at how we went from an agrarian society to an industrial society to what is rapidly becoming a technological society. We look at these changes by getting up close and personal with specific groups, or “cultures.” Traditionally anthropologists studied indigenous peoples, but today they often focus on contemporary communities.

One culture to which you and I both belong: the community of businesspeople.

I didn’t study anthropology because I wanted to be better at business. I studied anthropology because I wanted to get a deeper understanding of how human beings interact and how they deal with change.

When I decided (after getting my Ph.D. in anthropology from Columbia University) to go into law, I thought that I would eventually view anthropology as a diversion from my true professional path. But what I found was that at every turn, from practicing law at a firm, to serving as general counsel at McCaw Cellular Communications Inc. and Netscape Communications Corp., to developing interdisciplinary study programs at Stanford University, I was always looking at my work through an anthropologic lens.

That’s because the questions we ask in anthropology are the same questions leaders need to ask themselves in order to build excellent, sustainable organizations. What are the different values people are bringing to this group? What is our group culture? And how can these people find new ways to work together in an ever-changing world?

Evergreen executives will recognize this as a People First mentality. If you’re Evergreen, chances are you’re already thinking about your people a lot and you already realize that their success is your success. But viewing your company as an (honorary) anthropologist will help you get an even deeper understanding of your organization and how you can make it even stronger. Here are three ways you can do so:

Encourage Flexibility

Society and institutions are always evolving. Look at the long history of human development. We’ve gone from living in isolated tribes and farming villages to being a constantly connected global community.

That’s big-scale change, but this kind of evolution is also happening on a more intimate level. Demand for a company’s product grows and subsides. A new deal requires internal growth. Or expansion into new markets means the company has to rethink who is responsible for what.

Understanding and accepting that everything is in flux is an important part of what makes societies succeed, and it’s crucial for businesses, as well. Never assume status quo, and make sure your people adopt a similar mentality. By encouraging flexibility, your organization will be able to grow and change more easily.

Focus On Your Company’s Values

Individuals have values, but so do institutions. Stanford, for example, values learning and giving back to society. Those two elements have to be part of everything our university does, and we need to impart these values to our students.

On a societal level, cultures are defined in part by the similar values held by their members. Businesses work slightly differently. An Evergreen CEO needs to know their company’s values, use them to support and protect their corporate culture and then make sure to hire people who are comfortable with these values.

It’s crucial that you understand and clearly articulate these values. What do you stand for? What’s the bigger purpose of your organization beyond making money?

Having strong values and a strong culture is even more important for Evergreen companies that want to survive for 100 years or more. The values you put in place today can help to keep the company leadership focused through successive generations.

Put Humans First

It might sound obvious to say that humans are at the center of every business, but as technology evolves, that’s no longer a given. I worry quite a bit that we’re not focused enough on people right now in our endless quest for efficiency. Automation might be good for the bottom line, but it isn’t always good for your organization.

That’s not to say that you shouldn’t use technology to improve your business. But leaders need to keep their people front and center as their companies evolve. Humans are the ones who are going to make your vision a reality, no matter how many robots or how much artificial intelligence you use. Making sure that those humans are comfortable with any change and that they know they are still valued is crucial for today’s organizations.

Evergreen companies are not immune to these changes. But with their People First outlook, they may be able to weather this evolution better than public companies that are so focused on the bottom line.

Taking the lessons of anthropology — putting humans first, understanding that everything changes and keeping your company’s focus on its values — will go a long way toward helping you build a sustainable business.

How Our Biggest Crisis Brought Our Company Together Again

In the franchise business, trust and respect are paramount. If your franchisees stop trusting you, they’ll stop caring for their customers, and the business risks falling apart.

This is something we’ve always known at Taco John’s, the 382-restaurant franchise where I am now president. But in 2013, we became dangerously distracted by profits and sales and almost lost that connection to our franchisees that, for me, has always made Taco John’s so special.

James Woodson and Harold W. Holmes franchised their Midwestern-based Mexican fast-food eatery in 1969. Many franchising companies own a majority of their restaurants, but we have only 10 company restaurants; the rest are all franchisees. I started here in 2000 as the director of technology.

In 2013, in an attempt to boost sales and grow the number of restaurants, we brought in a new CEO who applied a strict profit-focused strategy. While we didn’t see it at the time, this turned out to be a serious mistake.

Rather than consulting the franchisees and getting their buy-in as we always had, we started making changes straight from the top. We removed items from the menu, even when those items made up 8% of a restaurant’s annual sales. We dismissed our franchisee operations committee. We changed worktables from steam to dry heat, which was devastating to owners who love their old equipment. And we pushed franchisees to buy precooked taco meat rather than make it themselves—at an annual profit loss of $15,000 per restaurant.

By 2016, more and more of the franchisees were disillusioned and almost combative. We dropped from 405 to 382. We lost 57 employees from our Cheyenne, Wyoming, headquarters from 2013 to 2016. As a company, we felt we had been violently shaken. Our culture was in tatters. We realized we had to get back to our roots and that meant that as a company, we had come together.

I took over as president and chief executive officer in August 2016 and made it my goal to get back to our corporate culture of being more collaborative with our franchisees. I was lucky enough that our former head of human resources, who had 30 years of experience with the company, came back to help us regroup. Any time there’s a big change at the top, employees panic that they are going to be the next to go. She met with people and put an open-door policy in place to make sure that our 70 corporate employees felt safe and cared for and ready to work more closely with our franchisees.

Our vice president of finance and in-house general counsel stepped in to help keep the day-to-day business of our corporate headquarters going while I hit the road to visit, in person, as many of our franchisees as I could. I wanted to reassure them that we were once again going to be a company that listened to them and took their needs into consideration.

Our leadership team worked hard to reconstitute our committee system, which had always been the heart of Taco John’s culture but had broken down over a growing “us vs. them” mentality. Our committees are made up mostly of franchisees managers with our corporate personnel providing leadership. The committees make important decisions about matters such as menu changes, advertising and who will supply our restaurants. We made sure we had the right people on each committee to foster an atmosphere of cooperation.

We are also now planning to meet twice per year with the Association of Taco John’s Franchisees Board to ensure that we are all in alignment on brand priorities.

The effort is starting to pay off. A few weeks ago we had our annual national convention. I took the time to write every franchisee a hand-written invitation, and as a result, we had more people attending than for any conference in the last five years. For the first time in a long time, it felt like we were a family, who trusted one another again.

In his opening remarks, our franchisee association president said: “A new era of trust and cooperation has begun. We have a new leader who is working to rebuild relationships with shared ideas and a respect for the franchisees.” That’s more than I could have hoped for.

We are now at 382 franchises and expect to be back to 405 by the end of this year. Our team effort is paying off.

Jim Creel is the President & CEO of Taco John's International, Inc.

Why I Tell Students They Should Consider Family-Owned Businesses

Family businesses are, by their very nature, quiet. They don’t have to report on their financials, they tend not to promote themselves to investors, and any press can often mean unwanted attention on family dynamics.

So it’s not a huge surprise that most of the students I encounter through the business school at Loyola University aren’t thinking about family businesses as they assess their post-graduate job options. But as I like to tell them, if they don’t think about opportunities at family businesses, they’re shutting themselves off from what could be a very satisfying career.

I had my aha moment on family businesses around 2008. At the time, I was working at an outplacement company coaching C-suite executives who were looking for new jobs. In the wake of the financial collapse, many smart, talented people had been let go simply because their corporations needed to cut their budgets by 10 percent. These people hadn’t been let go for cause; they had been let go for purely financial reasons.

At the same time, I was consulting at the Family Business Center at the Quinlan School of Business at Loyola University in Chicago, where I am now the director. I was facilitating small groups of leaders from family-run businesses who were coming together for support and to learn from each other.

These executives were facing the same economic challenges as the big corporations that were laying off C-suite executives. But they were dealing with them very differently. They were being creative and purposeful about finding ways to retain their employees. They weren’t worried about their debt because they didn’t usually have much. They weren’t just thinking of themselves and their bottom line; they were thinking about what would be best for their entire work community.

I saw that family-run businesses have a different set of values, and that attracted me. I decided I wanted to work with people who are trying to create lasting value in their businesses and their communities.

There’s a lot of overlap between family-owned businesses and Evergreen companies, many of which are family-run today, or eventually family-run after the first generation. Both groups tend to put People First — paying as much attention to the growth and well-being of their employees and customers as they do to their Profits. Both groups tend to avoid outside investments and debt. And companies in both groups tend to have a deeply held Purpose that serves as their north star.

Twice a year I go into the classroom to make my pitch for family-run businesses. Here are the advantages I lay out for the graduate students:

A Bigger Mission

Millennials are children of the recession. They’ve learned that work needs to be about more than a paycheck — that it needs to be satisfying in a deeper way. So they’re looking for mission-based companies. Family-run businesses often fall into this category. Many family businesses that have been around for several generations have kept the company (and the family) together by having everyone focused on a bigger goal. That can be as simple as keeping the company in family hands or as big picture as trying to make the world a better place.

Opportunity To Advance

Public companies tend to be very rigid in their hiring and promoting policies. If you start at the bottom, you’ll have to work your way up through many layers in a way that could take years. Family businesses are different. They are usually just looking for the best people for the job and are looking for team members who are loyal and talented. And as an outsider to the family, new employees often have fresh ideas about how to make the business better. I tell the students they may find that they have more chances to advance more quickly at family businesses.

Sustainability

Students tend want the startup experience — where they jump into the chaos and excitement of a new company knowing it could all go away at any minute — or they want stability. For students looking for a more grounded environment, I recommend family-run businesses that have been around for three or four generations. Any company that old will have gone through almost everything the economy can throw at a company. It’ll be well-prepared to weather the next storm while remaining nimble and able to flex for the changing marketplace.

Responsibility To Employees

The average tenure for a CEO at a public company is five years. At family-run businesses it’s 20 years. CEOs and employees may have similar tenures and are mutually invested in the company and their teams. Family businesses also usually consider their businesses, and everyone who works there, as an extension of their actual family. That creates a sense of caring and responsibility that you don’t find at many public corporations.

Ability To Contribute

Our students leave school eager to dig in and play a real role wherever they decide to work. Recently I heard of a student who did an engineering internship at a family business. He developed a new product idea and the company let him lead the development team in building it.

All of this advice comes with caveats. Not every family-run business (just like not every Evergreen business) is the same, and ultimately the most important thing is finding a good professional, developmental and financial fit. But I’m glad to see the students putting family businesses into the mix more and more often. They are real assets to these companies and will find real satisfaction in their careers with them.

Anne Smart is the Director of Family Business Center within the Quinlan School of Business.

What A Bankruptcy Taught Me About Perseverance

You’ll never get another job. It’ll show up on your resume. They’ll see it on your credit report. These were my fears as our company, Miller Broadcasting, headed into Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings in 1996.

I was 33 at the time, and scared to be going through something I believed had such a stigma. And I was scared the stigma was deserved, because somehow this was my fault.

But now it’s over 20 years later, our business is doing well and I see that bankruptcy as a lesson. By going through the fire, I learned how to Persevere.

My family’s been in the media business since the 1880s. We have worked in most major forms of media, including newspapers, radio stations, TV stations and online. These days our company, Rocking M Media, is headquartered in Manhattan, Kansas, and we own 31 radio stations. I co-own Rocking M with my mom, Doris, and my dad, Monte.

Media’s not only in my blood — it’s been my career. I graduated from Kansas State University in 1986 with a BS in radio and television and immediately began working for my family’s media businesses. I started in the collections department at TeleGraphics, our newspaper business, and as vice president of sales for Miller Broadcasting, our television company. That was my job in 1996, when we faced our biggest crisis yet.

The main source of revenue for our Kansas City TV station was the Home Shopping Network. But that year, after HSN was sold to Barry Diller’s Silver King Broadcasting, the company reduced its payments to us by half. Silver King was looking to cut expenses as much as it could, and that meant cutting our budget.

We had taken out hefty loans to build the station, and with the reduced payments, the only way to restructure those loans was bankruptcy.

It was my responsibility to formulate and negotiate many aspects of the bankruptcy, though as a family business we were all involved. I had to develop and prepare all our spreadsheets and documents for the bankruptcy plan we would submit to our creditors. But at first, I didn’t know where to begin. I didn’t know the difference between Chapter 7 and Chapter 11. And we couldn’t use our trusted corporate counsel, so we had to search for a good bankruptcy lawyer.

I suffered a spiritual crisis to go along with my financial crisis. The well-being of our employees and their families was resting on my shoulders. Explaining to them that Chapter 11 was our only option was incredibly difficult. It was hard not to feel like I had screwed up.

But I soon realized that Chapter 11 doesn’t mean the end of a company. First, some practical advice if you do find yourself in a bankruptcy: Hire the best bankruptcy attorney you can afford and try to get as much work done up front as you can.

The orderly nature of the bankruptcy process allowed me to work through some of my concerns. It gave us the chance to keep working, whether that meant filing a report or attending a court date, and moving forward one day at a time.

It also helped that I had the support of my parents, who were also my co-owners. We all kept reminding each other that family is more important than business, and that helped get us through.

The bankruptcy also deepened my faith. I come from a strong Catholic family and you can be sure we said an awful lot of rosaries during that time.

We came out of the bankruptcy a year later with our debt renegotiated, still holding onto ownership of the company and our TV station. And I am proud to say we repaid everyone in full, and no one had to take a write-down on their debt. We eventually sold KMCI to the E.W. Scripps Company in March 2000, for $18 million, turning a nice profit.

But that wasn’t the end of our difficulties. For years the media landscape has been rapidly changing. Over-the-air has given way to cable, which is now giving way to online programming. Each change made it harder to make money from media’s lifeblood: advertising. Even though my family started in the newspaper business, we sold our last paper in 1998. And when we sold KMCI, we officially exited the TV business. We realized the TV-station business model wasn’t made for mom-and-pop owners like us.

In 1998 we were again challenged by our tight relationship with HSN when they tried to block the sale of our Kansas City television station to the NBC affiliate. We ended up in a jury trial in United States federal court — something that would have panicked me earlier in my career. But thanks in part to the lessons I had learned during bankruptcy, I kept my cool and it paid off. The jury sided with us and we sold the channel.

I now feel these stressful situations taught me to be more centered, relaxed and thoughtful about business. I examine deals more thoroughly, and deal with crisis more calmly.

These moments that have taught me about Perseverance have also helped me become an Evergreen executive. In fact, I think being Evergreen is the definition of Perseverance. And to me that means never giving up on your company, even when you must go through something you don’t think you can do, like a bankruptcy or having to restructure. It means finding a way to somehow get through it, because you realize you owe it to your company, your team, your employees and your family. You’ve got to do it somehow. There’s no other option.

Christopher Miller is the president of Rocking M Media.

How An Evergreen Legacy Remains Strong After Losing Our Founder

In July 2012, my longtime friend, boss and professional mentor John Gongos phoned to tell me that, after a battery of inconclusive medical tests, he had been diagnosed with stage 4 cancer. But true to his optimistic, stalwart and “I’ll get through this” nature, John remained steady as he confronted a life that would be cut short at the young age of 51.

Just eight days later, I had to do something no COO ever wants to do — gather 100 employees to announce that our beloved leader had passed away from metastatic melanoma.

I had visited his home only a few days prior, and honestly didn’t see this coming. To say it was heartbreaking for me and everyone at Gongos doesn’t even begin to capture the gravity of the day. After all, John had founded Gongos Research in 1991; I was loyal to him and our company since the day we opened our doors.

The day I announced John’s death marked the moment I became a business owner, but it also marked a whole lot more. As Mark Twain said, “The two most important days in your life are the day you were born, and the day you find out why.”

That very day marked my “why” as I embarked on a path to create my own legacy.

Five years in, I can say that if there’s one trait of the Evergreen philosophy I have embraced above the others, it’s Perseverance.

In 1991, at 21 years old, I was one of three marketing researchers who joined John as he launched his own firm. Even though I was the intern, for some reason John was determined to bring me along.

Wide-eyed and driven, I didn’t have much to lose. After all, we already had a key client willing to join us. And working out of two cramped sublet offices was kind of invigorating. We were scrappy, and we did what we had to do. Although I was the youngest, I was in the thick of growing the business — writing proposals, preparing pitches to prospects, designing research studies and delivering the results to our Fortune 100 client.

And it paid off.

At the five-year mark, our firm had grown to 20 or so employees. By that time, we had leased our own office in a new building; not so long after, John made three of us minority shareholders in the business to reward us for our journey thus far.

Through hard work and by putting our people first, we grew. In 2006, we hired our first full-time marketing lead, organized our client-facing teams by industry sector and were about to become a top-50 U.S. market research firm.

But nothing good stays forever, and one of our minority shareholders suffered a massive stroke. While it devastated us all, it made us think more seriously about succession planning.

But this is not the tragedy that brought me to Evergreen.

In early 2012, John Gongos began to have stomach pains.

Prior to what was to become an unthinkable journey, John perhaps had a quiet succession plan of his own.

Nearly 18 months prior to his death, having learned a tough lesson about 50-50 partnerships in a previous business, John presented me with a shareholder edge, and had already appointed me COO. Yet, given his illness, he didn't have the time needed to fully prepare me for ownership. While we discussed succession planning, other priorities took hold. John wasn’t ready for this life turn, and honestly neither was I. A man only 10 years my senior had bestowed upon me far greater responsibility than my present COO duties.

But in 2012, our company’s fate was suddenly firmly planted on my shoulders, and my decisions were about to affect our possibilities and profitability. Sure, as COO I had internalized our growth and opportunities for our employees, but now I had to use my own intuition and experiences to drive decisions.

And there is a fundamental difference between operating as an executive and operating as an owner. As an owner, the weight of knowing that the financial well-being of our employees was now in my hands was humbling to say the least. After all, I had raised three children on our company watch, and the realization that my decisions would affect the spouses and children of each of our employees was an overwhelming feeling that I still carry with me today.

But persevere I did. And I didn’t go it alone.

My first task was to make sure our employees felt safe. Fortunately, they entrusted me to maintain an open-door (and, more importantly, open-heart) policy. Next I put into motion a communications plan to reassure our clients that they could continue to count on our company to support their missions. Slowly, I assembled my version of our company’s leadership team and put a plan into place to empower them and our future leaders.

Once I recovered from the shock of John’s death, I realized these new circumstances had reignited a sense of purpose in me. Three companies had approached me soon thereafter about acquiring us. I turned them all down, as John and I shared a commitment to keeping our company private while building a business that was about far more than profit.

Days before his death, I personally promised John that I would purchase his majority equity from his wife to ensure his family’s well-being. As a result, we held off on other expenditures, such as an office move to accommodate a growing workforce, and more closely aligned our spending with return on investment.

Finally, I needed to consider the future, and the legacy I was going to create. We redefined our evolution into a decision intelligence company. Market forces clearly required we move from collecting insights to helping our clients activate on consumer-centered strategies. After all, the world of big data was upon us and we had to seize it.

This meant hiring new talent — data scientists, visualization experts and designers. But more importantly, it meant gaining buy-in from employees. It was important for me to not rush this evolution and maintain our mantra of growing only as fast as we can find the right people.

Our long-held belief is that once we invest in people, we do all we can to retain them. I’ve made sure that as we evolve as a company, I’m listening and moving at a pace that balances comfort and growth opportunities for our people.

This deliberate pace has served us well. We are well into our evolution, growing to $23.2 million in revenues and 125-plus employees.

As a company that holds restless dissatisfaction as a virtue, there will always be work to do, and I ask our employees — both tenured and new — to Persevere through change, just as I have. I’m grateful for everything John taught me and for the chance to grow into the leader I am today. I know he would be gratified to see how we have progressed, and for the version of Gongos that is yet to come. And I trust that somewhere, somehow, he finds solace in the fact that he was right to fight for an intern.

Camille Nicita is the President & CEO of Gongos, Inc.

How Paced Growth Keeps Us True to Our Brews

Back in the early ’90s, when my company, Odell Brewing, was just a few years old, raspberry wheat beer was all the rage. Remember that? It was a big trend, and all the breweries started making that style.

We thought it was a beer designed for people who didn’t really like beer. We decided not to go down that road, a decision I’m still happy about. I don’t know for certain, but I’m pretty sure that today, not one brewery that hung its hat on making a raspberry wheat beer is still in business.

More recently there was the “hard” root beer trend. This was a huge volume play for the breweries that chose to jump on it, but it didn’t last. My personal opinion was that hard root beer didn’t really taste very good. And the breweries that did follow the trend ended up on a hard-soda hamster wheel, moving on to hard ginger ale and cream ale — always chasing what’s next.

We’ve passed up a lot of trends. Instead, we’ve always focused on creating a quality product that fits our identity, without chasing anyone’s literal flavor of the month.

I believe this approach has served us well so far. Headquartered in Fort Collins, Colorado, we’ve traveled by the North Star of Paced Growth since we began in 1989. In the process, we’ve become a true Evergreen company, though we didn’t even realize it for the first decade we were in business. Today we’re the 27th largest craft brewery in the nation and sold 120,000 barrels last year. We’ve grown a weighted average 11.1 percent annually since opening.

To us, Paced Growth means being able to grow with our own resources, without stretching ourselves to the point that we’re making decisions solely to generate more volume to keep growing. I believe this allows us to be more thoughtful about what opportunities we choose to pursue.

We have followed three principles that have allowed us to stay true to our goal of Paced Growth, which I’ll share.

One, as noted, is not following trends. I call that kind of growth “faddish” growth. Instead, we create our beers using committees inside our brewery, always with the same goal: to make a balanced beer with the right combination of flavors for the style, with no extreme or out-of-character flavors.

A second aspect of Paced Growth, for us, lies in carefully managing how and where we expand. Though Odell Brewing has grown enormously since opening, we’re only in 14 states today, choosing to develop markets that are deep, not broad. Even today, 64 percent of our volume is still in Colorado.

This means we don’t move into a new state haphazardly. We carefully interview our potential distributors to make sure we are putting our beers in the right places. We don’t want them to simply languish on a shelf somewhere. We also spend a lot of time physically on the ground in a potential new market to see if it’s a good fit. We often realize it’s not, and we give ourselves the freedom to walk away. This approach has definitely shaped how we’ve grown.

Our third Paced Growth principal is that we avoid outside money. We choose to finance our growth only with the cash we generate from operations or through traditional bank debt. Not bringing in outside money may constrain the rate at which we can grow, but we maintain complete control of our company, and to us, that’s more important.

This means we’ve turned down overtures for buyouts from the likes of Anheuser-Busch InBev and MillerCoors. We’ve also turned down overtures to sell to private equity firms. The truth is we were never tempted by these conversations at all. Yes, they would provide a payout, but we were much more interested in what the future arc of our business would look like.

We also wanted the people who worked with us to be in this business for a long time and not beholden to outside investors with different, short-term interests. Interests that might change the culture. It’s happened before.

For example, in 2015 Constellation Brands bought Ballast Point Brewing & Spirits. All three founders were subsequently gone within a year and a half. We didn’t want that.

Instead, Odell Brewing became employee-owned in 2015. Now 51 percent of the company is owned by executive team managers, the founders own 30 percent, and 19 percent went to an employee stock plan.

The truth is, it’s been easy for us to stay focused on Paced Growth because we like what we do and never started this for a big payday. It was what we wanted to do with our lives, and still is.

We want our company to last for 100 years and beyond, and we’ve come to understand it’s much easier to take care of the needs of everyone in the business — now and into the future — if we simply grow at a pace that’s sustainable.

Wynne Odell is the CEO and Co-Founder of Odell Brewing Company.

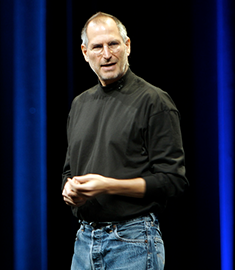

The Evergreen Message In Apple’s Famous Tag Line

This video captures legendary Apple CEO Steve Jobs at a crucial moment. He had just returned to the helm of the company that he had founded, and been fired from 12 years earlier. The company was offering dozens of computer models and had shifted to competing on the same terms as the rest of the computer industry — technical specifications of speeds and feeds. Apple’s brand and team had suffered. In this video, Steve explains to his marketing team that Apple’s brand must speak to Apple’s values and be much more like Nike. Every Evergreen leader should consider Steve’s challenge: Do your brand and marketing speak to what you stand for in the world — your Purpose?

(Photo: Ben Sanfield)

How To Harness What I Call Ketchum Flow

Six years ago, my family and I left our busy lives in Los Angeles and moved to Ketchum, Idaho, a town we initially thought of as a vacation spot. Our decision was not based on hours of agonizing discussions. Instead, it was based on feeling and instinct.

In no time at all, I dropped into the Ketchum lifestyle, learning to fly fish, white-water kayak and mountain bike, all in the springtime of my mid-50s. Trail running became an obsession. I found these new activities all had one thing in common: They all triggered and engaged me in the experience of flow. I have since come to apply the techniques of flow to all parts of my life, with dramatic results. I am happier, more productive and more focused.

I’ll return to my story in a moment, but first let’s define what flow is and why it’s important, especially to an Evergreen business. Many of us have experienced flow, particularly during some kind of athletic endeavor. It’s often referred to as being in the zone. It’s those times of uninterrupted concentration, focused on a specific goal when you are responding to instantaneous feedback. Time collapses. You perform optimally. You are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter. As explained by Steve Kotler, co-founder of the Flow Genome Project and author of The Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human Performance, flow has four key attributes: selflessness, timelessness, effortlessness and richness. The synthesis of these is what drives creativity, enhances performance and generates deep sensations of satisfaction and joy.

This might sound a bit fuzzy, but there’s a real science to flow and deep data that quantifies its impact. The reason flow amplifies performance, learning and creativity is that when a person is in flow the brain produces a cascade of neurochemicals: norepinephrine, dopamine, anandamide, serotonin and endorphins. All of these are performance-enhancing chemicals and feel-good drugs. A 2013 study by McKinsey & Co. found that when executives operated at peak levels — in flow — their productivity increased fivefold. Unfortunately, these same execs reported they and their employees were in flow just 10 percent of the time. Imagine the potential outcomes of boosting that number.

So, how can we learn to tap into a flow state more regularly? Experts in this space believe one trigger is to do something of a high consequence, to take a risk. Risk drives focus in very specific ways. Fortunately, it doesn’t have to be physical risk. It can include leaning into business-related ideas that have some element of social, creative or environmental uncertainty. Taking risks, moving out of a comfort zone triggers the neurochemicals associated with flow, which are proven to help you focus and take in more information and process it quickly. Flow jacks up pattern recognition and makes it easier to link ideas together. It is this lateral thinking where the “a-ha!” moments of creativity can evolve.

I first learned about flow 20 years ago through the work of Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. At the time, I was working at the top of the media food chain, as a president for HBO and before that, Warner Bros. TV. Deeply intrigued as I was by the concept of flow, I didn’t apply the tools and techniques in any consistent manner.

Moving to Ketchum changed all that. I was surrounded by flow masters: extreme athletes and professional adventure junkies. I began testing my body in new ways. In the process, I learned the practical value of flow, because when you are bombing down a steep single-track trail on a mountain bike, wavering focus has immediate consequences that are quite unpleasant.

Ultimately, chasing flow states, in all aspects of my life, became a habit. Wanting to embrace the state as often as possible, I took a giant leap, left the corporate world for that of an entrepreneur and started what is today Flow Media Partners, a media advisory and transactional company I run out of Ketchum.

Surrendering to the unknown felt surprisingly exciting and satisfying, perhaps because I was unattached to any particular outcome. All that mattered was the possibility of the moment. That’s when things began flowing. In no time at all new connections, new projects and new experiences came flying into my world. I even coined a phrase for my state of mind at that time: Ketchum Flow.

I became more comfortable pursuing riskier ideas. For example, the day Oprah Winfrey announced she would be ending her talk show, my former partner at Warner Bros. TV, Dick Robertson, called with an idea to put Rosie O’Donnell back on TV in Oprah’s time slots. We had syndicated “The Rosie O’Donnell Show” back in 1996, and for six years it had been the second most successful talk show behind Oprah’s. The decision to do this happened in an instant even though it put us over the tip of our skis with no safety net.

Since Rosie’s original show had gone off the air, many industry insiders viewed her as damaged goods and high-risk. To us, we knew what she was capable of and believed she could, with the right show, succeed in the slipstream left by Oprah’s wake. We decided to do all of this without a studio behind us, something our counterparts in the industry thought was crazy. But we ultimately made a deal for the show with the NBC Owned and Operated Stations and the Oprah Winfrey Network. Unfortunately, “The Rosie Show” did not perform as hoped, but the deal was immensely lucrative for all the partners.

In many ways, Evergreen companies are more naturally designed to embrace and foster flow, if for no other reason than that they play for the long game and are not bound by the Pavlovian demands of quarterly earnings reports or the arbitrary exit strategies of private equity firms.

To create a flow-encouraging environment, give employees the freedom to step over the edge. They have to know the business allows them to take chances, but they need to feel safe doing so. There are different ways to foster this culture. For example, company leaders can host seminars or training sessions on flow.

This quote from Steve Kotler feels meaningful for Evergreen executives: “If your company is not incentivizing risk, you are denying access to flow.”

Scott Carlin is the Founder of Flow Media Partners.

What Can Evergreen Companies Learn From Family Businesses About Long-Term Survival?

Being a multi-gen family business is no easy task. The death rate (either through merger, sale or other means) is so high that this may mean that there are no general rules for survival, only exceptions. The principle of Survivorship Bias applies — maybe multi-gen survival in the family business context is a random phenomenon, in which case, this article may not be of much use.

What makes the study of family business interesting is just how highly differentiated the best practices are among successful multi-gen businesses. What works for one family may be anathema to another. Yet, the collective best practices form a mosaic from which we can discern some key strategies and themes. Those are what I wish to share with you today.

Before we start on this journey, you should ask yourself if being perpetual, or multi-gen, is really an appropriate goal at all. What will perpetual existence accomplish? Is this just about you or is there a larger Purpose? Businesses come and go. Fast-growing businesses and large businesses generally have increased risks of failure. Is what you are seeking realistic, sensible, shared?

As this question relates to family businesses, realize that many multi-gen family businesses in existence today were not predestined to become multi-gen. Much depends on timing, luck of the draw and the fit of offsprings with an opportunity, in terms of both age and stage. Necessity also plays a major role, as in a founder becomes ill and the next in line just takes over — that is how families work. I am sure many multi-gen success stories would embrace the statement of “had we known how hard this is, we would never have tried doing it.” Words worth remembering.

Here are the top 10 lessons (inverse order) that family businesses have to offer:

10. Good hygiene (and we don’t mean in the personal sense). This means that all of the equity ownership is controlled by a single person or entity that has a very long life. And make sure that there are no forced sales of equity to liquidate estate tax liabilities or other third-party liabilities, such as a divorce. For family businesses, this is a sine qua non. Fight procrastination.

9. Embrace professional management at all levels. This is particularly hard for family businesses. You must have first-rate human resources processes, and cultural fit is a big issue. You also need rigorous compensation and employee performance evaluation rules. For family businesses, the rules governing family hires need to be spelled out and followed.

8. A liquidity mechanism must exist for nonbelievers. No family can keep all of its members happy all of the time. A way to buy out family members on an acceptable basis (note: I did not say fair basis) is almost always necessary. Likewise, family situations change and a structure that prevents the exercise of free will is doomed to fail. Having an escape mechanism that is available, though never used, may be the key to maintaining solidarity.

7. Strong governance is essential. This is a process, not just an occasion. There must be a board, and it must function. Having independent directors with relevant industry and leadership expertise is very important, although some family businesses survive without this. Good governance that assures the alignment of the interests of stakeholders and managers is essential.

6. You must plan for the predictable life cycles of business and ownership. There will always be ownership and management succession issues — you must plan for them well in advance and have processes in place to address them.

5. Embrace Deans’ Twelve Questions. Is it a good idea not to sell or go public? Know what you are foregoing and why. Do this on an annual basis. Make the stakeholders commit in writing to the plan.

4. In the context of a family business, you must procreate but not too much! You also need the right kind of procreation — preferably passing on the “good” DNA of the founder of the business and little else. For an Evergreen company that is not a family business, this means you must have a way to perpetuate ownership for the future — either sale to management or other employees or donating stock to a nonprofit entity or some combination of these. Someone who shares your vision must always own and control your business — not easy, but examples exist.

3. For family businesses, family harmony is extremely important. For companies aspiring to be Evergreen, you need harmony among all stakeholders — have you identified them? Don’t forget spouses and the families of key constituents … unhappiness is highly contagious.

2. Have a purpose or reason for existence other than longevity itself. Family businesses that survive and thrive have a purpose that motivates all participants to work together for a common goal. More money is not a purpose. Have a mission that motivates the behavior you want. For families, legacy is often a driving force. Stewardship is a key concept.

1. Have a good business. Avoid cyclical industries, avoid leverage. A slow-growing business in a defensible niche may be just the ticket. Profitability needs to be sufficient to enable stakeholders to achieve financial independence outside of the business.

Spencer Burke is the Executive Vice President at The St. Louis Trust Company.

My Father’s Unexpected Gift

Abt Electronics was founded in 1936 by my grandparents. In the midst of the depression, David and Jewel Abt pooled their total savings of $800 to open a small storefront in Chicago’s Logan Square neighborhood.

My father, who passed away last year, started working full time at the family electronics store in 1953 and eventually took over the business. He and my grandparents were both Evergreen before there was a term for it. While the world has changed around us, we’ve stuck to their core values: Treat your employees and your customers like family, and you can grow on your own without needing to look for outside investors. Today, our employee family totals over 1,450.

That doesn’t mean there haven’t been hard times. The consumer electronics landscape has changed dramatically over the past 15 years. Thanks to Amazon and the internet in general, you can order anything you want, from toilet paper to a 60-inch flat-screen television, without leaving your house.

Consumers who venture out are likely to visit a big-box store like Sears or Best Buy if they want electronics.

My father and I had to adjust to these very real competitors over the years, but we did it in a way that always kept our customers and our employees at the center of our universe.

If you’ve been to a big-box store lately, you may have noticed the customer service was, shall we say, lacking. That’s because these stores have become so focused on the returns they are giving their investors that they’ve forgotten about the people who are their front line in any transaction.

We’ve countered that by empowering our salespeople. If someone walks in and shows a lower price, our employees can make the right decision without involving a manager. We give them the space to really help customers because their bonuses aren’t solely based on sales. Showing up on time and going above and beyond to offer our customers great service is reason for a bonus.

For example, on the Saturday before the Super Bowl, we had three separate people come in and buy flat-screen televisions for the game. Instead of the usual next-day delivery, our salespeople delighted the customers by offering same-day delivery to make sure the televisions were set up and working in time for the big game. This was easy to arrange because our salespeople didn’t have to ask a manager or owner before they made the offer. They know if it’s good for the customer, we’ll always back it up.

My father also insisted that we pay our employees more than our competitors pay their people. This helps make them feel that they are part of the Abt family. We’re able to do this because we keep every aspect of our business in-house. People will tell you that outsourcing is cheaper but not when it comes at the expense of quality.

We have our own drivers, servicemen, repairmen, gas station, woodshop and solar panels, and we even have our own backup generator. So, if something goes wrong — and in real life things can go wrong — we have someone right there to fix it or make it right. Our builders can make a custom stand for a television or a panel to help a refrigerator look nice if the space around it is too big.

Not only does this save money and time because we don’t have to track down contractors when something goes wrong, but it also maintains our reputation for excellent service and keeps customers coming back.

The proof is in the numbers and in the multiple awards we have won over the years — the Better Business Bureau’s Award for Market Place Ethics in 2017, Chicago’s Top Workplaces in 2016 and Top Places to Shop in the 2016 Consumer Reports magazine, to name a few. In 2016, our revenues grew 7% while revenues at other electronics companies declined.

Watching my father spend his lifetime putting our family’s core values into practice makes it easier for us to lead our business today. We watched, we learned, and we grew. But, his last action will ensure that we never lose track of who he was and what he taught us.

Soon after my father passed, my brothers and I learned that he had taken out a second life insurance policy we knew nothing about. But this policy wasn’t for us or our families or to handle any tax requirements. Instead, he had taken out the $10 million policy on behalf of our employees who had been with us two years or more. Almost everyone received a check worth $4,000 or $8,000 as a final gift from my father. The outpouring of gratitude and words of kindness for my father and our family left me in tears.

As we continue to grow this third-generation company, the memory of my remarkable father motivates us every day to be better and do better. To the very end, he put People First and trusted good things would happen. We will carry that core value and his wisdom with us forever.

Mike Abt is the Co-President of Abt Electronics.