Taking Employee Training to the Next Level

Not just at my very first job, but at the first few, I had an experience that I figured was normal; I was hired, I arrived to start work, I was shown a few brief basics, and I was left to figure the rest out on my own. Like many other first-time employees, I was lucky if I even got any training. In the best-case scenario, someone took me under their wing and taught me a few things, but for the most part, I was left to my own devices to understand what expectations were, how things worked, and what pitfalls to avoid. When I left the job, any learnings that I took away were the things that I had stopped to consciously consider and understand, all on my own, and which may or may not have been beneficial to my next work experience.

The young employees at Amy’s Ice Creams have an entirely different experience.

Because of the nature of our business, making and selling ice cream, we employ a great many young, part-time employees, many still in high school. We get some folks who stay with us for a long time, but mostly there is high turnover in those employees for obvious and very good reasons – they are preparing to launch their professional lives and scooping ice cream is just the first step on the way to an eventual career.

Our visionary founder, Amy Simmons, decided long before I got here that she wanted these young people to go away with learnings that would benefit them throughout their lives, so she built a culture and a program that ensure this happens.

The foundational piece of this is the requirement that every new employee participate in two classes: Open Book Management(OBM) and Company Culture. To be eligible for raises or promotions, these classes are a must. Before covid, we taught these in person, and each was a few hours long. We have since moved to zoom, but the requirement and the content remain unchanged.

At Amy’s, we practice OBM. Right off the bat this marks a huge difference from any of the places I worked early in my life. For the most part, I had no clue about what was going on in the businesses I worked in. Like many young people in their first jobs, I think I imagined that the company was making lots of money and it was all going straight into the pockets of the rich owners. Period. I had no sense of the nuance and complexity of running a business, from the necessity of accounting for each dollar to the importance of deep, careful planning and execution. About ten years after Amy founded the company, she adopted OBM because she thought it would make us a better company, and because she wanted ALL employees, even the young, part-time ones, to truly get to learn how a company operates from a financial perspective.

In addition to this class, we invite all employees, even those who have been with us for only a week, to attend our quarterly huddle. At the huddle we look at every metric associated with the previous quarter. We review the big questions through the details: what were our targets in our key KPIs? Did we achieve these targets? How did we perform in this area, how about in that one? Where are our opportunities? We explain Capital Expenditures, including refurbishing our stores, buying vehicles for deliveries and catering, new equipment, etc. We decide what to prioritize, and we go through all of that in our huddle. We hope employees will understand key decisions like why we maintain surplus funds and how we allocate profits at the end of it all. Once it’s all said and done, they should walk away with a decent understanding of the fundamentals of business, which they will carry with them wherever they go next. Most of all, we hope they will take away the importance of being very diligent with money, whether in their personal life or in the business.

The second class we require of all new employees is Company Culture. In this class we teach employees about our values, what we believe in, how we treat each other, how we respect each other, and how much we value serving our communities. We hope that the message is clear: to us, this is just as critical to running a successful business as the financials are. At Amy’s, everyone is welcome, no matter who you are. We have no biases or judgements.

Let me give you a personal example that I think illustrates what kind of a culture we are working to create and maintain here at Amy’s. Every year we participate in the Austin City Limits Festival. It’s a huge undertaking for us as a company. For three days, two weekends in a row, we shuttle four crews a day to and from the festival. One year, soon after covid, we were a bit short on staff and our Director of Operations asked if I would drive the van. I did, and it was so much fun that I now do it every year! I love spending that time with the young kids who work for us, talking about their experience, and what’s going on in their lives. Sometimes, at the end of the ride, one of them asks me what I do at Amy’s. They have no idea who I am, and frankly, I think it’s better that way. I don’t need them to know I am the CEO; it might make them uncomfortable and less open and this way it’s just so much fun. This is the culture that Amy has created–we are all important and no one is better than anyone else. I get to benefit from this amazing culture now, and I Iove it.

I have been here for five years and feel incredibly lucky to be part of such a wonderful, People First organization. Amy and I have experienced it as a great privilege to build and steward this exceptional company in partnership with our leadership team. As a team, through discipline, focus, and a shared vision, we have achieved more impressive results than if our leadership was concentrated in just one or a few top executives. This reflects our culture of sharing, and for us, the cultural piece is everything. We are proud to be able to educate our young employees about the fundamentals of business and the importance of counting each M&M and hope they will carry the lessons on finance and on culture forward into their lives. And we are grateful for our cohesive and dynamic leadership team, which has driven the growth, strengthening, and solidifying of the foundation that will serve us into the future, 100 years or more.

Tugboat Institute Gathering of Teams 2023

Last week, we hosted the fourth annual Tugboat Institute® Gathering of Teams. This extraordinary experience was significant in a number of ways. For the first time, we celebrated Gathering of Teams in its fabulous new location, Nashville, Tennessee. It was the first time we were able to host the event 100% in-person since the very first year, in February 2020. Turnout was fantastic; we were thrilled to welcome hundreds of Evergreen® leaders and their teams, from Evergreen companies across a broad range of industries, sizes, geographies, and generations.

Our three days together offered both structured and unstructured opportunities for attendees to connect, learn, explore, and celebrate. Energy was high throughout, as key team members got to engage and share with other leaders from Evergreen companies.

The formal centerpiece of the experience was our six TED-style talks. Two Tugboat Institute members were joined on stage by three distinguished friends of Tugboat and our own resident researcher to share their Evergreen insights into business and life.

Don MacAskill, Co-Founder, CEO, and Chief Geek at Awes.me, which owns the brands SmugMug and Flickr, kicked off the talks by sharing his insights on Pragmatic Innovation. As they built their company in the highly competitive technology industry, they learned powerful lessons about innovating wisely, and not falling into the trap of constantly chasing the wrong, flash-in-the-pan trends.

Ann Rhoades is credited with shifting the way people think about Human Resources. Through her work as Vice President of People at Southwest Airlines, Co-Founder at JetBlue, and now PRES of People Ink, she is largely responsible for establishing the people-centric mindset that a growing number of companies are now adopting. Her profoundly People First perspective has changed the way many business leaders think about how they treat, honor, and support their employees.

Jim Weddle served as Managing Partner at Edward Jones for 13 years, after a long career in the company. One of the most influential clients that he served in his time as a personal Financial Advisor at Edward Jones was Peter Drucker, creator of The Drucker Principles and author of The Effective Executive. In his talk, Jim shared some of Drucker’s important lessons on effective leadership, through the lens of his experiences as a leader at Edward Jones, and he added some of his own hard-earned wisdom as well.

Dr. Gary Kunkle is VP of Consulting Service and Research at Tugboat Institute and has built his current practice on mountains of private company data collected over many years, first as the leader of a company in Rotterdam that advised companies on geographic expansion strategies, and then as a researcher on projects for the states of Pennsylvania and Maryland as he earned his doctorate. In his talk, he addressed some of the most pervasive myths around growth.

McCarthy Holdings, Inc. is led by Chairman & CEO, and Tugboat Institute member Ray Sedey, who delivered a talk about the work he has done at McCarthy to bring about an important culture transformation. When he stepped into leadership, Ray realized that while McCarthy had always been an excellent performer, the culture of the company needed an overhaul. He shared the process they went through to become a healthier, more People First company, and importantly, he connects the shift to concrete and vastly improved results.

Our final speaker was the New York Times bestselling author Daniel Pink. Daniel’s important work includes the widely acclaimed When, To Sell is Human, A Whole New Mind, Drive, and most recently, The Power of Regret. With our ability to accurately predict and forecast even for the near future severely hampered by the increased pace of change in today’s world, Daniel focused on some strategies that will help us shift our perspective and better prepare for the future by doing our best to focus on improving our position, both personally and professionally, today.

Outside of the talks, most of which will be made available through our Evergreen Journal® in the coming months, attendees participated in a variety of smaller group discussions and spent time celebrating together as well. Whether the focus was professional or personal, the centerpiece was intimate and authentic connection.

Beyond the numbers, the less measurable ways in which Gathering of Teams 2023 marked its significance were perhaps the most wonderful and the most important. Being an Evergreen leader in today’s world can be lonely and challenging and can make you feel like you are swimming upstream. But when we come together, everything changes. To a person, we collectively gained strength from the knowledge that every member of our tribe, which is growing in numbers and in momentum, confirms our shared commitment to building companies that will last and that will contribute, in many different ways, to making our communities and the world a better place. If, in the beginning, it seemed like our vision was shared by a select few, it is becoming increasingly evident that our tribe is, in fact, significant and powerful, with Evergreen companies in every industry and geography. The Evergreen movement is gathering strength, and as we grow, so does our hope and belief that together, our impact that will make a dent in the universe.

The First $25M are the Hardest

I went to work for my father’s company, Wisenbaker Carpet, in 1991, 21 years after he and his brother had founded it. I had my fresh new college degree in Industrial Distribution, and I was ready to make an impact. In my first stint with Wisenbaker, after learning the business, I piloted new programs and initiatives, and we grew, over seven years, from a $25M company to a $75M company. I felt pretty good about my accomplishments. But it wasn’t until I embarked on my next venture, outside of Wisenbaker, that I learned a humbling lesson: the first $25M are, in fact, the hardest.

My father and his brother founded Wisenbaker Carpet in 1970. As a kid, during the years when they were growing slowly, I worked in the company in the summers doing a lot of different jobs, from working in the warehouse, to driving a forklift, to installing carpet and learning the trade. By the time I came back to work full-time for my father after college, I had a sense of the business, along with newly minted business skills and a pretty good understanding of industrial distribution and installation. I was ready.

As soon as I got there, I started to notice aspects of the business that seemed antiquated and outdated. For example, we had a paper system for taking orders and filing them in the various places they needed to live. It seemed old and inefficient; I had been learning about the power and efficiency of computers, so I decided we needed to computerize our process. After doing some research, I launched and led an initiative to create a new Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system, putting together a team and even writing some of it myself on Disk Operating System (DOS). The process of duplicating what had been a pretty good paper system in DOS took about three years, and when it was done, we were streamlined and able to manage a higher capacity than our paper system had allowed.

Another project I undertook was a reorganization of the sales function from a staffing standpoint. Through my experience working in sales, I had realized that we were asking people to do more than one job, and that it was not possible for them to be fully successful as a result. Our salespeople were also doing the work of account managers, and they not only didn’t have the time for that, but they also lacked the skills. The reorganization allowed us to scale the company and leverage our people. The leap from $25M to $75M in seven years represented the fastest period of growth the company had seen by far. By the end of this period, I had been promoted to President, and my father was CEO.

During this time, in addition to carpet, wood, and vinyl floors, we added tile, countertops, and showers to our product and service line. We changed our name to reflect this expansion and became Wisenbaker Builder Services. Corian for countertops was all the rage at the time; in short order, we became the largest fabricator of DuPont Corian in the United States. But a few years in, demand started to shift toward stone countertops. I was interested, so I did some research and settled on quartz as the right product for us. We started to bring it into our product line, which did not make our suppliers at DuPont happy. They threatened to cut us off. At Wisenbaker, it was clear that we had to provide the products that our customers were asking for, so we decided to risk losing the relationship and chose fidelity to our customer over fidelity to our distributor. We were going to diversify if that is what our customers demanded.

Throughout the negotiations with the DuPont distributor over this disagreement, I had been the point person on our side, and the person on their side was a young man about my age – early 30s. As we sought a solution to the conflict, he had an idea: What if Wisenbaker stuck to DuPont Corian, and he and I left our respective companies and together, started a new one, selling the quartz countertops I wanted to bring in? His company agreed, my father agreed, and we took the leap.

My partner and I started a company called US Stone. We didn’t bootstrap it; we were able to leverage the two parent companies, which enabled us to negotiate with Bank of America, take out a sizeable loan, and get to work. We got an office trailer and started building a factory.

As we built our business, the challenges and the demands on our time were extreme. We struggled to find a supplier that would work with us and still allow us to own our own brand. We settled on one in Italy, which meant frequent trips overseas. Meanwhile, I had four kids under seven at home. We had plans to create the industrialized fabrication process that didn’t exist, but the hurdles were endless, and included things that I would never have imagined.

Here’s a simple story that illustrates how it went in the early days. One day, my partner and I were sitting in the office trailer we had rented. The sun was coming in the windows and making it hard to see our computer screens. We decided we needed blinds for the windows. There was no one to send on this errand, so we eventually found time to go to Home Depot and buy them, and then they sat of the floor for months because we were too busy to put them up. We also ran out of toilet paper – there was no one to go buy it but us. Little things like this made me realize how much we take for granted in established companies. Starting a new business, you have to be responsible for every little detail, including the tiny and very un-glamourous ones. It was exhausting.

Keep in mind that we were not bootstrapping this business like my father and uncle did. We had money and we had a plan. But we had no systems, no processes, and in the early days, no people. We were starting from scratch, and we had to do everything. Suddenly that paper system I had replaced at Wisenbaker looked pretty good.

US Stone made it; we were able to build and scale it quickly, in great part thanks to the financial backing our parent companies had facilitated. It was a real lesson in building something from the ground up. After seven years, I was ready to leave this now-successful venture behind and return to my Evergreen® roots at Wisenbaker.

When I came into Wisenbaker as a punk kid out of college, thinking I would be the one to turn this small little company into something big, I failed to give my father credit for the work he had done to get the company where it was. I learned through my experience at US Stone that the journey from $0-$25M is incredibly hard. In many ways, it’s much harder than the journey from $25M-$75M, because the foundation in this second phase was solidly in place and the resources to do the work existed. I gained a whole new appreciation and respect for the incredible work they did.

Why I Work With Lobbyists and Why You Might Consider it Too

In 2019, a fellow Tugboat Institute® member shared a short talk on working with lobbyists. Up until that point, I had engaged with lobbyists twice, to work on issues specific to a school district and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), respectively. Each time, I was already deep into my work solving the two problems involved, and the lobbyist work was something we tacked on partway through because it became apparent that we had to. But when I saw this talk in 2019, I got to thinking–maybe this could or should be a more regular part of our process?

There are many different reasons to engage a lobbyist, and there are many different types of lobbyists. Some specialize in working with county governments or school districts, some work exclusively with agencies or alliances, some are partisan and some are not, some work at the state level, and some at the federal level. The landscape is complex and can be intimidating, but it comes down to this; there is virtually no industry that is not significantly influenced by regulation. Would you prefer to be at the whim of the regulating agencies, or would you like to have a chance to ensure that they understand the issue from your point of view?

Gaggle operates in the education industry, providing solutions to help K-12 districts manage student safety and well-being on school-provided technology. Our whole industry is driven by government funding. The state departments fund their districts, the federal government funds the Department of Education, and both distribute a great deal of money through annual budgeting and grants to fund our public education system. Sometimes the goal in engaging lobbyists is simply to ensure that your legislators fully understand the issues on the table, and structure grants and programs in such a way that your product is eligible.

Like many smaller Evergreen® companies, we often face competitors who are huge and well-funded, but who do not deliver the product they promise, in great part specifically because they are not Evergreen, and prioritize profit at all costs. If we don’t engage lobbyists and enter the conversation, the legislators and politicians crafting the regulations will only understand the issue from the point of view of our loud and wealthy competitors, who have a significant presence in the state and federal houses. They need to be educated, and most of the voices who seek to educate them have their own self-interest at heart.

Once you start to think that entering the lobbyist ‘game’ may be important, your next question might be, how? I admit that it can get complicated pretty quickly. In short, there are lots of different types of lobbyists, but no matter who they are, once you engage them, it is their job to become an expert on the issue you are dealing with. Some are independent, but most work with firms. And it’s a game of conversations. If the issue on the table has to do with state regulations, they will travel to the statehouse and meet with the staffs of legislators and committee members, and sometimes, with the elected officials themselves. If it’s a federal issue, the layers of people between you and the legislators multiply, and you will find that most of the lobbying happens with the staffs of the people who will be signing the legislation. It’s a little shocking, by the way, to what degree our country’s regulatory structure is shaped by these staffers, who are typically just a few years out of college!

The bottom line is this; it’s best to stay out in front of the regulatory shifts that are in the works if possible. Our first experience working with a federal lobbyist was a time when we were on the defensive and forced to react. As the pandemic took hold and online education took center stage, our industry was suddenly under much more scrutiny than ever before. We received an accusatory letter from the office of Senator Elizabeth Warren, requiring that we answer ten very specific questions about the ways we were (or weren’t) protecting minority and LGBTQ+ kids. We are in the business of protecting kids, so this was something of an affront, but it made us realize that the new privacy policies that were in the process of being shaped were operating on a number if ill-conceived assumptions, because the legislators only had a limited perspective on the issue. We hired a federal lobbyist to help them understand who we were and what we did.

Many in my industry are backed by Private Equity, and they just said, “Oh, let’s lay low and wait until this blows over.” But we were not willing to do that. We are part of a system–and in fact helped create that system–that is specifically trying to protect those kids, so we had to make them understand that. We are on a mission. We need people to understand and join us on this mission.

When it comes to regulation, there is a pendulum that swings one way and then it swings the other. Right now, we are swinging heavily toward more regulation, and I expect we will be here for about another half decade. Enormous, important decisions are being made about how government money is rewarded, what the criteria are for entrance into certain markets, what level of tariffs or taxation we will experience, and even, especially in my industry–education–what exactly privacy means and how tightly it is controlled.

I know the reputation of the lobbying world is largely negative. Maybe people see it as a war of self-interest, where the entities with the most money typically prevail. I suppose to a certain extent that is true, but here again, the advantage of being an Evergreen company is significant. Governments at all levels like to feel they are doing the right thing. Once they understand the value proposition of your Evergreen company, with its People First orientation and its commitment to adding value to the communities it serves, they can feel good advocating for your point of view. They hear from corporations all day long and they can see the difference between us and them. Further, as the leader of an Evergreen company, I can step into this ‘war of self-interest’ with a clear conscience, because I know that the interests I am trying to protect extend beyond my bottom line and even my employees. I am working for the good of every student and district we serve and everything we do is aimed at improving their experience in the world and protecting them from exploitation.

With this mission, if hiring lobbyists is the most effective way to share it and ensure that we have the space and funding to do our good work, then hire lobbyists we will. And I will sleep better at night knowing I am doing everything I can to help advance this mission and help students across all of the states and districts we serve.

Making Sense of Evergreen Leader Optimism Going into 2023

Dear Friend of Tugboat Institute®,

As we step into a new year, I carry with me interesting insights from our recent Tugboat Institute Member Pulse Survey from early December. These members span 20+ industries across the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Contrary to what others are saying in the media and elsewhere, most of our members surveyed do not think we are heading into a major recession, or even a hard landing. Overall, over 60% of our members are expecting 2023 to be a growth year and nearly 20% think it will be flat. 45% of our members view the current economic environment as good to very good and 51% view it as ok--not good but not bad. Few view the current economic environment as very bad.

The difference between their cautious optimism and what we are seeing and hearing on the national stage may, in fact, reflect the differences between Evergreen® companies and public, PE-owned and VC-backed companies that dominate the media and capital markets. Let me explain.

Inflation, supply chain uncertainty, and labor shortages are just a few of the issues that have presented challenges to most businesses in the past year or more. These pressures are certainly real, for Evergreen companies as for all others, and I do not mean to downplay any turbulence or headwinds they are currently causing you. However, I think that a look at the difference between the way Evergreen companies operate and, for example, the way private equity (PE)-owned and venture capital (VC)-backed companies operate might explain this relative optimism in the face of today’s challenges.

PE firms are highly competitive, with over a trillion dollars in dry-powder as an industry. To win the deal, they must pull every lever they can in their modeling, post-acquisition planning, and use of leverage to maximize their offer price while still earning a PE-level return for their investors. This leads to substantial amounts of debt relative to equity in their purchase prices, often 2:1 and even 3:1. In a low interest environment, more leverage is a great way to boost equity returns even higher. To further maximize every dollar of equity return, PE firms often stretch for the lowest possible interest rates, even during our recent period of historically low rates, which means variable interest loans.

After closing the deal, the typical PE playbook is to raise prices and cut costs as much as possible to generate cash to service the debt, typically through layoffs and elimination of any spending that does not feed immediately back into the bottom line. They will also move to squeeze suppliers on costs and payment terms, cut long-term investments, cut charitable giving, reduce product and packaging quality, sell off real estate, sell off divisions, reduce benefits, replace expensive, tenured managers with young go-getters, etc.

But what happens when the economy unexpectedly slows? Post the massive COVID-related stimulus, and with interest rates rapidly spiking up as the Fed belatedly fights high inflation, conditions can change very quickly, as we have seen in the second half of this year. For these companies, there is a further cash crunch as revenues soften, costs rise, and the earlier pursuit of super-low variable interest rates becomes a time-bomb, significantly raising the amount of cash flow directed to debt service as rates reset. It’s ugly.

I bet many PE-backed CEOs felt forced to take actions in 2022 that they despised, including moves against their employees, customers, suppliers, and communities. They undoubtedly viewed every move as necessary to preserve their jobs and the companies they lead so that ultimately, a small number of PE owners can continue to financially benefit, along with the pension funds that provide half their funds. How would it feel to be an employee in those PE-backed firms? Remember Doug Tatum’s analysis that over 20% of all jobs in America are working for firms with PE ownership, thus living under this tough playbook.

A VC-backed company faces a different set of challenges today, but they are daunting as well. Instead of the debt that funds so many PE buyouts, the VC playbook for over two decades has depended on willing and generous investors funding continued losses in the pursuit of get-big-fast (GBF) and market leadership. While the VC industry pre-Netscape IPO was remarkably capital efficient (recall that the three trillion-dollar winners of Amazon, Google, and Microsoft hardly needed any equity capital pre-IPO), that was no longer necessary as money flooded VC firms. With the exceptionally low interest rate environment and excessive liquidity from quantitative easing created by the US Federal Reserve after the Great Recession, the return on fixed income portfolios dropped to almost nothing, and institutional investors had to move to riskier assets, like VC and PE, to find higher returns than the stock market to achieve their return goals or obligations. VC promised, and for a time delivered, these increased returns, enjoying the tailwind of a public market with overinflated asset values in tech, software, and crypto due to those same near-zero interest rates, and therefore attracted even more money from all sorts of sources.

Today, with valuations of unprofitable tech companies getting destroyed and the FAANG stocks down by half since the end of 2021, VC and later-stage speculative investors (Tiger Global, Softbank, for example) have pulled back their investments, as public companies quickly become worth less than private ones. The mantra now in the VC circles is get to profits, since funding risk has gone exponential and an unprofitable firm cannot count on raising new rounds at anywhere near the current paper valuation, if at all. Layoffs abound in both private and public technology firms as they try to find a profit discipline. Through this process, they are also destroying their once fun, lavish, and friendly cultures. It is going to be really tough to change a culture from playful and undisciplined, with prolific spending and questionable employee effectiveness, productivity, and accountability, to a culture where every dollar matters, there is tremendous Esprit de Corps, and Pragmatic Innovation reigns. Most of the private GBF companies won’t make the shift successfully.

In contrast, Evergreen companies are not beholden to outside investors. They are typically debt-averse, and if they do carry debt, it is in a reasonable amount, and often backed by hard assets, not the goodwill of outside investors. Evergreen companies grow steadily over time and from their own profits. While this may mean slower growth at times, if you compound their growth rates over decades, it leads to large, meaningful, well-run businesses. Evergreen companies are grounded in a foundation of actual, real value, delivered to employees and customers, and profitability. This equates to far greater stability than their PE and VC backed competitors. Evergreens are better positioned than anyone to weather downturns and therefore, to survive and thrive into the recovery.

I certainly do not mean to suggest that Evergreen companies are not facing headwinds in today’s economy, nor do I intend to diminish the reality of the struggles you are facing in your company. Simply, as I listen to your feedback and hear the cautious optimism that stands out against the backdrop of a much more pessimistic message from the collective non-Evergreen community, I see strength in our difference.

Because of the decisions you made not to fall for the sirens’ song and pressure of raising outside money, overleveraging, selling out to PE, or going public, during the past decade (or even further back to the beginning of the 40-year march in declining interest rates), your foundation is strong today. You have an incredible competitive advantage, existing for a deeper purpose, growing slowly and steadily from your own fuel, investing in the future when others are on defense, taking care of your people, and protecting your values and independence.

For over a decade, it felt like money was plentiful and cheap; between low interest rates, excessive government liquidity, and an abundance of aggressive investors, it was. Therefore, companies who were willing to take massive investments and grow as fast as possible to get as big as possible as soon as possible appeared to be winning. Today, the winds have shifted, and I believe they are blowing in our favor. It may not be intuitive to most to be optimistic at this moment, but if we think about the difference between an Evergreen company and its competitors, it does make sense why you are.

Wishing you the very best in 2023 and deeply grateful to you, your teams, and your families for being the quiet, stable backbone of our economy.

Warmly,

Dave Whorton

CEO & Founder, Tugboat Institute

Write Your Personal Strategic Plan

For seven years, I was a member in a Bay Area based CEO group focused on leadership, growth, operations, and innovation. As a young leader, I was far younger than most of the other members, which was both exhilarating and humbling. It was an amazing group, but I learned something especially important from a man named John Carpenter; in many ways, he became my mentor. Over the years in the group together, he witnessed my transformation from aspiring leader seeking to grow my company, to a newly married man, to a new father. He invited me to lunch one day, proposing to work on my strategic planning for the following fiscal year. After showing my current version, goals, and aspirations, he fairly pointed out what needed significant improvement, and then asked me “to show my personal strategic plan.” I was stumped; my what?

As an experienced leader and very wise man, John had a perspective I was unable to see clearly at the time. He knew how dedicated I was to Diamond Construction, the company my father founded and grew, and for which he was now providing the framework for succession. He also understood how dedicated and available I wanted to be to my growing young family, something I had learned from my other mentor, my father. Further, he knew about some of my other passions, which included climbing mountains all over the world and trekking at high altitude. Lastly, he had watched countless ambitious young leaders throw themselves into their work, often at the expense of their families and personal lives. Many of the CEOs in our group were divorced and had in some way sacrificed their personal lives for their professional ones. He sent me home with an assignment; write a one-page personal strategic plan for the coming year.

Staring at a blank page and reflecting on how to frame my personal life strategically, I contemplated what that even meant. A week prior, I would have easily replied with generalized framing for my personal objectives as they related to relationships. But now, I was faced with a daunting reality; I must accurately write and acknowledge where I was currently, where I wanted to be, and how I was going to get there. This made me realize that, although my intentions were to be the best husband, father, friend, and community member, I was failing myself in multiple areas. So, as in a business plan, I created an outline of extremely meaningful parts of my life: relationships, mental and physical health, philanthropy, education, impact, spirit etc. That created the framework to infill specific goals I believed would help benchmark growth from the prior year and plan. The strategic goal here is personal growth– a rigorous, unapologetic commitment to those areas of life which define personal enlightenment.

What did any of this have to do with my business? Everything. As John pointed out and as I started to see clearly through the following year, my business and personal strategic plans were dovetailed, and as I learned to manage myself, I finally started leading. Many leaders have the best intentions across the board but will prioritize business over themselves and often over their families when the two come into conflict. As any business leader knows, this happens more than we’d like to admit. The act of writing it down, acknowledging it, and reviewing and managing it creates metrics of growth outside the standard societal proverbial yardsticks.

I took my first personal strategic plan back to John and showed him. “Great, now hold it up next to your strategic plan for Diamond Construction. If you cannot achieve something in your business strategic plan and also honor these priorities, take it out of your business plan or think strategically about how you will achieve it without compromising yourself.”

Does this mean I’ve sacrificed business growth and opportunities to put myself first? The exact opposite. Since starting this process, I’ve grown our enterprise from being a residential construction company into a vertically integrated development, investment, construction, and innovation company. I finally understand strategy. When my plans conflict, I ask myself, how can I make both happen? I reformulate the strategy, with this new perspective. I have grown my business every year for seven years in a row, so I can confidently say that the personal plan does not mean personal success over business success; it just means crafting plans thoughtfully. Sometimes that means hiring a new team to run a new project or altering a timeline, but I have found that it is always possible to adjust in a way that makes both plans possible. I am growing my business, but I am doing it more efficiently and with a great deal more self-awareness. Most importantly, it is now sustainable.

For my employees, this has turned out to be extremely important as well. They see me value my personal life, which forces me to help them value their own personal lives, and it makes me more aware of and sensitive to their personal needs. I can be there for them in a way I could never have been if I only valued myself as a professional–it humanizes the business. Frustrations of wanting more from someone have turned into empathy, marking a shift from disappointment to understanding.

With proper personal strategic planning, one can better align and manage their overall life goals. By forcing oneself to document and prioritize personal goals, like in business, self-awareness is heightened, and personal relationships benefit. I drop my children off to school every day; it was a commitment I made in my personal plan. My favorite part of the day is those 30 minutes talking to my 3- and 5-year-old about life, what they plan to do that day, what they plan to learn. I would never have made that a priority before, but now I realize they have given me the opportunity to start each day as the best version of myself and I wouldn’t change it for the world.

The Pre-Mortem

In his new book, The Power of Regret, Daniel Pink argues that regret is not a negative emotion we should seek to avoid, but rather a positive one. It is regret that allows us to examine our mistakes and learn from them, so we don’t repeat them over and over. But what if you could take it one step further and learn from your mistakes before you even make them? At Truss, we have been working to learn from potential mistakes before we make them through a process called pre-mortem.

Pioneered by Gary Klein in 2007, the pre-mortem was designed to reduce the frequency of failure and is based on a psychological principle called a counterfactual, which asks how you can imagine something that has not yet happened and, further, how you can draw use from that imagined future. In contrast to the post-mortem, which examines the outcome of an initiative once it is over, the pre-mortem also focuses on a specific initiative, but ideally before it begins or in its early stages. Here is what it looks like.

As you prepare to launch a project, you assemble your team. You tell them, “I want you to imagine six months into the future. The project has launched, we are well into it…and it’s been a complete failure. Our colleagues, customers, and partners are all angry or disappointed, and we are embarrassed”

Pause. Let that sink in.

Then you ask, “What happened?”

Usually when I first launch this question into a room, I am met with silence. We aren’t used to being asked to express vivid failure, and there’s often a bias for keeping our doubts silent. As a leader, I often start myself; I imagine a failure that is grounded in my own error or oversight. When the team sees that the potential problems could implicate even the CEO, they become more willing to play along. A good practice is to have everyone write their thoughts down first. This has the advantage of ensuring that your team members are sharing independent, diverse perspectives. Eventually, your team starts sharing: we took a risk on pricing and didn’t react quickly enough when we needed to adjust; we didn’t execute our media strategy properly; our competitor came out with a better product right after we launched. We encourage team members to share potential failures grounded in both internal and external factors, and we get it all on the table.

Sometimes the ideas get ridiculous, but even those are important – having a laugh can reduce the hidden anxieties of the team in a safe way. The goal is to get as wide a variety of possibilities as possible, and ideas that come from each person’s specific area of expertise. It can get quite lively once you get going, and you start to realize areas where you need to protect the project in a way you hadn’t previously imagined. Then, as a team, we look at all the ideas we have generated, organize the fixes for the mistakes we haven’t made yet but might make, and set about implementing them. Now your team has action items, they have learned from each other’s perspectives, and they have the time and the clarity to work to mitigate the bad outcomes you have imagined. The subtle but crucial key is for the team to invest in imagining a vivid outcome of failure. By doing this, they will usually uncover new obstacles that they can fix together. It is remarkably effective.

One concrete example of a time when we used this at Truss was back in 2017, when we were considering making salaries internally transparent. We were interested in improving equity and thought this would be an effective way to do that. Before we made the decision, we did a pre-mortem. We asked ourselves, what could go wrong here? Well, people could dislike it so much that they would leave the company. That would be a terrible outcome. How do we mitigate the risk of that happening? To solve for this, we decided to find out ahead of time how people felt about it. Simple, but we hadn’t planned it initially. We polled our employees, asking them if, hypothetically, they would be for or against this move. We learned that most were for it, and we learned what the specific concerns of those who weren’t sure were. We were able to fix those issues before we made the shift and, importantly, before they became big problems.

Another way you might use the pre-mortem is directly with your clients. It requires a great deal of trust so I might recommend that you have a few cycles of project execution, postmortems, and addressing issues first. This establishes the practice that postmortems are about learning, not blaming, and following through with actions tends to increase trust. As you build trust, you can introduce the pre-mortem before the next initiative. When we do this with clients, they initially can’t believe that we are willing to consider that we might make a mistake. But then they start sharing things that they are worried about that we might never otherwise have known. The practice of pre-mortems has been an incredibly useful practice for building client trust, mitigating risk, and planning successful projects.

I use this process in my personal life as well, such as when I chose between grad schools. When I have a big decision to make – especially when I am deciding between two great choices– I created the habit of writing myself a letter. In the letter, I imagine I have chosen either option A or B, and I am several months into my life post-decision. The crucial step is to write out in vivid detail what that future life in choice A looks like: where I’m located, who I interact with, how I feel, even the sights and sounds. One of two things usually happens. Either I know within a couple paragraphs that choice A is wrong, or I get excited by my description of the future. Then I put the letter in an envelope, put it on my mantle, and open it again six months later (yes, I’m old school, you can do it electronically and set a reminder). At that point, I am well into the reality of life post-decision and I can compare the two versions. It allows me a window back into my thinking when I made the decision, and the opportunity to re-evaluate my choice. Often, it turns out to have been the right choice, but sometimes it doesn’t. By reminding myself of my original intention, I can correct course, move forward, and re-evaluate how I made the decision, given the information available. This sometimes is the most powerful part of the practice of using counterfactuals to make better decisions.

This is a quick overview of a complex process that is highly Evergreen®, because it empowers all team members to contribute, in a risk-free environment, to problem solving and troubleshooting. It can influence how you make decisions, what level of trust you enjoy within your team and with your clients, and even how you think about future endeavors.

There is obviously no way to clearly see what really does lie ahead, but the learning that can come from this peek into the future is profound, meaningful, and actionable. We get the benefit of learning from mistakes that Daniel Pink advises us to embrace, but we get to do it ahead of time, when there is still time for our learning to influence the present. It’s the best of both worlds.

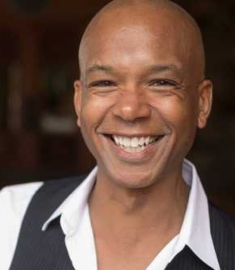

Everett Harper is CEO & Co-Founder of Truss and author of Move to the Edge, Declare it Center, where you read more on practices like the pre-mortem.

*photo credit: Asa Mathat

Lessons in Leadership I Learned from my Baseball Coach

One of the most effective tools I’ve learned in the many leadership trainings I’ve done over the years is the importance of journaling. Journaling creates the time and space to pause, step back, reflect, and gain insight. Out of the practice of journaling, I’ve come to many important realizations and gained many significant insights. One of them is this; I learned some of my most important lessons in leadership from my high school baseball coach.

I remember one time early in my career, we were in a close game and I got a chance to come in. The bases were loaded with two outs, and I got to pinch hit. I came in and I hit a double in a gap to the fence. I cleared the bases, and I stopped at second base, eyes fixed on my teammate who had started at first base. I held my breath, hoping he would slide into home plate and score. He did! We scored three runs, and I was excited. My coach called time out from where he was coaching at third base, and he called me over

Coach Gene Schultz was never an emotional person, so you never really knew what he was going to say. I got over there, expecting maybe a pat on the back, but he made no comment about the double, didn’t say “good job.” Instead, he asked me, "Where should you be right now?" That was it. I said, "You tell me." To which he replied, "You should be standing right next to me here at third base. You got caught up in the drama and watching the play, but you should be right here." I had failed to follow his most important golden rule: We over Me. My mental percentage dropped.

In the small town in Iowa where I grew up, baseball was it. Everybody played, including me. Our high school was small, but we just happened to have a great baseball team; we won numerous state titles over the years and made a real name for ourselves. We didn’t send a lot of players to play college ball, and we didn’t send any to the Major League that I am aware of, but before, during, and long after my time on the team, we were great. The reason was clear; for 45 years, our team was coached by Gene Schultz. To this day, Coach Schultz is the winningest high school baseball coach in the nation.

Coach Schultz played baseball in college and then came straight to our high school, where he stayed for his whole career. He was not like other high school baseball coaches at the time. Like all the others, he was a fanatic for stats. He kept stats on all the things you would expect: batting average, on base percentage, stealing percentage, balls, strikes, wins, losses, etc. But he spent most of his time tracking different stats, which he called Mental Statistics. They revealed what he considered to be the most important part of the game: where was your head during any given play? If it wasn’t in the right place, you were not contributing your best to your team.

Here are a few examples of things he kept stats on. If you're an outfielder, did you throw the ball to the right place? When you threw it back in, did you hit the cutoff person? Did you throw it to a base? If you're playing center field and the ball is hit to right field, did you go back up your partner, or did you just stay in your space? The list was long. He used them to calculate what he called mental percentages. Ultimately, there's only one right action in every scenario; what percentage of the time did you see it, and did you do it?

As I’ve reflected on the lessons I learned from Coach Schultz back in high school, I can see two main reasons for his great success: attention to detail, and the “we over me” mindset.

The mental stats are a great example of his extreme attention to detail. To help us improve our mental percentage, he relied on repetition. We basically had the same two-hour practice over and over for all the years I played for him. Our focus was always the same: practice plays and then consider; did you have a plan for what you were going to do if the ball was hit here or if it was hit there? Were you thinking ahead instead of reacting in the moment? Were you aware of where people were on base? Our consistent and intense focus on this, over and over, helped us get better and helped us win.

The “we over me” mindset perhaps explains why, despite his incredible number of wins, Coach Schultz did not produce a bunch of great, professional ball players. He wasn’t coaching players, he was coaching teams. On his team, there was no room for ego and no room for individualism.

In business, all of this translates to a mindset as well as specific behaviors. Attention to detail and “we over me” sit at the foundation of both. At World Class Industries, I measure for accountability, but mostly I measure for improvement. There is always learning going on, and the attention to detail helps me capture and apply that learning. As for “we over me,” this takes us right back to Stephen Covey. If you think back to The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, you will recall that one of them is creating win-win scenarios. If you are winning because someone else is losing, or if you’re looking good because somebody else is looking bad, that is not a sustainable approach to winning.

As a People First, Evergreen® company, in it for the long haul and aiming to last 100 years or more, the short wins and the individual wins just won’t cut it. Gene Schultz coached us to win, but we had to win the right way. As a team.

Why We Hired a People and Culture Leader, not a Director of Human Resources

Conventional business wisdom tells you that when your company grows to about 100 employees, it’s time to hire a full-time Human Resources Director. At Biohabitats, we are not quite there, but we began to feel the growing pains of not having someone dedicated full time to HR about two years ago. With eight bioregion offices scattered across the US and work throughout the world, the need to have someone solely dedicated to our team members’ well-being became paramount. As we began thinking about this position, we wanted to be sure it both reflected and reinforced our culture, and we couldn’t come to terms with the label ‘Human Resources Director.’

Traditionally, Human Resources is a management position. It is about making sure you are meeting the legal requirements you need to meet as a company, managing employee benefit programs, supporting your onboarding and offboarding processes, and resolving conflicts. Of course, we need to do all these things, but staying on the right side of legal requirements seemed like a low bar; we thought we could do better.

In our minds, humans aren’t resources, rather they are people striving for fulfilling, healthy, and secure lives within and outside work. For us, ‘People and Culture Leader’ seemed better; it both characterizes the roles and responsibilities of the position, while at the same time reinforcing our culture, identity, and purpose. You can say it’s semantics, and that it’s basically another name for the same position, but I would argue that language matters.

At Biohabitats, we restore ecosystems, conserve habitats, and support the regeneration of the natural systems that sustain life on Earth. We focus on managing projects and processes, not people. As a learning organization whose culture is underpinned by a belief in ecological democracy (the rights of Nature), we take our cues from Nature when it comes to organizational structure and relationships. For us, it’s about enabling our team members to fully express themselves, bringing energy, passion, and creativity to their work.

Our structure is based on three overarching principles: self-management, wholeness, and evolutionary purpose. With self-management, for example, our team members have high autonomy. They are accountable to themselves, their fellow team members, their clients, and to the Earth and all non-human beings. As we conceived of this new position, we wanted to focus foremost on cultivating our culture, nurturing team member aspirations, and fostering wholeness. We needed to be clear about what we value and what we want to achieve as an organization.

Our People and Culture Leader has been in place for a year now. People often ask if we notice a shift since Katherine started. The answer is a resounding yes. At a base level, we have doubled-down to make sure that Biohabitats operates from a Purpose driven, People First perspective by weaving our values, mission, purpose and the needs of our team into our daily practices. As an example, with one dedicated person, we are now better positioned to translate what it means to be a B-Corps and 1% for the Planet member into our daily operations.

Another great example is the creation of our Headwaters document. We recently revamped our policy manual and created, instead, a document focused around the tenets of self-management, wholeness and evolutionary purpose, and grounded in our values. In nature, the headwaters of a watershed is where many ecological processes begin their journey toward estuaries and the ocean. In a nod to this, we named our document Headwaters: A Guide to Biohabitats Benefits, Policies and Cultural Practices. The focus is not rules and regulations, but rather culture and people. In this guide we not only articulate our five Core Values, which include Revere Wild Nature, Heal Compassionately, Practice Wholeness, Act with Uncompromising Integrity, and Evolve to be the Best, but we have carefully organized all our benefits and policies to support these values. Ultimately, Headwaters serves more as an expression of the heights to which we aspire to rise, rather than the minimum depth under which we will not sink.

Further, we’ve been able to take many of the general things we do as part of running a business and lift them to a level that honors our focus on culture. For example, as part of our open book policy, we routinely hold quarterly meetings with the entire team to review our financial performance from the preceding quarter. Now that our People and Culture Leader is leading the effort, it has become so much more than simply a financial performance review. We now weave in our social and environmental impact performance, our DEI work, and other initiatives that directly speak to Biohabitats’ culture and values. In keeping with the theme of a watershed as a metaphor, our quarterly review meeting has been repurposed as our Quarterly Confluence.

In short, having someone in the People and Culture Leader position has given us one, clear person who we know is always keeping an eye on all aspects of our operations through the lens of our culture and our values. We have become more consistent in the way we communicate with each other and in the way we connect with our clients and stakeholders. Our internal culture has always been strong and grounded in deeply shared beliefs, but now we have someone making sure that we are consistent across all our work, our conversations, our locations, and our messaging.

Importantly, we are preparing for a leadership and ownership transition at Biohabitats, as I prepare to step down as CEO in the coming years. Like Patagonia, Biohabitats will be transitioning to a Perpetual Purpose Trust, further reinforcing our commitment to our mission of Restoring the Earth and Inspiring Ecological Stewardship. As we move through this transition, I am relying heavily on our People and Culture Leader to help us think through that process and ensure that our plans and decisions stay true to our mission, values, and purpose.

As to whether or not hiring a People and Culture Leader instead of an HR Director is the right move for your business, you will have to evaluate against your own culture and beliefs. But I believe that any Evergreen® business, with a commitment to leading with Purpose and putting People (and, for us, Planet) First, would be a strong candidate. ‘People and Culture’ and ‘Human Resources’ are not the same thing. Language matters. It’s an important first step in communicating how you think about and value your team and the culture you wish to create and nurture in your business.

Tugboat Institute @O.C. Tanner: Let's Get a Little Better Every Day

O.C. Tanner was founded on the twin pillars of beauty and kindness, and both were abundantly in evidence last week at Tugboat Institute® @O.C. Tanner, in Salt Lake City. With nearly 100 Evergreen® CEOs gathered in person, and more joining us virtually, O.C. Tanner CEO Dave Petersen and his executive team invited us in for a close look at their extraordinary Evergreen company. It was a wonderful three days of learning, connection, and celebration.

An exemplar of all things Evergreen, but none more than People First, O.C. Tanner was an exceptional host. People First is not only the foundation of their culture and philosophy, but it is also literally their business.

O.C. Tanner was founded in 1927 by Obert Clark (O.C.) Tanner. A philosophy professor at the University of Utah, Obert believed deeply in the dignity and worth of people. The importance of employee recognition and celebration was far from a commonly accepted notion at the time, but Obert intuited its value and became an early champion, both in practice and by trade.

Obert got his start selling seminary graduation pins and class rings, part-time, working out of the back of his car. In its first 43 years, his company grew from $0 to $12M in revenues, making rings, celebratory pins and, eventually, employee service awards. Guided by his dedication to beauty and kindness as well as his commitment to creating a superior product, O.C. developed the motto that is still often repeated today; “let’s get a little better every day.”

For the next 30 years, the company evolved and grew, creating new service awards programs and extending their offerings to include recognition awards. During this time the company expanded significantly, in terms of revenue, products and services, and number of employees.

The past 20 years, under Dave Petersen’s leadership as President and then CEO, have marked the greatest period of innovation the company has known thus far, first by making the significant shift from being primarily a manufacturing company to becoming a leading software solutions company. They also built a state-of-the-art, automated distribution center to deliver complex product combinations right to the desk of the customer manager and, importantly, they created the O.C. Tanner Institute to advance the understanding of People First recognition and awards.

Today, O.C. Tanner serves over one thousand clients across 180 countries and delivers 5.3 million awards annually from offices in Salt Lake City, Canada, England, Singapore, Australia, and India. The company has been recognized as one of Fortune’s 100 Best Places to Work and was awarded the Shingo Prize for Excellence in Manufacturing. In spite of this enormous growth and innovation, O.C. Tanner remains a company and a community that is defined by the spirit and values of its founder, putting People First, pursuing beauty and kindness in all things, and staying private forever.

Our week of learning kicked off with a celebration on Tuesday evening, and on Wednesday morning, we dove into two days of workshops and presentations on-site at O.C. Tanner’s incredible Salt Lake City campus. Dave Whorton and Dave Petersen opened the two days with a Fireside Chat, in which they visited the history of the company, Dave Petersen’s personal journey to leadership, and how the Evergreen 7Ps® come to life at O.C. Tanner. Through the rest of the day and all of the following day, we were able to visit with and learn from key O.C. Tanner executives, who presented on topics ranging from Strategy Evolution, to Community Impact, to Corporate Governance, to the People First culture of O.C. Tanner. We also spent time with the Director of the O.C. Tanner Institute, who shared insights about the importance of culture to employee engagement and fulfillment, something that is critical to all Evergreen companies. Finally, we spent time each day in workshops, talking and thinking about some of the big issues we all face, including building thriving cultures in our organizations and planning for the future.

As unique, powerful, and important as it is, the value of gathering our tribe is not limited to the learning we all share when we come together. From the first evening, the energy and excitement at reconnecting with friends and peers was palpable. To honor the importance of these connections and friendships, in the evenings we celebrated our special community with two fantastic dinners, one of which was held at the Utah Olympic Park.

Standing at the top of the Olympic ski jump, many of us were humbled, struck by the courage, optimism, hard work, and tenacity it takes to become an Olympic athlete. A great many dream of it, some try for it, and only a few, extremely talented and dedicated individuals are able to make it a reality. In some ways, the same could be said of the Evergreen CEO; it is not an easy path, but when grounded in a deep belief in purpose, a willingness to work hard and stay in it for the long haul, and a steadfast dedication to making the world a better place, it can become a reality.