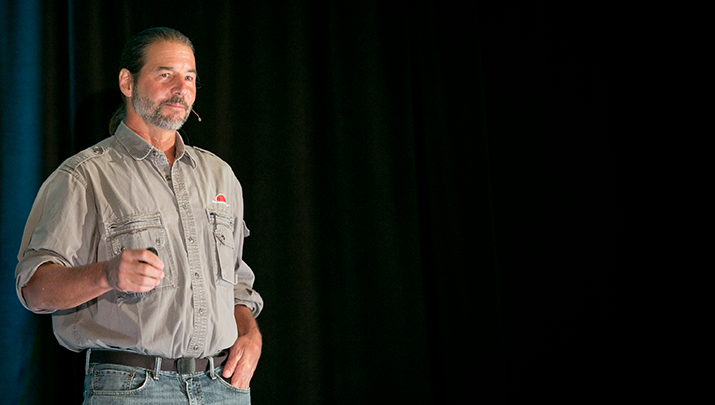

Jack Stack On Why Everyone Should Play The Great Game Of Business

At the Tugboat Institute’s most recent exemplar visit, members were able to hear Jack Stack tell the story of how he came up with The Great Game of Business after taking out a massive loan to buy out SRC from a failing International Harvester. With no experience running a company, he had to make up the rules as he went along and trust in his employees.

He quickly realized that the only way the company would thrive was if he taught the employees that the product was now the company. Understanding people hate to lose and love to win, he turned opaque company finances into an open game with rules, scoreboards and rewards. His employees returned his trust with amazing feats of entrepreneurialism that have helped grow SRC into a company with over $550 million in revenues and many successful offshoots.

What Evergreen CEOs Need To Know About Working With Millennials

I lived in my car on and off for nine months in 2009, when I was 21 years old. I slept in grocery store parking lots and spent 18 hours a day working for free in a city hundreds of miles from my home. All with the hope of starting a business in the real estate industry to fund my passion.

Does this bust any of your myths about millennial workers?

Since that cramped but productive time in my life, I have gone on to launch six successful businesses in Nashville, Tennessee. The Purpose of my Evergreen company, Aerial Development Group, has always been to empower people, sustain the planet and utilize capitalism as a force for good. I call this Excellence with Impact. We combine commitment to excellence in our products and services with dedication to impacting the world around us; we’ve sold over 290 homes, elevated 18 communities, sponsored 112 orphans in Africa and supported 12 local outreach programs.

And of the 28 people on my staff, 12 are millennials—my peers. I give them a lot of credit for our success.

Some stereotypes of millennials are based in fact. They need a lot of affirmation and attention. But with the right support they can become a major asset to your company.

Millennials are uniquely dedicated to personal development. They want to keep learning and rise within a company. Believe it or not, they are self-motivated and driven. But CEOs need to make sure they keep millennials focused on the broader mission of the company as well as their own achievements.

At Aerial, we have multiple strategies we use to manage millennials (as well as everyone else in our office). Specifically, we have a platform in place to make sure millennials are heard. Giving them time with management shows that we care about their growth as well as the growth of the company. This not only motivates them, but it also keeps our company sharp.

One tool we’ve found particularly effective is the Monday Morning Pow-Wow. Everyone has a chance to share their new ideas and suggest innovations—nothing is off the table. From assistants to executives, everyone receives equal respect in these meetings, and magic has had a tendency to enter the room during this time.

Then there’s the daily tool millennials particularly love called Align. The web-based management app lets everyone see the priorities of the company and the individual departments and then breaks down these priorities into specific tasks. It’s a nice, clear way for employees to see how everything they do contributes to the company’s goals.

We also do quarterly individual reviews to make sure everyone is working to achieve their goals as efficiently as possible. Although millennials tend to value Purpose over a paycheck, they can still be motivated by money. We always say, “We’ll give you a raise, but you have to show us why it makes sense for the company.” This is an empowering and educational exercise for all. It allows them to have some control over their rise in the company while also teaching them to think more like CEOs who understand the connection between raises and value creation.

It’s not all easy. I’ve found that I need to constantly remind my millennial employees of the big picture; otherwise they get bored and feel like they aren’t doing something with their lives. I have to show them why performing even a mundane task has meaning and contributes to the larger company and, sometimes, the world.

For instance, I recently went to Haiti to help set up an entrepreneurial program so the citizens there can create their own opportunity and won’t have to rely entirely on NGOs. When I returned, I had a meeting with my staff and showed them a video that reflects our company’s core values, why conscious business matters and how the work we all do will affect this particular project in Haiti. Through this little bit of extra effort, my entire staff was energized by my solo trip, and they feel good about staying home to keep the company going in my absence.

Make sure your Evergreen company has a Purpose, whether it is environmental or People First-oriented. This is what our generation demands. We grew up on Disney films in which the wealthy character was painted as the greedy villain every time. Millennials care deeply about the world and making it better. More than 75% of us say it’s important for a company to give back rather than just make a profit. We want our lives to affect others in a continuous and tangible way.

The Evergreen way will attract millennial clients and customers. A strong Purpose will attract and keep millennials as employees, as well. Open your doors to them. Mentor them. You’ll be astounded by their vision and capacity for change.

Your Evergreen company will be richer for doing so.

Britnie Turner Keane is the Founder and CEO of Aerial Development Group.

People First From 28 To 15,000 Stores

When Howard Behar joined Starbucks as president in 1989, the company had just 28 stores. Through his leadership, early actions and behaviors he established a People First culture and led the coffee giant’s expansion to over 15,000 stores internationally.

In a discussion with Tugboat Institute CEO Dave Whorton, Behar shares his life story and reveals how a single lesson from his dad in their family’s grocery store forged his deep-seated belief that the meaning of life is to serve others. Behar, who contends that all businesses are in the people business whether they realize it or not, shares the most important lessons from Starbucks’ growth, and what he’s learned in the years since that chapter of his life ended.

How Being Evergreen Helped Us Raise Millions To Fight Cancer

From the time I was 12, I knew I was going to be an entrepreneur. I had been running businesses of various types since I was in the sixth grade, including a student newspaper, which was shut down when the principal realized I was making money from it.

When I traveled around the world after college, I realized building a business to make money wasn’t going to be enough. My future business needed to have a strong Purpose that would allow me to give back while growing my company.

In 2007, when I was watching The Amazing Race on TV, I had an idea. I thought about how much I’d like to take part in an event like that, and I guessed other people would, too. I decided to start a business creating unique, fun events. Running had always been a passion of mine, and a few months later I launched the Great Urban Race as part of Red Frog Events. More than 150 people took part in the first run, and within a year I took it on a nationwide tour.

Until that point I had been working by myself from home. After the Great Urban Race, I brought my brother-in-law on-board to help and together we launched Warrior Dash, the first obstacle race series in the country to feature fire jumping and mud crawls. It was an instant success, selling out 2,000 spots within hours. We had pioneered a new industry.

As our company grew, we moved into an office space in Chicago complete with adult tricycles, candy machines and foosball tables. We were focused on the growth of the company but equally focused on creating a lasting culture for our employees. I decided that we would never sell the company or have an IPO — that we would embrace the Evergreen path, and with it, a better lifestyle for all of us.

Our customers were having fun at our events, and our business was growing in size and profitably. With our success, I felt it was time to start giving back, but I wasn’t sure which way to go. We partnered with St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital locally for one of our events in Denver, and it was then that I learned about their incredible, life-saving work. I fell in love with their mission. They were providing free cancer treatment to any child from around the world and producing groundbreaking medical discoveries. I knew we could make a major impact on the organization and was determined to figure out how we would incorporate them into each of our ventures. During the first few years of our partnership with St. Jude, we raised more than $5 million for the hospital through methods such as offering ticket buyers a chance to add on a donation to St. Jude.

A couple of short years later, I surprised the whole company by flying everyone to Memphis, St. Jude’s home, for our annual retreat. Touring the hospital and seeing kids who have to go through daily treatments affected all of us. That was the moment we, as a team, committed to something bigger. In 2013, we pledged to raise $25 million to help build and equip the St. Jude Red Frog Events Proton Therapy Center, the first center of its kind dedicated solely for child patients.

The St. Jude Red Frog Events Proton Therapy Center officially opened in December 2015. With proton therapy, doctors can precisely target cancerous cells while sparing nearby healthy cells and organs. Young children will no longer be subject to unfocused, high doses of radiation that can damage their developing brains.

Although we don’t require it, we encourage all our racers to fundraise for St. Jude. At each domestic Warrior Dash, participants who raise more than $300 receive access to a VIP area, complete with showers, a private tent and gear check. They receive extra benefits for giving back, and we donate all of that VIP package money to St. Jude. We also produce and host an annual Mardi Gras-themed fundraiser in Chicago, Beads for Hope, where all revenue goes directly to the hospital. We constantly work to raise awareness about St. Jude in all of our communications and events.

In 2012, the year before we made our big commitment, we launched Firefly Music Festival in Dover, Delaware. We knew it was a risky industry to enter and expected the inevitable losses we had in the first year. Word about our festival spread, and in Year Two we more than doubled in size with 65,000 attendees. I remember being on stage during the Red Hot Chili Peppers headline set with some other Red Froggers and exchanging quiet high fives. Today, solely through Firefly, a type of event that typically does not produce mass fundraising opportunities, we’ve raised nearly $200,000 for St. Jude through on-site donations and donations during the ticket-buying process.

We’ve already raised $13.5 million in three years towards our $25 million target. Because we stand on our own, we can take risks and keep our dedication to St. Jude at the core of our business. We regularly host visitors from St. Jude at our events and learn about the patients St. Jude treats. They keep us inspired. Our entire team will be going back to the hospital later this year, and we are well on our way to meeting our donation goal by our target date of 2022.

Joe Reynolds is the Founder and CEO of Red Frog Events.

Being Evergreen Helped Me Serve A Broader Purpose

F.K. Day and his brother Stanley Day started SRAM Corporation in 1987 with a passion for biking and innovation. The early years were not easy — the Days learned some hard truths about private equity backers and the importance of cultural fit when making acquisitions. Eventually they found their stride, and SRAM became a leader in high-end bicycle components, and a consummate Evergreen company.

But F.K. ultimately would have an even larger impact on the world. Moved by the 2004 tsunami disaster in Indonesia, he wanted to do more than send checks to relief funds — he was compelled to provide tangible aid. He soon found that something as simple as a single bicycle could change a family’s future for the better. Using Pragmatic Innovation, he took what he knew about high-end bikes and created an efficient, scalable model for producing low-cost, rugged bikes. The end result: World Bicycle Relief, which provides bicycles to students, health-care workers and entrepreneurs throughout Africa, South America and Southeast Asia.

Why Do So Many Evergreen CEOs Revere A Guy Who Fixes Diesel Engines?

Every fall, Tugboat Institute co-hosts its second major event of the year called the Tugboat Institute @ Evergreen Exemplar Visit. Last week, I traveled to Springfield, Missouri, along with 50 other Evergreen CEOs to learn about Jack Stack’s version of open-book management called the Great Game of Business (GGOB).

Why does his management approach resonate so deeply with us? Perhaps it is GGOB’s emphasis on People First and Pragmatic Innovation. Or perhaps it’s just the openness, honesty, empowerment and fundamental goodness that the system promotes—an echo of the employee relationship that many Evergreen leaders are working to build with their teams.

Stack doesn’t have an MBA or even a college degree, but he has been a gleeful student of business all his life. Like everybody’s favorite mad scientist, he’s been running experiments at his laboratory, Springfield-based SRC Holdings, best known for its skill at remanufacturing industrial engines.

In 1983, Stack and a few friends and fellow SRC employees put up $100,000 and borrowed $9 million at an 18 percent interest rate to buy the then-money-losing firm from dying International Harvester (IH). From the start, Stack took a radically different approach to managing SRC—one born of desperation, not genius, he insists. The day after the acquisition closed, Stack and his management team realized that they had forgotten to negotiate an IT agreement with IH. IH had turned off all their computer systems and access to all of their data from customer orders to payables.

So what did he do? He called all of his employees into the break room and line by line rebuilt their income statement and balance sheet together on a huge whiteboard. Everyone had to pitch in to help fill out the information. That “huddle” became the beginning of a weekly meeting with all employees to share the detailed financial information of the past week and to go over forecasts. They celebrated wins and addressed shortfalls.

He begged everybody—even the janitors—to help SRC get to profitability and to pay off the company’s bank debt. They didn’t have much time. He saw that few people understood the financials, so began training everyone on the team on the “rules of business,” using sports as the metaphor. How can a baseball team take the field if they don’t understand the rules of baseball? And, why will the team members engage if there isn’t a “scorecard” that shows whether they are winning or losing? And, why work hard and take the risk of suggesting improvements if they don’t have “a stake in the outcome?”

These three gamification ideas working together—teaching the rules of business, providing a clear scorecard and sharing in the success of winning—are the basis of the Great Game of Business.

Today, SRC’s equity is valued at hundreds of millions, the company has paid out over $100 million to retiring former employees, and thanks to its employee shareholder program, everyone in the company continues to benefit from SRC’s profitable growth. The 28 percent annualized return SRC has delivered over the past 33 years is superior to Berkshire Hathaway’s. More importantly, when we toured his facilities and watched his son lead a huddle, it was clear that people love working at SRC.

With the help of journalist and author Bo Burlingham, Stack has been hammering the drum of his version of open-book management for decades. Their 1992 book, The Great Game of Business, is a classic that every entrepreneur should read. Stack happily shared his wisdom with us over two exciting days, with Burlingham contributing a pearl of wisdom or a dig from time to time. From the first night we all gathered in the lobby of the Doubletree to learn about the great game, it was clear this was a group eager to play.

Like a lot of other Tugboaters, I was electrified when I first heard Stack tell his story, at Tugboat Summit in Sun Valley last year. I raced back to my bookkeeper and announced grandly that we would henceforth adopt open-book management. “What is it?” she asked. “I’m not exactly sure, but I want to try it,” I said. “Does it involve opening the books?” she asked. “Yes,” I said. “Well, we have less than $1 million in sales and three employees. So your idea is giving me a panic attack.” (Did I mention that I am married to my bookkeeper?)

Inspired by Stack’s early days, I experimented. I hunted for small ways I could give my employees a taste for the highs and lows of entrepreneurship. Like any company attempting to make a go of open-book management for the first time, we fretted over whether the system would fuel conflicts and jealousies.

It’s all been a bit clumsy at times, but my small team has embraced the game. I’ve seen them get excited about the rules of business and our numbers and feel the business buzz.

The Great Game of Business is a constantly evolving process, though. Did I come to Springfield with questions? You bet. Boy, did I get answers. I realized I was making this more difficult and less fun than Stack would have. First, you have to train people. Second, you have to get them working and interacting as a team. Stack and GGOB team member Steve Baker taught us that to make it work, you have to overcome the enormity of the challenge by making a game of it—literally.

In fact, Stack strongly encourages “mini-games” designed around 90-day goals that attack specific issues or opportunities in the business. Say the busboys in your restaurant chain carelessly throw away spoons to the tune of $10,000 a year. Create a “save-the-spoons” mini-game and reward the players with half of the gains through a progressively better set of gifts. For example, give a nice monogrammed mug to each busboy for hitting a modest goal and a French press for doing much better than that. Or suppose your bicycle manufacturer built two dozen folding bikes three years ago that are now unsold and unloved? Create a “brilliant mistake” mini-game to quietly usher the oddballs out the back door in steeply discounted private sales to cyclists with a sense of humor.

Our group was inspired and moved by the presentation. When we asked Stack what we could do to thank him for his hospitality and gift of his learnings he said, “Just buy me a beer the next time you see me. A Miller Lite would be preferred. And, care for your people and your families.” That’s the kind of guy Jack Stack is.

Stephane Fitch is the Founder of FitchInk.

What Evergreen Means to Me

At the Tugboat Institute, we live our Purpose: To build a trusted community of Evergreen CEOs and executives who share with each other their inspirations, best practices, unique insights and support. At our past Tugboat Institute Summit, we asked several of our members, “What does being Evergreen mean to you?” We found their replies inspirational and are thrilled to share the gift of their answers here with you.

Atlas Shrugged: Amy’s Empowers

After college, the ice cream company where Amy Simmons worked was sold to a new owner. Overnight, the culture changed. Because of that experience, she vowed to build a better business, one that sold delicious products but also provided a great work environment. Thirty-two years later, Amy’s Ice Creams is a Texas institution known for both its super-premium award-winning ice creams and its dedication to putting People First. She’s also turning the idea of successful enterprise on its head.

In her Tugboat Institute Summit 2016 talk, Simmons shares her passion for creating an empowered culture built on training, trust and financial and business literacy. The result: a thriving, high-performance, happy workforce that pays it forward in their families and communities.

How My Scars Led Me To The Evergreen Path

My journey to creating an Evergreen company began at MCI. Although it was a multibillion-dollar company, it operated like a startup, competing against industry giants such as AT&T in a David vs. Goliath environment.

It was the perfect starting point for me. My father, a career FBI agent, had told me that I was unlikely to ever join the bureau. But a friend of his, who worked in pharmaceuticals, told me I’d make a great salesperson. MCI gave me the chance to hone my sales skills, but after a few years I realized that to truly grow into a leadership position, I’d have to move beyond my MCI cubicle.

So when the opportunity arose to join a startup that was building an internet billing company, I jumped at the chance. This was 1995, when people were still skeptical of handing over their credit card details online. We had an innovative third-party solution, and our company, iBill, was an instant hit with revenues to match.

The company was a balance sheet success and grew to be a fairly large business, but when it was sold in 2002 after the dot.com crash, I didn’t have the big payoff that I’d dreamed about and felt the whole experience had been unsatisfying. Amazingly, although I was a founding member of the team — I had provided seed money and hired the team — I had less than 1% on exit.

It came as little surprise to me that two years after InterCept bought us, our company essentially went out of business. The experience was a lost opportunity. We could have been PayPal, but it never came to fruition.

The problem was, finances aside, we were not building a sustainable company. Instead of focusing on careful growth, we paid absolutely no attention to our customers and served every single dark corner of the internet. To keep up with the explosive growth of the internet, we made bad decisions in every area of the business — strategy, HR, execution, clients, etc. The upside: I learned a lot about a growth-at-all-costs mentality.

The company’s demise left me with plenty of scar tissue. It’s not a company I look back on fondly. I was determined to make sure the mistakes we made wouldn’t go to waste.

In 2007, we launched 3Cinteractive, a mobile consumer engagement platform that helps our clients build more profitable relationships with their consumers. To avoid past mistakes, I built my company around three main principles.

First, it would be sustainable. The business would take on little debt and have few investors. My partners and I would own it and be able to make all of the decisions.

Second, I wanted to focus on doing something important for world-class clients. At iBill, we had taken on any client we could get (embarrassingly most of them ended up being porn sites) rather than making sure we had a core group of reputable business partners. Now we proudly call Walgreens, Disney and Best Buy our clients.

Finally, and most important, I wanted to support and nurture my employees. After iBill’s sale, it was the staff that lost out the most, and I wanted to build a learning culture where I could work with great people and treat them fairly.

It hasn’t all been smooth sailing at 3Ci, and that’s when our principles have mattered the most. Bad experiences, market downturns, ill-advised hires and miscalculations could have killed us if we had not lived by our principles. They have guided our decision-making and helped our company achieve greater success for all of us.

They also have given voice to our employees and stakeholders at important junctures. For example, when we were deciding to take on modest debt, our employees rightly questioned how this move would create customer value and opportunities for greater returns, and not put our business at unnecessary risk. That debt has since been paid back.

We encourage these kinds of discussions because they mean our employees have a sense of ownership and are growing along with the company. When I see our employees with stacks of books on their desks to further educate themselves, I love their aspiration and strive to help them in every way I can.

The lessons I learned from my first failure have helped build a strong culture, and we hope that by continuing to follow the Evergreen path, we will make good decisions and build a long lasting, principle-driven company together.

John Duffy is the Founder and CEO of 3Cinteractive.

After Success: What’s Next?

For Evergreen entrepreneurs, building a company that will last more than 100 years means taking great care with transitions such as transferring leadership within our businesses and transferring wealth, values and stewardship within our families.

In his Tugboat Institute Summit 2016 talk, Dennis Jaffe of Wise Counsel Research encourages business owners to treat their children like partners instead of subordinates — and to speak frankly about money. By fostering a spirit of transparency, engagement and shared learning, he says, Evergreen leaders will inspire a future generation of courageous business innovators.