Doing the Impossible

Rather than watch his colleagues lose their manufacturing jobs at International Harvester during the bleakest days of the 1980s, Stack came up with a crazy idea: Why not lead a worker buyout of his division of the company? Stack vowed that if given the chance, he'd create a transparent workplace where the financials were not only open to inspection, but a mandatory part of employee training.

It took years for the new company, SRC Holdings, to get on its feet but by creating a strong culture around his model of Open-Book Management, Stack was able to create a sustainable business. His employees understand, and are invested in, helping make the company as profitable as possible. His technique is one that many Evergreen business leaders will want to embrace.

Inspired By Ancient Traditions To Build A 100-Year Company

I found inspiration for my Evergreen business in Kyoto, Japan, among gold-leaf artists and geisha.

As an overzealous intern during my time at Harvard Business School, I had tested too many skin-care creams on myself and contracted a case of acute dermatitis. The only thing I could use on my skin was Aquaphor, which left a greasy residue, but blotting paper from Japan mitigated the shiny effect.

During my travels, I found myself in Kyoto, where I learned that the papers were the byproduct of gold-leaf manufacturing and that geisha had discovered their usefulness. When I met these women, I was immediately enchanted by them. Their white makeup didn’t hide their skin like Western makeup does; instead, it enhanced every possible flaw. But of course there weren’t any flaws, because the geisha had perfected the art of skin care. Their products were all-natural, from the days before cosmetic companies put questionable ingredients in lotions. I went to their apothecary, bought a bunch of geisha-recommended ingredients and started using them myself. Within eight weeks my skin recovered from the acute dermatitis that had plagued me for years, and I knew I had found my calling. I planned to create a skin-care collection — based on the timeless rituals that the geisha honed over centuries.

I started building Tatcha out of my one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco. As an entrepreneur in the heart of the tech world, I was tempted to go the venture capital route. All around me, I saw friends taking millions of dollars in investment money, selling out quickly and reaping the material rewards of a quick exit.

Given my long-term goal, though, that didn’t feel right to me. I was building my business based on my respect for these ancient traditions. I wanted to build something that would last 100 years.

I started like many small-business owners, using credit card debt and working multiple jobs for seed capital. When that ran out, I sold my furniture and engagement ring and worked four jobs. When that again ran out, I borrowed money from family and friends. At one point I considered selling the company despite the amazing traction we were getting, because I couldn’t figure out a financing strategy that would give us the runway and independence to create the brand in a way that would stay true to its vision. Thankfully, it was at that time that I met my business partner and future Tatcha president, Brad Murray. He came from the private equity world and has managed to keep Tatcha majority owner-operated while still securing the capital necessary to grow.

Our financial independence has allowed us to make decisions we wouldn’t have been able to make if we had fast money behind us. For example, as part of our purpose, we wanted to make sure that our business had a built-in charitable aspect, so we partnered with Room to Read. Every full-sized skin-care purchase from Tatcha or any of our retail partners sends an incredible girl to school for one day through Room to Read’s fund for girls’ education in low-income countries. Investors might have frowned on that diversion of funds, but I’m proud of the fact that in the first 18 months of our partnership we have raised enough for 1,000 years of girls’ education.

We don’t spend money like Silicon Valley startups typically do. Our offices are nice but not fancy. Until two years ago we were based out of my house, which was often bursting with products ready to ship. We spent on real estate only when it became completely necessary. We focus our spending on things we think are the most important, like product development and customer service.

Brad and I have not taken true salaries yet. We’ve opted to invest every dollar back into the company. Every year, I consider paying myself in the next year, but then I think about what that money could do back in our business, and I hesitate to make that change.

Sure, it would be nice to own my home and have a fancy new car — but those things matter less to me than building equity in my own company. Our hard work and frugal ways are paying off. Between 2011 and 2014, we grew over 10,000 percent. We had revenue of $12 million in 2014. We are on track to grow 50 percent in 2015 and expect to keep this pace up next year. This year we also debuted, at 21st place, on the Inc. 5000 list of the fastest-growing companies in the U.S.

I look at companies in Kyoto and I see how they’ve thrived over 14 generations. Through thick and thin, they’ve become part of their community. What I’m learning is that if you want to be around for 100 years, it’s best not to benchmark companies that are going to exit in five. Instead, you surround yourself with the kinds of people who share your values and you build a culture of sustainability. That’s truly the best way to grow for a century or more.

Victoria Tsai is the Founder of Tatcha.

How Diversification Helped Our Business Survive And Then Thrive

A lot of companies focus on doing one thing well. We think an Evergreen company needs to do several things well in order to succeed over the long haul.

But multiple business lines and far-flung geographic markets were not something we considered in the early days of our company. In 1998, San Francisco was teeming with young dot-com companies. Money was flowing, and workers were sick of unhealthy foods littering their offices.

Delivering fresh fruit to offices was a novel — yet refreshingly simple — concept that allowed The FruitGuys to grow quickly. Our first delivery was in 1998 by scooter; by 2000 we owned five delivery trucks. It felt like everyone in the city at that time was enjoying our fruit around the conference table. We even had a secret knock to gain entrance to Napster. That year, we hit $1 million in revenues.

But in 2001, the bubble suddenly burst. We were showing up to offices that were closed and had posted eviction notices. We were devastated when we found a chain around the door of one high-flying Internet company; it owed us thousands of dollars.

Things spiraled from there. We laid off 50 percent of our staff, and we lost half of our customers. We asked the remaining customers what they needed in addition to fruit. They said they wanted dairy service for their coffee and cereal needs, cut-fruit platters for the partner meetings, and bagels and other baked goods. Very quickly, we shifted gears. In addition to providing offices with fruit, we became their corporate caterers.

And we survived. In fact, we got back our footing and started once again to thrive. Over time we grew from being a regional office delivery service to a national provider of fresh fruit. By the mid-2000s, we were producing a few million dollars in revenue and growing. Ex-dot-com workers who moved from the Bay Area reached out to us and we started shipping fruit crates around the country. We continued to service the Bay Area with our expanded products.

Then 2008 hit. Our country went into a recession, and we were hit hard, losing approximately 25 percent of our revenue. We had a company vote — we had to decide if we should move forward with layoffs or reduce our salaries by 25 percent for 90 days to see if we could boost revenues during that period. Our staff voted on the latter, and we hit the streets trying to find new ideas. Out of that desperation, we again moved into another ancillary business.

The USDA had just piloted a program to provide fresh fruit to schools. I rented a car and drove all around California educating schools on how they could apply for grants for free money. I got a couple schools to sign up for it — and pay us to provide the fruit. This became a new line of business.

Today our school service accounts for approximately 15 percent of our revenue. We serve roughly 200,000 pieces of fruit every week to elementary students; the majority of these kids are part of the free and reduced meal plans. This was a necessity for our business to survive the last big bump in the road, but it also feels good to be making an impact for these kids who often don’t have access to fresh fruit. Our program is aligned with nutrition education, and in a few cases we provide on-site assemblies to teach the kids why eating healthy is important.

We now have 125 employees in nine different states. We serve thousands of companies with our fresh fruit every week. We’ve been growing our revenues 20 percent year over year for the past few years.

We will always sell fresh fruit. After all, we are The FruitGuys. But adding nuts, school programs, workshops and gifts to our business mix provides multiple layers of padding that protects our company from the ups and downs of an ever-changing environment and keeps us fruitful.

Erik Muller is the President of FruitGuys.

Unexpected Lessons From Iraq: Effective Meetings

Meetings are an oft-bemoaned part of life in corporate America: too long, too many and mostly seen as simply a waste of time. But in today’s challenging environment, how your organization meets is crucial to whether you succeed or fail.

As information speeds around the Internet virally, problems crop up more quickly than ever. To avert disaster, companies need to be nimble enough to deal with those problems quickly and efficiently.

A product mishap or a disgruntled consumer can tank your brand overnight. A crisis or natural disaster on the other side of the world can disrupt your carefully planned supply chain. If you’re a growing startup, a competitor can come out of seemingly nowhere, threatening your business.

But in contrast to the fluid dynamics of our operating environment, most of our meetings are legacy concepts — the way things have always been done. (Daily sales meetings here, standing weekly meetings there, monthly reviews, annual boring corporate events, etc.) Furthermore, we don’t even view these forums as an effective place to get business done — we rely instead on sidebar conversations, war rooms to address a short-term crisis and endless one-on-one or smaller group meetings. So it is time to rethink the meeting to address the realities of business today.

Matching the speed of the 21st-century operating environment

I experienced this disconnect in what you might consider an unexpected environment: Iraq in 2004. When confronted with the challenge of a highly networked adversary, our standard operating processes and meetings were woefully inadequate.

Like many businesses, we conducted meetings with the most senior leaders to discuss high-level strategies; then each leader passed on information and guidance down to their subordinates, who would in turn pass it on to their subordinates in a series of smaller and smaller meetings that took nearly all day.

Not only were these meetings time-consuming, but they created a kind of game of telephone that filtered out more and more context and intent along the way. The message that finally got to the operators on the ground could be very different from what senior leaders initially intended. Even worse, by the time the information reached the folks on the ground, the problem had often changed; the enemy had moved on, the target was irrelevant and we were two steps behind.

Corporate America faces similar challenges. Those on the ground and closest to the problem have great operational context (whether that’s how a product is doing, how customers are reacting, etc.). But by the time that information has made its way up the chain of command, senior leadership has made a decision and that guidance has been filtered back down — it can be too late. Running things up the hierarchical flagpole and waiting for garbled direction to make its way back down is simply too slow and error-prone of a process for today’s world.

Those flagpoles are not the only issue — most teams in today’s business environment are incredibly siloed, and tend to focus only on their piece of the problem. However, almost all challenges organizations face today are complex and interdependent; no one team or single person has all the answers, yet cooperating across geographic distance and functional groups can be difficult.

Learning as an organization

So what’s the solution? In our view, organizations need to be incredibly adaptive, agile and collaborative to meet 21st-century challenges and opportunities. Information needs to be shared widely and individuals need to be empowered to act quickly on their own.

Thus, the rate of organizational learning is critical. Businesses need to learn in real time. Intelligence needs to come from the bottom up. Opportunities need to be seized, challenge mitigated and the collective wisdom and experience of the entire team harnessed.

To achieve this, we have to create continuous organizational feedback loops that are much faster than the traditional hierarchical processes. To open these loops, we must tear down flagpoles and silos, and harness the perspective and knowledge of all teams and functional groups within the organization at the same time.

Managing that enterprisewide learning process requires discipline, focus, transparency and accountability in how the organization communicates and makes decisions. One method to create this may surprise you — a very large meeting. We call it our “keystone forum.”

The power of the keystone forum

The keystone forum is a single meeting for everyone to hear the same information and context. This provides the transparency, information and guidance necessary to empower people to action outside of that meeting and creates an organizationwide shared conscience that is unique in business today. We have found that the concept, similar to the “business performance review” meeting popularized by Alan Mulally at Ford, is incredibly successful.

What differentiates a keystone forum from any other large meeting is the discipline, standards and thought that go into its creation and execution. Everything from the agenda to the leadership’s behavior must be incredibly intentional and purposeful — otherwise it will degrade into just another ineffective meeting.

Attendance, agenda, frequency, technology, follow-up and interaction are crucial to making a keystone forum work. In Iraq, we met every day for 90 minutes and almost 7,000 people joined the call. We installed state-of-the-art technology to allow video-teleconferencing for more personal connections. We crafted a purposeful agenda — and stuck to it. It wasn’t just a “report up”; it was truly designed to be a “report across,” focused on generating cross-talk and sharing context to connect the efforts of teams that otherwise wouldn’t interact.

This worked well in the military, and our clients, like Intuit, Scotts Miracle-Gro and others, have also found success with their own versions of the keystone forum. Each forum looks different at every company — some are monthly, some weekly, some have 100 participants and some have 500 participants.

They were all designed and customized to fit the cadence and needs of their respective industries, but all of them have elements in common:

- A review of action items from the last meeting

- A review of key business metrics

- Overview and/or reminders of strategic context from the senior leader

- A sharing of new information about the external and internal operating environment (competitors, regulations, political/social dynamics)

- Updates or lessons learned from teams and functional groups since the last forum

- Documentation of action items, assignments to owners and commitment to follow-through engenders effective execution and results and ensures accountability

The importance of transparency and leadership behaviors

All successful keystone forums have another thing in common: disciplined personal and digital leadership behaviors. When running a large forum, it is essential that both the leader and the presenters model certain behaviors, especially if the meeting is virtual.

For the leader:

- Clearly communicate and reiterate the main intent and priorities of the organization. It may be obvious to you, but it’s probably not to those lower down in the organization.

- “Thinking out loud” or walking through your thought process is essential so others can see how you make decisions and what’s important to you.

- Drawing connections between presentations is also essential — everyone needs to see how disparate efforts come together, and it’s your job to connect the dots.

- Encourage open dialogue, and even go as far as planting a dissenting opinion to model for others that it’s OK to challenge leadership’s views.

- Empower presenters and give them confidence. Know everyone’s name and ask questions, even if you may know the answer. Always ask for their and others’ opinions.

- Remain calm when receiving bad news — getting this feedback is essential for organizational learning, and the organization will mirror your behavior.

All of these behaviors may feel uncomfortable at first, but they are critical to setting the right tone for the sharing and collaboration that needs to take place.

Ultimately, transparency is essential to the successful execution of a keystone forum — without it, the meeting becomes a good-news-only cheerleading session where real issues aren’t discussed and decisions aren’t made. That might mean a big adjustment in personal behaviors and willingness to be vulnerable in front of a large audience, but it will inspire real discussion around what went wrong and how to avoid similar mistakes in the future.

With time, the keystone forum should help your organization build trust, communicate better and more efficiently, empower decision-making and rapid execution at all levels of the organization, and arm you and your team to face the challenges of the 21st century.

David Silverman is the founder and CEO of CrossLead and a former U.S. Navy SEAL.

Prepare for the Day You Step Away

Leadership succession for founders of Evergreen companies.

There are so many ways for CEO succession plans to go wrong. Sometimes the old CEO is not really ready to let go or the new CEO isn’t properly prepared to take the reins. There can be factions; there can be mutinies. Missed communications and hurt feelings can set a company back for months or crater it altogether.

I like to think that at RSF Social Finance, we got it right. Based in San Francisco, RSF has been a direct lender to social enterprises for more than 30 years. Our assets have grown over 40 percent in the past three years to $170 million, and we have made nearly $300 million in loans to 240 organizations.

I took over as CEO in 2007 after our co-founder, Mark Finser, decided to step down.

Before I started at RSF, Mark had run the organization since 1991. That’s 16 years with one leader. We’d been very successful — those were big shoes to fill. Watching the way Mark handled the transition taught me so much about being a leader and how to pass a company on to the next generation.

Succession is an especially important issue for Evergreen companies. We aren’t building companies for a quick sale, we are building them for the long run. At some point, you’ll have to hand your company over to someone else. That person might be a family member or a trusted employee or even someone from outside the organization.

Here is what I learned as the “new guy.” I hope there are a few insights that will help you, the founder/CEO of an Evergreen company, to step back when the time comes, to identify and recruit a great new CEO and to create the conditions for your enterprise to continue to thrive.

I am not saying we have 100 percent nailed it at RSF, but we have worked extraordinarily hard at each stage, and I now see — eight years later — how it’s possible for succession to be a process that brings tremendous personal growth and many other benefits for the founder, the new CEO and all the stakeholders of an Evergreen company.

Start internal preparation years ahead of time, if you can. In 2002, Mark began a series of retreats meant to strengthen RSF’s internal culture. It was important to him that the people in his organization operated from a place of deep trust and respect toward each other. By building on the collaborative capabilities of our organization, he strengthened the team and prepared them for the day when he would step away. If you get the whole organization to hold and cherish the company’s core values, you’ll have a better chance for a smooth transition.

Trust your instincts. Once you get broad support for stepping back (Mark is still our board chair, and we continue to work actively on a range of things together), then trust that you made the right choice for the new CEO — even if that person doesn’t fit your initial hiring criteria. I did not have a pedigree banking background. I was 38 when I was hired — too young for some board members. And they were hoping to hire a female CEO. But Mark and the board saw something in me that required them to let go of their preconceived ideas and trust their instincts instead.

Prepare your key clients/customers. Make sure they understand, well ahead of time, why you’re stepping back and why you have confidence in the new person. Attend the first round of meetings with these key clients if that is appropriate. Check in regularly with the new CEO to make sure you have the right feel for how much of your presence, if any, is needed. I remember many meetings early on where Mark supported me in the presence of key clients, and it really helped kick off those important relationships and build my confidence.

Allow the new CEO to make mistakes. Two months after I joined RSF in 2007, the Great Recession started. Small banks were folding left and right. I witnessed a lot of irrational behavior, and I was scared about what might happen on my watch. During this period I kept putting in place ambitious growth targets that became unrealistic relatively quickly. Mark tried to help me avoid this trap, but ultimately let me plow forward — which was great. We’ve done well since then, but that was a mistake I won’t make again.

Keep it light. In the frenetic world of business and finance these days, it’s easy to take yourself too seriously. As a founder who is providing a range of support for the incoming CEO, try to keep your sense of humor. Don’t let the new CEO stay in a constant sales mode or feel the need to continue interviewing for the job. Get him or her to slow down and even be vulnerable. My dad used to coach me in baseball, and one of his best pieces of advice was “You’re gripping the bat too tight.”

Remember: As an Evergreen CEO, you’re not building to flip; you are building a cathedral. And this takes a different mindset and a different approach to leadership altogether.

Don Shaffer has served as president and CEO of RSF Social Finance since 2007.

Why You Should Make It Easy For Employees To Leave

Don’t invest in finding ways to make people stick around. Just make it easy for them to leave. That is the best retention strategy and it is pretty simple.

It may seem backward. While companies everywhere spend a great deal of time and money creating employee-retention strategies, I’ve found you can actually build a happier workforce by focusing on the opposite. I co-founded Call-Em-All, a group calling and texting service, in 2005. It was important to me to build a staff that would be as engaged and energetic as possible. Disengaged employees? Raise your hand and opt out. We’ll help you on your way.

Because we don’t want to retain the wrong people, the freedom to walk away is deliberately built into our compensation strategies. Take our 401(k) plan, for example. Employees are 100 percent vested in the plan right away. From day one they can take advantage of our 6 percent dollar-for-dollar match. Our profit-sharing plan was built with the same goal in mind. The last thing I want is an employee hanging around waiting until bonus time to leave. I’d rather say, “Take what you earned and find another job before you sink the rest of us with you.” That’s why we give our profit-sharing bonuses quarterly instead of annually.

Of course, we try to hire smart right off the bat. One of our key competitive advantages is having a talented, engaged workforce.

To get here took some effort. First we had to define our culture as written in our manifesto, live up to it and then hire to it. Once everyone was on board, we developed a wolf-pack mentality, which is almost self-selecting. The wolf pack says we are not going to let anyone into our environment who doesn’t pull his or her weight and doesn’t fit. I owe it to my employees to bring in people who are worthy of working with them, so I am personally involved in every hire. We have an intensive recruiting and interviewing process. Good hiring is the No. 1 way we defend our culture. You want an employee who embraces the company’s values, not a functional, transactional employee. Does this person approach work in the same way we do? Will this person bring passion and energy to the company? Could I disagree with this person? How would he or she handle that? If the answer to any of those questions is negative, then regardless of their capabilities, we do not hire them.

Sure, it can be difficult to find talented employees who fit into our culture. And sometimes it’s a bitter pill to give someone a bonus for not sticking around — but both of these beat the price of retaining a disengaged employee. Although we have a great culture, it is not permanent and it is not impenetrable. One of our first employees, for instance, worked with us for five years. I still respect her, but as we grew and brought in more people, she had to share her responsibilities and ownership with her peers. She struggled to change as the environment around her changed. It affected not only her performance but also the performance of those around her.

After she left, it was like a breath of fresh air. However, we still wanted to do the right thing and give her time to find another job; we paid her three months of compensation and I also personally offered to serve as a reference for her.

We are big into energy here and believe that one person’s bad energy can impact the whole company. People had to work harder to make up her workload until we found someone else, but they were more than happy to do it. There was no longer anyone draining their energy.

That said, I don’t immediately get rid of people who are no longer engaged in their job. I encourage them to talk to me so I can try to find a way to get them re-energized. I tell my employees: If you see something else here you want to learn more about, raise your hand and do it. One of our customer service team members told us he wanted to learn about the technical side of our product. We looked for places to let him get a taste of the work and to test him. Each time he liked it and was able to do more. Now he is a liaison between our customer service and engineering departments. He plays a crucial role that saves us time and resources and is taking his first programming class. It is a happy ending for all of us.

Brad Herrmann is president and co-founder of Call-Em-All.

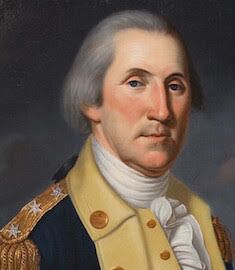

What George Washington Can Teach Evergreen Entrepreneurs

The entrepreneur’s life seems to involve endless toil and anxiety punctuated by the occasional success and, sometimes, an hour of cheerful distraction. That’s how it is for me, anyway. So when I strolled into a primitive flour mill at George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate in Alexandria, Virginia, one evening in October, I thought I was in for the distraction part of my chosen field.

I assumed Washington’s famous plantation would serve as a mere backdrop for the intensive two-day leadership workshop the Tugboat Institute set up for us. Hell, what could a wealthy ex-president in a powdered wig possibly teach a bootstrapping tech-savvy modern businessman like me?

I soon had my humbling answer: a lot.

Washington was, in fact, a vigorous entrepreneur and innovator. The lessons he learned managing his business affairs at Mount Vernon helped win the Revolution and shape the world’s idea of democracy and free enterprise. Yeah, Washington would have been a fabulous mentor.

By the way, he didn’t wear a wig. Or chop down a cherry tree, sign the Declaration of Independence or use wooden teeth. He was fortunate, sure. Washington’s family owned land and slaves and his father, Augustine, successfully farmed tobacco. Yet Washington’s life was full of challenges. When he was just 11, his father died. Washington’s uncles didn’t provide him with a formal education. In fact, Washington took his first job at age 15. A relentless reader, he was self-taught, and expected the same of the others he was leading. He believed a person can control how prepared he is for success, but not success itself. Like many of the greatest modern entrepreneurs, he had no college degree.

But was he Evergreen? Would he have nodded knowingly at the Evergreen 7 Ps? I think yes.

Purpose. After eight years leading the Continental Army to victory — Washington did it without pay — he formally handed back to Congress his commission as commander in chief. In London, George III asked the American-born painter Benjamin West what Washington would do now that he had won the war. "Oh," said West, "they say he will return to his farm." "If he does that," said the king, "he will be the greatest man in the world." Washington would repeat this act by serving as president of the United States for two terms and returning to his farm. Unlike most other revolutionary leaders — Napoléon, Stalin, Cromwell — Washington walked away from power twice to serve the public good.

Perseverance. Washington understood that perseverance was in itself the key to victory. During the eight years of the Revolutionary War, he lost more battles than he won. Through seven winters, he never left the Continental Army’s encampments, even during the famously frigid winter of 1777 to 1778, when he and his men trained and suffered at Valley Forge, 20 miles north of Philadelphia. Throughout the war, he avoided a single climactic battle that could have wiped out his army — until his decisive win at Yorktown.

People First. As a battlefield general, Washington learned (after many defeats on the battlefield) to listen carefully to his lieutenants — unlike his British counterpart. The habit stayed with him as president, when he relied heavily on the advice of brilliant (and often rival) cabinet members like Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson. And yet he owned hundreds of slaves. “People often ask us if George Washington was kind to his slaves,” said our Mount Vernon tour guide. “The answer is that there is absolutely nothing kind about slavery.” That said, Washington willed that more than 100 of Mount Vernon’s slaves be emancipated upon Martha Washington’s death — an act that no other slaveholding president, not even champions of human rights like Jefferson and James Madison, repeated.

Private. The notion of taking private ventures public was gaining steam in Washington’s day. The Philadelphia Stock Exchange was founded in 1790, and Washington did form a joint equity enterprise to improve navigation on the Potomac — the investors’ capital went to build canals around waterway hazards in the river, benefiting all. Yet Washington kept his Mount Vernon enterprise private. And he never indebted it so severely that lenders could pressure him for control.

Profit. Washington was intensely mindful of profits and always wanted to maximize the value of what he produced as markets changed. Though he had to abandon day-to-day management during the Revolution and later as president, he constantly wrote letters to his managers at Mount Vernon inquiring as to the farm’s operations and profitability. He invested in thousands of acres of land around the country, and he was arguably the wealthiest president in U.S. history.

Paced Growth. Washington sought opportunities for paced growth even in the last years of his business life. His operations expanded from tobacco to wheat, livestock, sheep, a mill, a fishery, a self-sustaining estate and more. After leaving office in 1797, Washington returned to Mount Vernon and, with the encouragement of his farm manager, James Anderson, entered the whiskey-distilling business. Though Washington lived only two years after leaving office, these two were his most profitable ever. In 1799, his distillery produced nearly 11,000 gallons of whiskey, making it the largest whiskey distillery in America at the time — yes, even bigger than Jacob “Jim” Beam’s.

Pragmatic Innovation. Washington was fascinated by new labor-saving technologies and made a lifetime commitment to practical experimentation. He kept regular correspondence with other thought leaders to keep on top of market changes, best practices and new technologies. He played a major role in developing America’s mule population and pioneered various agricultural methods. “He not only signed Patent No. 3,” notes Robert Shenk, senior vice president at George Washington's Mount Vernon, he “also installed the automated mill technology (as a licensee) into his Mount Vernon gristmill described in that patent.” At Mount Vernon’s flour mills, he paid dearly to import highly advanced French millstones whose carved milling surfaces could cut wheat and other grain with scissorlike precision. The resulting flour was fine, pure white and highly valuable. It would pass for what a modern baker would refer to as “cake flour.”

So what did it all mean? I have heard Dave Whorton, head of the Tugboat Institute, argue that the concept of running a business in an Evergreen way is revolutionary but not really new. It’s part of an old but enduring tradition that the world has forgotten how to celebrate. It was inspiring to consider Washington’s life as evidence that Dave is right.

Yes, Washington probably would have called Mount Vernon Evergreen. And maybe, one of our lecturers commented, his greatest Evergreen project was the United States itself.

Stephane Fitch is the CEO and Founder of FitchInk.

The Virtue Of The Four-Day Workweek

The greatest thing I ever did for my maternity apparel company, Ingrid & Isabel, was give my employees a four-day workweek.

I did this initially for myself, to create the kind of work-life balance I had always dreamed of having in a career. But it turned out to be just the right spark for corporate success.

Setting the dependable, realistic target of getting our work mostly done by Thursday evenings has inspired focus and efficiency without sacrificing deep thinking and creativity among my team. They feel accomplished, challenged and happy. And, best of all for my Evergreen business, it has created a culture where people work harder and smarter, and they are productive and stay with the company longer.

Before I launched Ingrid & Isabel in 2001, I spent most of my early career in advertising pulling all-nighters and flying from meeting to meeting. For a while, that was thrilling. I felt very important. But when I became pregnant with my first child (and couldn’t button my pants, leading to my Bellaband invention), my ambitions changed. Instead of the frantic pace of many businesses, I wanted to create an environment where everyone collaborated and worked together as a team in the most efficient way in four days so we could sign off and enjoy our weekends. I wanted to do more than give lip service to work-life balance. I wanted to empower my employees to succeed both at work and at home.

I remember pondering the creation of a company that had set days and expectations unlike a traditional company, and I ultimately settled on eliminating Fridays. From the beginning, my customers and vendors were informed that our offices were closed on Fridays. Because it’s the way we have always operated, we have found that our partners, big and small, respect our schedule. Of course, if there is a huge project or meeting that requires our appearance on a Friday, we cheerfully comply. But most of the time, our three-day weekends are left untouched. On average, most Ingrid & Isabel employees come in on Fridays a little less than once a month for only a couple of hours.

Just as we set a precedent with our clients and customers, I have done the same with our employees. For the most part, having a four-day workweek has been extremely beneficial for my company. The intensity and furious activity that propels us to get our work done by Thursday evening spurs our brains and makes us highly productive. Ingrid & Isabel has grown every year—it’s never stopped. Even during the recession, we were financially successful as it coincided with the launch of a less expensive line at Target, which only carries two maternity lines on the floor—one of which is ours. We are carried fleet-wide at Target, and we are the No. 1-selling maternity vendor for many of our retailers. The Bellaband (our signature item) is the No. 1-selling maternity accessory in the category.

There are some challenges that come with doing business this way—mostly around hiring and retaining employees. Because we offer a four-day workweek, we also offer a salary around 80 percent of market rate. Young, hungry candidates who want to earn as much as they can and move up quickly struggle with this concept. But for young workers, we offer more than just a short workweek. Because we are a small company, we expose them to the entire business process. We are constantly working on innovation and researching new products. In a workplace with greater upward mobility and a higher salary, young workers can be limited in what they can contribute because they are mostly serving the needs of other people. At Ingrid & Isabel, we embrace expansive thinkers who are just as comfortable rolling up their sleeves and tackling mundane tasks, like data collecting, for example, as they are being involved in top-level strategic, product and financial meetings. The work is broad and entrepreneurial.

So, we have to be upfront from the beginning about the salary, and we need to be honest about the fact that it’s expensive to live in a city like San Francisco. The hires that I find do the best with us are those at the manager and director level—and I have learned how to find the best personalities within those titles that could be a great fit at Ingrid & Isabel. These are people who care very much about what they do, have an innate curiosity about their work and enjoy witnessing their individual contributions when we implement new ideas and reach pregnant women in the best and most meaningful way. They tend to be less concerned with title and more interested in the value of what they do. They may be seeking better work-life balance, starting a family or just looking to take more vacations.

But at the other end of the spectrum, we don’t want people who think a four-day week means an easy ride. So, to weed out the candidates who might not be very productive Monday through Thursday—or who might need a larger, more structured work environment to meet productivity goals—we have a rigorous interview process. We have multiple people across functions interview each candidate, with me personally meeting each person, sometimes three times.

So, does it work? Well, Ingrid & Isabel’s revenue is up year over year in double digits percentagewise. I think we get better at what we do every year because we’re highly trained and motivated as a team to be productive. Just as we suggest smart—not excessive—shopping to pregnant mothers, we try to be smart about how we conduct our business. We do what’s important during a timeframe that makes sense; we create boundaries and expectations and deliver on them. Because of this, we have earned great respect in our industry.

Every other year, I ask my team if they want to go to a five-day workweek, which would come with a raise. Everyone, hands down, says no. And there you have it. It’s working for us and personally working for me. My three-day weekends are treasured.

I am thrilled to be part of the 14 percent of small companies who offer their employees a four-day week.

Ingrid Carney is founder and CEO of Ingrid & Isabel, the maternity clothing company behind the Bellaband.

The 116-Year-Old Evergreen Business

Choosing the Evergreen path can sometimes seem like a daunting challenge. Many entrepreneurs ask themselves: Can I build a business that will be profitable and grow strong without outside investors?

My company is proof that yes, you can. I am the third-generation owner of San Francisco-based McRoskey Mattress Co., which my grandfather cofounded in the late 19th century. Over 116 years, McRoskey has remained a private company dedicated to its people and paced growth.

My grandfather and his brother, and later my father and uncle, made the decision to create a quality product and maintain a steady course while doing so. They didn't follow trends unless there was a valuable reason to add a material or change the construction technique. To this day, we never do something new to save a nickel.

Staying Evergreen can be even more challenging when you operate in a city built on quickie IPOs. Over the years, outside investors have made inquiries, but I’ve avoided any such pursuit or discussion. The reason is simple: When I look at companies that are public, it seems to me it just puts up barriers between the manufacturer and the consumer. That is not what I want for our carefully cultivated company.

Instead of searching for investors, I focus on quality and customer service. I rely on a long-serving administrative and sales staff that customers have gotten to know and trust over the years. I have many employees who have helped several generations buy mattresses for their families.

In turn, our loyal customers are willing to pay a premium for the McRoskey brand. Prices, for instance, can be $2,100 for the Basic Twin set and $8,400 for the Natural California King set. We always look for customers who think sleep is important—and then try to intersect with them at the right moment. One big challenge these days is convincing new customers to look at McRoskey rather than stopping by a Sleep Train store or ordering a trendy Casper online. We do this by staying focused on building mattresses and box springs that provide enduring comfort.

There have been other challenges along the way. A 1998 fire damaged our San Francisco showroom. I managed to turn the disaster into an opportunity to renovate and update the space. Five years later another fire hit a showroom under construction in San Jose. We redirected merchandise to a newly opened showroom in Los Angeles. But after three years, I decided to close that store in order to fully focus on the Bay Area.

The 2008 financial crisis hit McRoskey Mattress Co. as hard as any fire as people opted to keep their old mattresses a little bit longer. Like many business owners during that time, I had to lay off some staff and reassess procedures. In the end, dealing with these tests was a healthy exercise.

Over the past three years, sales have been relatively flat. With the economy rebounding, I am now working hard to improve revenue. We have refreshed our brand to place more emphasis on the fact that we are the manufacturer. These changes are reflected in stores and online where customers can now purchase all of our bedding products.

When your business has been around for 116 years, I think it becomes—philosophically at least—a little easier to weather the cyclical ups and downs. Being the torchbearer for my family business keeps me on my toes, but I don’t feel oppressed by it. Even when there are pressures, I like to rise to the occasion.

I sleep very well at night.

Robin McRoskey Azevedo has been the CEO of McRoskey Mattress Co. since 1990. McRoskey Mattress Co., which first opened its doors in 1899, is headquartered in San Francisco.

Six Ways Evergreen Companies Can Attract Top Talent

“Why should I come work for you?”

If you’re a recruiter for a sexy Silicon Valley start-up that just landed millions of dollars in new funding, this is an easy question to answer. Outrageous perks like free dry cleaning, free gourmet lunches and sleep pods might seem, on the surface, more exciting to job seekers than the steady, paced and profitable growth an Evergreen company can boast.

Evergreen jobs offer a compelling, and safer, choice for many job seekers. But drawing in prospective employees can take a little more spin and creativity.

For the past six years, Carolyn Betts has been helping companies hire employees through Betts Recruiting, her San Francisco-based international talent-recruiting firm. When Betts and her team decided to make her company Evergreen, she shifted her own hiring habits. The pivotal question she says she asked herself was: “What makes an Evergreen company attractive to our current employees and to job seekers?”

The answer boils down to the unique culture every Evergreen company creates with its employees. The trick is making sure potential employees are aware of this culture—and that they’re weighting it just as heavily as they are the cafeteria offerings at the venture-funded start-up next door.

To entice people who would be drawn to the myriad benefits of working for an Evergreen company, Betts knew she had to promote and discuss her company in a different way than her public counterparts were talking about theirs. She came up with six ways for Evergreen recruiters to attract the best employees:

- Build—and promote—your employment brand: Betts says it’s important to both create a culture and make this culture widely known. “After the Tugboat Institute Summit, I looked up Balsam Brands,” Betts says. “They have an awesome website that is 100 percent focused on their culture.” Beyond creating a substantial website, get your employees talking online. Have them rave about the office culture on employee review sites like Glassdoor. You want potential employees to easily find out that your company is Evergreen and learn about the long-term cultural advantages that come along with that. Another popular way to boost your company’s appearance is to use social media. Instagram and Facebook are great platforms on which to display and share photos of the things that your company does to put its people first.

- Tell recruits during the interview process that you are Evergreen: Explain to potential hires what Evergreen is and what it means for your company. “When I tell people, they’re excited, because most people really do want to find a place where they can dedicate themselves to an important purpose for a long time,” says Betts. During an interview, she builds in some time to explain the difference between working for an Evergreen company and working for a venture-backed company. “In an Evergreen company, employees can expect a lot more loyalty from the owner and clear, simple objectives,” Betts says. “If an employee wants to be at a meaningful job with a purpose-driven team, he or she should consider Evergreen over an unpredictable and at times volatile ride at a venture-backed start-up that must grow big fast to satisfy the requirements of past and future exit-oriented funders.”

- Don’t just tell—show: Provide recruits with videos that show what life is like at your office. Even better, let them walk around your office and talk to current employees. Let them see your company’s culture in a transparent, up-close manner. “The frustration is trying to keep up with the Joneses,” Betts says. Recruits, especially in places like Silicon Valley, are used to walking into venture capital-funded businesses and being bombarded with free lunches, gym memberships and other such perks. Yet, offering perks is easy—building a culture of truly treating people well through thick and thin is not.

- Ask potential employees what they want: While this is a staple in any job interview, asking an employee what he or she wants out of a job over the long term is critical for an Evergreen recruiter. “This is how you find out if someone is focused on a short-term economic exit or aligned with your purpose and with the work and life benefits of a career in an Evergreen company,” Betts says. “This way you vet the people who are the right fit.”

- Hire for culture first: “One of the core values that our recruiting firm brings to the hiring process is finding not just the right person for the job but the right person for the company,” Betts says. A person is more than just his or her resume. Being able to integrate into a company and truly add value goes beyond having the right number of years of experience. It’s about having the same values, work ethic and goals as the rest of the company. A strong culture protects the company from people who prove not to be value aligned and rewards those who are.

- Strike while the iron is hot: “In today’s environment, move quickly for the right person,” Betts says. “But don’t shorten the interview process.” She says you can power through an interview process in a week, making sure all vital people on your team have a chance to meet or interview a recruit for fit. “You should be super excited about hiring this person, and that person should feel the same.”

Betts has one final tip for Evergreen CEOs who want to scale or build their businesses: When it comes to hiring everyone except your direct reports, “get the hell out of the way.” Allow your team to judge and make the hire. Of course you may want to meet the person. But never nix a recruit your entire team is voting for. “It’s your baby, your company—but you’re not going to love everyone walking in the door,” Betts says.

An Evergreen company has a lot of natural advantages in being purpose driven, profitably growing and putting people first for the long haul. When recruiting talent, it’s up to you to show job seekers that you’re the smart choice for a challenging, meaningful and successful career and life.