Partnering with Academia to Innovate and Grow

- Tim Dekker

- LimnoTech

Innovation is key to the growth and survival of any company. As an Evergreen® company that’s been in the continually changing field of environmental science for almost 50 years, we have a long history of innovation. Pragmatic innovation has been key to our survival and growth and is a core value that has been built into the processes and systems that define our organization. One thing that has been a little unique at LimnoTech throughout is the way we innovate through longstanding, purposeful partnerships with academia.

Our company started back in 1975 when environmental science was in its infancy, and when our founders at the University of Michigan were just figuring out how to match the brand-new capacity for numerical computing to the profound environmental problems we were seeing in the Great Lakes. Paul Freedman, a graduate student at the University of Michigan, saw the opportunity to create LimnoTech in collaboration with his research advisor Ray Canale, and ran the company for its first 47 years.

The spirit of research is built into Limno Tech’s DNA. We are an environmental science and engineering firm providing water-related services to clients throughout the United States and internationally. Our early partnership with the University of Michigan gave us a special opportunity to do important, innovative work. And since then, it has been a natural fit for our company to partner with academia whenever the opportunity arises. Our partnerships have resulted in many strategic advantages and have created some of our most exciting opportunities for growth, expansion, and meaningful work.

The University of Michigan partnership shaped our company during its formative years as we developed computer models to describe how natural systems like lakes and rivers worked, and as we proposed solutions to fix the problems created by environmental pollution. In those early days, the University was a continual source of new ideas and strategic hires. Over time we expanded the relationships to include other great schools: Notre Dame, Michigan Tech, the University at Buffalo, and even historic rivals like Ohio State. These days our partnerships are nationwide, including institutions all over the country and spanning many disciplines: science, engineering, design and planning, and the social sciences.

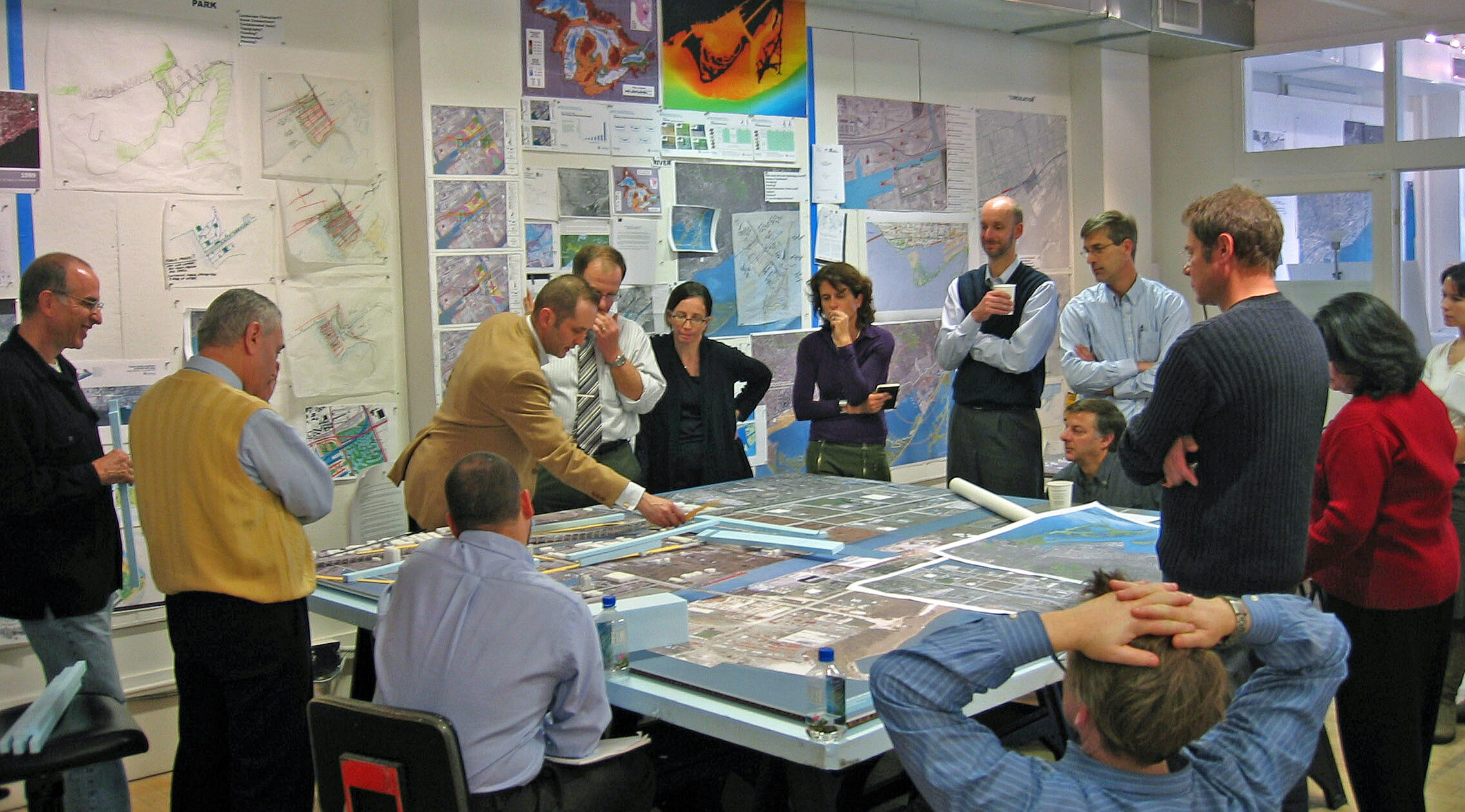

One example of our partnerships with academia today is our relationship with the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where I and others in our firm have served as lecturers and studio critics for more than a decade now. Our relationship with Harvard felt a little unconventional at the start; we’re mostly engineers and scientists, and Harvard’s design school has deep roots in the arts and teaches core design principles that felt very different from our normal ways of working.

One of our first experiences with Harvard had us in a design competition working with one of their most notable professors in Landscape Architecture, doing the core design and planning of a huge portion of the Toronto waterfront that included a massive river relocation and restoration process. It was an intimidating project, because in our experience such projects were usually led by engineers like us who do the hard technical planning work first, and figure out the human benefits later. Instead, our project was led by Michael Van Valkenburgh, a professor in practice at the Harvard GSD and leader of a growing design firm, MVVA, in New York City. Their approach to problem solving was very different from ours – creative, exploratory, interdisciplinary, and to my eyes, messy. It was very different from our previous work, which was cautious, linear, and grounded in scientific approaches. We were proud of our ability to solve complicated scientific problems, but the problems we were starting to see in our field were much more than that – complicated technically, but also financially, organizationally, socially, and politically. We needed better approaches for problem solving, and our new collaborators had them. Michael and his staff at MVVA were able to think about all the dimensions of a wicked problem at once. But delightfully, they needed us too – to provide clear answers to technical questions and hard boundaries for their proposed designs, and also to spark new ideas born in our years of technical experience.

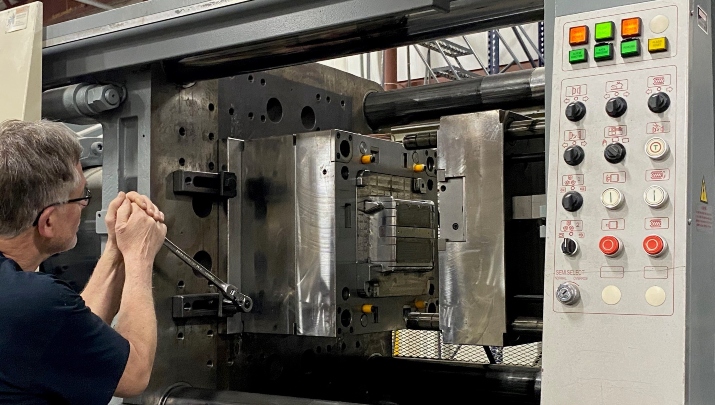

We made an explicit decision to learn from our new colleagues, and it completely changed the way we work. It wasn’t always easy – at times our staff was bewildered by requests to build accurate computer models based on design team models constructed out of cardboard and construction paper. The pace was also a shock – our new collaborators in landscape architecture generated new project ideas on a 24-hour cycle, and we had to adapt our capacity to build and apply computer models as fast as they could ideate. Spending time talking and working with these folks changed us, injecting LimnoTech with a level of creativity and an openness to viewing things in a different way that has made us so much better.

Thanks to our collaboration with them and the dual expertise we are able to bring to the table, we are now working on projects in Dallas, Tulsa, St. Louis, Toronto, Detroit, Buffalo, the Middle East, and Europe. The Don Lands design competition in Toronto turned into a billion-dollar project that’s now under construction, and it has been a game changer for our little company.

A second, powerful way that our relationship with Harvard has changed who we are and created opportunities for us is through their network. Harvard’s design program is influential, and most of the professors we have worked with there are professors-in-practice, teaching part-time and running their own firms. They are all connected through a strong, international network that extends to other schools like the University of Pennsylvania, Berkeley’s design school, and the University of Virginia. This network has led to dozens of creative engagements and enormous opportunities for our firm over the years.

A second example of academic collaboration takes us full circle back to the University of Michigan, but now engaging with a very different team of experts outside of our water science roots. A few years ago, an engineering professor and long-term collaborator, Dr. Peter Adriaens, became interested in how our understanding of water and its role in product supply chains could have implications for the performance and value of companies. This was a puzzle that others had tried to solve before without much success, and Peter guessed that this was mostly because of cultural differences: between the engineers who have access to water-related data and the financial analysts who know how to translate data into useful, actionable financial products. Peter deliberately bridged the cultural gap, securing a dual appointment with the University’s Ross School of Business and learning the language and technical tools familiar to the financial experts at Ross. He then combined this knowledge with the data and knowledge resources at LimnoTech to create a new financial product: waterBeta, a measure of stock price volatility that is specifically traceable to water risks. The waterBeta provides a way for portfolio managers to anticipate stock price performance benefit (alpha) from managing volatility in water risks during climate transitioning.

As an outcome of this collaboration with the University, LimnoTech and Dr. Adriaens created a new company, Equarius Risk Analytics, that is structured to provide water-related financial intelligence as a new set of products and services for companies and financial services providers. The company is pre-commercial but is an exciting example of the power of combining expertise and joining our efforts with researchers and thought leaders of all sorts.

The lessons we’ve learned through these experiences provide valuable insights for companies eager to embark on their own journey of collaboration. It might be true that academia is a more natural partner for us than for some other industries, but I believe that there is potential for all companies to benefit from such partnerships when the right opportunity arises. What might you gain from such an initiative?

First, working with academia allows you to leverage complementary strengths. Industry expertise coupled with academic research methodologies can lead to breakthrough technical innovations. Second, it might help you, as it has helped us, embrace multidisciplinary thinking. Collaborations can unlock new perspectives which can lead to innovative solutions that transcend traditional boundaries. Finally and importantly, these partnerships have allowed us to build and grow new networks and relationships. Universities are highly connected, and often to entirely different networks than your own.

The benefits go both ways, to us and to our academic partners, as our culture and network of professional contacts allows them to transform research into tangible impact. This can drive business growth for you and academic and societal progress for everyone. An openness to collaboration can cultivate your culture of pragmatic innovation and infuse fresh perspectives into your organization, and embracing new methodologies and approaches can catalyze transformative change.

More Articles and Videos

Fireside Chat with Dave Thrasher, Dan Thrasher, and Dave Whorton

- Dave Thrasher, Dan Thrasher, & Dave Whorton

- Supportworks and Thrasher Group

Get Evergreen insight and wisdom delivered to your inbox every week

By signing up, you understand and agree that we will store, process and manage your personal information according to our Privacy Policy