Passion Drives Industry-Changing Innovation

- Pete Catoe

- ECRS

Even if you don’t own one, I imagine you are familiar with the KitchenAid mixer. It is a beautiful product: sleek, durable, made from highly recyclable materials, and built to last for a long, long time. I have had mine for about 35 years. Although I am CEO of ECRS, a company that specializes in retail automation for grocery store technology, such as point of sale, self-checkout, inventory, and supply chain, as well as the software that runs on a deli scale, one of our most important innovations in recent years was inspired by this product outside our industry – the KitchenAid mixer.

As an Evergreen® company, we are dedicated to Pragmatic Innovation and are always looking for opportunities to do what we do better. In this case, as is often true, innovation began with a seed of dissatisfaction, a spark that ignites a desire for change. I saw room for improvement, both in quality and sustainability, in the industry standard with which we had been working for years. Thus began the story of our AutoScale™ Max.

The most common point of sale products for grocery stores, whether they contain scales or not, are made from plastic. The standard labels have a backing to them because they must be adhesive, which means they produce a significant amount of waste. The standard scales we have used for ages, which we’ve typically bought from partners in China, are therefore able to hold a roll that will last maybe three days. They tend to run out when you are at your busiest, and it’s a pain to change them. For a long time, this was our reality; we bought the scales from China, loaded our software on them, and sold them to our customers. But I knew we could do better, and I found myself thinking about that KitchenAid mixer. I wanted something to match that in design, elegance, quality, and capacity.

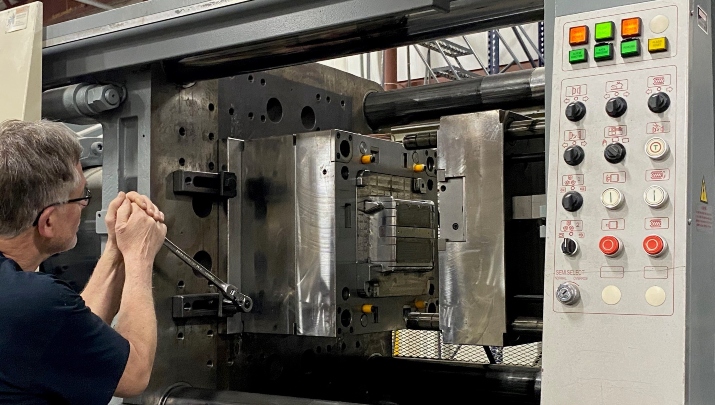

As I started to imagine the product I wanted to build—one that would be the KitchenAid of scales—I knew a few things had to change from the norm. I wanted to build it to last, and it seemed that building it out of metal rather than plastic was the best bet. I also didn’t see why we couldn’t design something that could hold a bigger roll of labels. Not just a little bigger, but much bigger. Working with partners, we found a special label that didn’t require backing, so we were able to increase efficiency and reduce waste that way, but why couldn’t the roll in the scale be twice as big as the normal ones? Or bigger? I set the goal to develop something that could hold a roll of labels that was ten inches thick. That would represent an 11x increase in length and a very significant time savings for customers.

I was fixated on creating something excellent and I was willing to do whatever it took not just to build a product, but to revolutionize it. Design, functionality, and sustainability drove our team’s quest, but our path was not without hurdles. Initially, we engaged a design firm whose work was terrible, and ultimately resulted in setbacks. The first prototype they created that could contain the ten-inch roll was much larger than competing scales, which was not the point at all. That phase of the project was frustrating and caused us to lose quite a bit of money. If I hadn’t been driven by such an intense passion to succeed, we might have given up. But we didn’t.

As we regrouped after the first failed design attempt, we happened to discover a local designer right here in my hometown of Boone, North Carolina. In terms of his experience and skills, he was younger with much less experience than our original design partner, but something stuck out to me: his passion. He seemed as excited as we were by the project, and thanks to our shared enthusiasm and expertise, we started to gain momentum.

One of the keys to our eventual success was the fact that our new design team had the brilliant idea to incorporate the Microsoft Surface Tablet into our new design. It is embedded into the scale and it’s extremely fast and powerful. Because of this integration, we tapped into Microsoft’s supply chain, and because they are making millions of these, the cost came down – something we had not necessarily expected. In the end, we managed to produce a gorgeous looking piece of equipment that is built like a KitchenAid mixer. It fits seamlessly into a deli, holds a ten-inch roll of labels, and is faster and more powerful than anything else out there—and built more cost-effectively by developing it with our own in-house team!

Once we innovated the machine itself, we were able to simply insert the software we had already developed into it. The software in the AutoScale Max is almost identical to the software we used in our other machines, meaning we hardly had to spend any money on the coding side of the innovation. Before the AutoScale Max, we mostly sold point of sale software, which is extremely similar to the scale software. Now, we can sell products for point of sale and scales. If a customer, for example, has ten point of sale lanes, we can sell them products for all ten and we can also sell them the ten scales they need. We just doubled our sales! That fact, combined with the lower cost of the new machine, has resulted in savings for our customers, increased sales, and thus increased revenue for ECRS to reinvest in more innovative solutions that continually serve our customers.

As an additional outcome of all this, this innovation has significantly reduced our dependence on China. This was not necessarily one of our initial goals, but because of increasing concerns over supply chain vulnerabilities and ethical considerations, this turned out to be an added bonus. Our relationship with our Chinese suppliers was not problematic, but it was primarily driven by concerns of cost, convenience, and efficiency above all else. With this innovation, we find that we can maximize all of these, and at the same time, bring production right back here to home.

What is the lesson here? What drove this innovation process? First, when I look back at the road we travelled from the idea to the finished product, I realize that it would not have happened without my own almost obsessive passion for it. And the fact that our second designer shared that same passion was key. The rest, honestly, was just great problem solving. The integration of the Microsoft Tablet was fortuitous, but that is just another example of hitting a roadblock and looking around for a creative way to overcome it. The answers often lie in unexpected places and are not always as hard as you think they’ll be. It’s funny how passion can drive a team to make hard things easy.

More Articles and Videos

Fireside Chat with Dave Thrasher, Dan Thrasher, and Dave Whorton

- Dave Thrasher, Dan Thrasher, & Dave Whorton

- Supportworks and Thrasher Group

Get Evergreen insight and wisdom delivered to your inbox every week

By signing up, you understand and agree that we will store, process and manage your personal information according to our Privacy Policy